“Is Poland’s government right-wing or left-wing?” asks a recent article in The Economist.

Its leaders revere the Catholic church, vow to protect Poles from terrorism by not accepting any Muslim refugees and fulminate against “gender ideology” (by which they mean the notion that men can become women or marry other men).

Yet the ruling Law and Justice party also rails against banks and foreign-owned businesses, and wants to cut the retirement age despite a rapidly ageing population. It offers budget-busting handouts to parents who have more than one child. These will partly be paid for with a tax on big supermarkets, which it insists will somehow not raise the price of groceries.

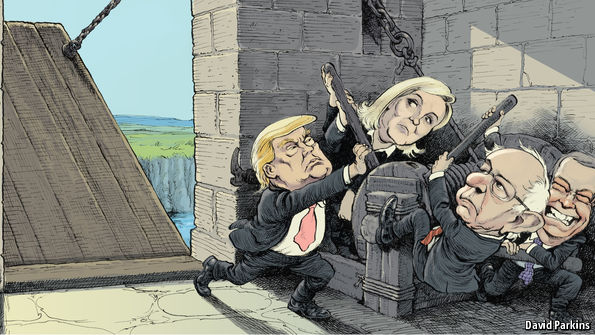

This represents a new kind of political divide; one that is “less and less between left and right, and more and more between open and closed. Debates between tax-cutting conservatives and free-spending social democrats have not gone away. But issues that cross traditional party lines have grown more potent. Welcome immigrants or keep them out? Open up to foreign trade or protect domestic industries? Embrace cultural change, or resist it?” As the British head of YouGov noted, the political ideologies are either “drawbridge up” or “drawbridge down.” The American context of all this is particularly depressing:

In America the traditional party of free trade and a strong global role for the armed forces has just nominated as its standard-bearer a man who talks of scrapping trade deals and dishonouring alliances. “Americanism, not globalism, will be our credo,” says Donald Trump. On trade, he is close to his supposed polar opposite, Bernie Sanders, the cranky leftist who narrowly lost the Democratic nomination to Hillary Clinton. And Mrs Clinton, though the most drawbridge-down major-party candidate left standing, has moved towards the Trump/Sanders position on trade by disavowing deals she once supported.

The two main forces driving the “drawbridge up” view “are economic dislocation and demographic change.” In turns out that “many mid- and less-skilled workers in rich countries feel hard-pressed. Among voters who backed Brexit, the share who think life is worse now than 30 years ago was 16 percentage points greater that the share who think it is better; Remainers disagreed by a margin of 46 points. A whopping 69% of Americans think their country is on the wrong track, according to RealClearPolitics; only 23% think it is on the right one.” It’s also true that

Rich countries today are the least fertile societies ever to have existed. In 33 of the 35 OECD nations, too few babies are born to maintain a stable population. As the native-born age, and their numbers shrink, immigrants from poorer places move in to pick strawberries, write software and empty bedpans. Large-scale immigration has brought cultural change that some natives welcome—ethnic food, vibrant city centres—but which others find unsettling. They are especially likely to object if the character of their community changes very rapidly.

This does not make them racist. As Jonathan Haidt points out in the American Interest, a quarterly review, patriots “think their country and its culture are unique and worth preserving”. Some think their country is superior to all others, but most love it for the same reason that people love their spouse: “because she or he is yours”. He argues that immigration tends not to provoke social discord if it is modest in scale, or if immigrants assimilate quickly.

There is an optimistic side to all this:

Although the drawbridge-uppers have all the momentum, time is not on their side. Young voters, who tend to be better educated than their elders, have more open attitudes. A poll in Britain found that 73% of voters aged 18-24 wanted to remain in the EU; only 40% of those over 65 did. Millennials nearly everywhere are more open than their parents on everything from trade and immigration to personal and moral behaviour. Bobby Duffy of Ipsos MORI, a pollster, predicts that their attitudes will live on as they grow older.

As young people flock to cities to find jobs, they are growing up used to heterogeneity. If the Brexit vote were held in ten years’ time the Remainers would easily win. And a candidate like Mr Trump would struggle in, say, 2024.

But in the meantime, the drawbridge-raisers can do great harm. The consensus that trade makes the world richer; the tolerance that lets millions move in search of opportunities; the ideal that people of different hues and faiths can get along—all are under threat. A world of national fortresses will be poorer and gloomier.

1 thought on “Raising the Drawbridges”

Comments are closed.