Megan McArdle has a piece for Bloomberg that really resonates with me. She starts out with something that I’ve always felt as well:

I care a lot about the absolute condition of the poor…but I don’t care whether Bill Gates is living in a house that cost 19 squintillion dollars. I care whether everyone else in the country has a warm, dry abode with indoor plumbing and all the other mod cons.

But she then goes on to talk about a kind of inequality that really does matter: marriage inequality. Not the kind that’s abut sexuality, but rather the kind that’s about class.

Marriage has basically followed the same path as income over the last 50 years. The college-educated have it better than ever — they are enjoying what Harvard researcher Kathryn Edin calls “superrelationships,” characterized by extremely high levels of rapport, cooperation and satisfaction. The bottom two thirds, on the other hand, are in unstable relationships that tend to break apart under stress. They typically have at least one child before they marry, experts told me, and when they do marry, it’s not to the father of their child. This is bad for the people in these relationships, and for the children they produce.

What strikes me as crucial about this perspective is the recognition that poverty, at least in the First World, is not primarily about money. It’s first and foremost a social issue, and only secondarily an economic issue. Given stable family environments, people will move up the income ladder. The problem is not primarily about the upper class stealing resources or oppressing lower classes, but about poverty traps that keep lower classes mired in self-destructive cycles. It’s also important to realize that the upper classes contribute to this cycle, if only in terms of impressions, by preaching other than what they practice.

Conservatives have called for elites to lead on the issue — to speak out for the values that they actually practice (marriage before children, fidelity, heavy investment in family), rather than a more libertine set of values that they claim to believe (there are lots of good ways to raise children, and we shouldn’t judge).

I’m not sure if this is actionable or not-McArdle doesn’t seem to think that it is-but I still think it’s worth noting. There was one other point McArdle mentioned that I found really illuminating:

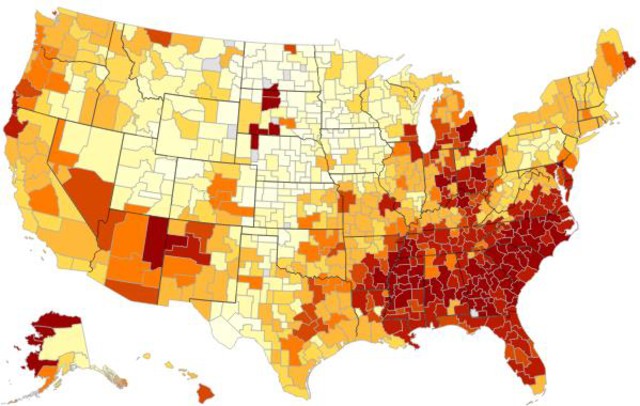

Here’s something interesting that didn’t predict mobility: the share of income enjoyed by the top 1 percent. Scott Winship of the Brookings Institution pointed out that inequality does seem to be correlated with lower income mobility across countries, so it’s very interesting indeed that the share of income held by the very top doesn’t predict inequality within the U.S. But Chetty hastened to point out that this doesn’t mean that inequality doesn’t matter. In fact, inequality is inversely correlated with mobility — the higher inequality is, the lower the chances that a child born in the bottom will end up in the top. But the problem is not the top incomes; it’s the distance between the 25th percentile, and the 75th. “So, our takeaway,” said Chetty, “is that it seems to be something that’s related to the extent of which the middle class exists and is pulling away from the poor rather than upper tail extreme concentration of wealth.”

This strongly correlates with the idea (discussed here previously) that the middle class is not dying and that the ultra-wealthy are not (intrinsically) the problem. The problem is a fracturing of society that is evident not at the extremes, but closer to the middle, where the functional and dysfunctional sides of America are slowly pulling apart. The more the classes segregate, the more pronounced their respective trends will be: those locked in dysfunctional cycles will remain even more trapped because the vital exposure to other alternatives will be increasingly rare. And the functional halves will continue a kind of solipsistic journey into materialistic consumerism that threatens their humanity in more subtle ways.

If there’s one thing I like about this right-leaning perspective on inequality, other than the practical benefits, it’s an understanding that income equality is a horrifically impoverished shadow of the larger possible visions of equality.

Endorse your last line 1,00%!

But Megan misses several forests for an anecdote about her grandparents and an outlying tree in the city of SLC.

Firstly, maybe Megan comes from several generation of entrenched poverty and it was just good luck that her grandparents’ parents managed to bootstrap their way out of this oppression so that their children had a place to live for six year during The Depression. Consider, though, that everyone had it rough and having a house to live in, rent free, meant they were probably relatively well off! This is especially true when you consider they were, nominally, afforded access to basic financial instruments that others wouldn’t gain access to for another 50 years. Also, her grandparents probably didn’t experience any wage theft, redlining, etc.

Anyway…

Here are the top 10 of the 50 biggest cities for the mobility measure she’s highlighting:

1-Salt Lake City, UT: 11.5%

2-San Jose, CA: 11.2%

3-San Francisco, CA: 11.2%

4-Seattle, WA: 10.4%

5-San Diego, CA: 10.4%

6-Pittsburgh, PA: 10.3%

7-Sacramento, CA: 10.3%

8-Manchester, NH: 9.9%

9-Boston, MA: 9.8%

10-New York, NY: 9.7%

http://www.equality-of-opportunity.org/

One of these things is not like the other:

http://www.flickr.com/photos/walkingsf/5011039992/in/set-72157624812674967

We know that ethnic nepotism affects economic collaboration, whether that collaboration involves quasi-willful tithing or compulsory transfers via tax collection. SLC, then, is a problematic case to champion in that its charity-based redistributionist policies fit a city that, ethnically, is a lot closer to a Scandinavian country than it is to the communities in which a huge majority of Americans live.

Here are the top 30 of the 100 largest commuting zones for that same measure:

Bakersfield, California

Santa Barbara, California

Salt Lake City, Utah

San Francisco, California

San Jose, California

Scranton, Pennsylvania

Des Moines, Iowa

Toms River, New Jersey

San Diego, California

Seattle, Washington

Santa Rosa, California

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Madison, Wisconsin

Reading, Pennsylvania

Modesto, California

Honolulu, Hawaii

Sacramento, California

Brownsville, Texas

Manchester, New Hampshire

Boston, Massachusetts

New York, New York

Los Angeles, California

Spokane, Washington

Allentown, Pennsylvania

Washington DC

http://www.equality-of-opportunity.org/index.php/city-rankings/city-rankings-100

Compare to the top 30 MSAs:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Metropolitan_Statistical_Areas

See what’s missing? Perhaps there’s some public policy that can help scale the SLC model to the rest of the country (if not to a city like Atlanta). But I’m not sure there’s really any good evidence that this is possible.

Well, y’all could convert to Mormonism….

Honestly, that would be a pretty efficient solution.

Nice companion piece: http://www.aei-ideas.org/2013/07/income-mobility-study-shows-the-value-of-families-schools-and-innovation/

Another on commutes: http://www.aei-ideas.org/2013/07/the-role-of-long-commute-times-in-raising-unemployment/

And another on shale oil: http://www.aei-ideas.org/2013/07/add-the-highest-level-of-income-mobility-in-the-country-to-the-long-list-of-benefits-resulting-from-shale-oil-in-the-bakken/