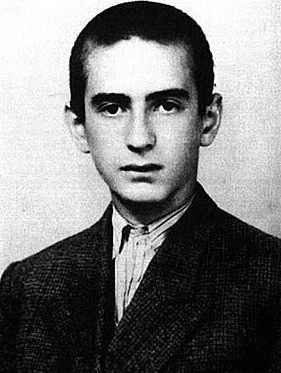

Elie Wiesel departed this world at the age of eighty seven. He has had a tremendous influence on my life, though I never met or corresponded with him. His books were always in the house when I was growing up, and I remember my mother retelling for me the plot of Dawn, but I cannot remember how old I was. Perhaps I was nine. The details have faded but the memory remains and comes to mind quite often. Honestly, it was sobering and a bit frightening to realize that no one is exempt from life’s horrors, that even I might be forced at some point to choose between two ugly outcomes. I still hope that I never will, but it was Elie Wiesel who forced me to acknowledge the possibility that it could happen.

Elie Wiesel departed this world at the age of eighty seven. He has had a tremendous influence on my life, though I never met or corresponded with him. His books were always in the house when I was growing up, and I remember my mother retelling for me the plot of Dawn, but I cannot remember how old I was. Perhaps I was nine. The details have faded but the memory remains and comes to mind quite often. Honestly, it was sobering and a bit frightening to realize that no one is exempt from life’s horrors, that even I might be forced at some point to choose between two ugly outcomes. I still hope that I never will, but it was Elie Wiesel who forced me to acknowledge the possibility that it could happen.

I have not rushed to post on Wiesel’s death because I have been picking up his works again and pondering his life. He deserves as much. I confess that it has been at least a year since I last read something of his. Wiesel himself resisted tidy conclusions. Still, something that I have noticed while following media coverage is just how much is misunderstood about Wiesel. He had his flaws and failings, of course, and valid criticisms can (or is it should) be leveled at him. There were even survivors with more compelling views on the universality of the Holocaust than his own, and Wiesel sometimes clashed with them, but he was a powerful voice for good nonetheless. Then there was the disgraceful spectacle of people like Max Blumenthal, who possess the moral stature of a Chihuahua, publishing tweet after tweet vilifying Wiesel not long after his death was announced.

Something that I can see even in many valid criticisms is that Wiesel is being judged by our own image of a Holocaust survivor and champion of human rights should be rather than by what Wiesel actually was. To understand Wiesel we must set aside such grand images as citizen of the world and its conscience, and start with the Elie Wiesel who was deported to the kingdom of night, as he would put it. A shy but ardent Hasidic youth who viewed everything through a spiritual lens. His parents had to force him to set some time aside for secular studies, such was his religious fervor. Then came the Holocaust, an outburst of the forces of evil so intense that it destroyed his ability to believe as he once did. Wiesel always wanted to recover that simple faith, but could not. This is the thread running throughout his works, the source of the enigmatic laughter and silences that fill his stories.

Night is a powerful novel. Really needs no introduction. Dawn is not as well known, but as noted above, perhaps more compelling and troubling because it deals with the internal struggle of a Holocaust survivor faced with making an awful choice. If Night is about surviving in a kingdom where God does not act, Dawn looks at the choices one must make when acting in history instead of God. Night will make you weep, and Dawn will chill you, but if you want to get at the man behind Wiesel’s public persona then read Souls on Fire. Souls is a collection of sayings, stories, and character sketches of several 18th-19th century Hasidic masters, leaders of a Jewish revivalist movement in Eastern Europe. Wiesel has written quite a bit on this or that Hasidic master. It is a prominent topic in his writings, and though I have never bothered to quantify this, I would not be surprised if he has written more frequently and directly about Hasidism than he has about the Holocaust, but everything that he wrote eventually touched upon his experience in the camps.

The Hasidic master, or Rebbe, acts as bridge between his followers, the Hasidim, and God. The Rebbe was central to how they approached the world, so telling stories about these masters practically became a sacred duty. These were stories about hidden saints and holy beggars, miracles and prophecies, uplifting the poor and downtrodden, intense longing for the Messiah as if he were due any minute, putting God on trial for neglecting his children, and a host of other colorful episodes, but most of all about the soul and how to mend it. Sometimes cryptic and paradoxical, they all share a love of truth. These stories were used to draw man closer to God rather than simply entertain. Wiesel did that, too. “I don’t believe the aim of literature is to entertain, to distract, to amuse.”

Hasidism, then, was the world of Wiesel’s innocence, where God was close, always ready to intervene on behalf of those who loved him, a world filled with warm memories of conversations with his grandfather the devout Hasid. It was he who taught Wiesel his first stories and embodied their virtues. Hasidism was about faith. Not mental affirmation, but an attitude of trust and devotion.

In the chapter entitled Disciples IV, Elie Wiesel relates a Hasidic legend of how Satan protested the birth of a particular Rebbe so holy that he would draw enough followers closer to God so as to destroy Satan’s kingdom effortlessly. The heavenly court recognized the unfairness of that scenario, and decided to send a rival – a counterfeit Rebbe – whom no one would suspect of serving God’s rival.

How is one to know? How does one recognize purity in a man? And how can one be sure? I remember putting this question to my grandfather. He chuckled and his eyes twinkled when he answered: “But one is never sure; nor should one be. Actually, it all depends on the Hasid; it is he who, in the final analysis, must justify the Rebbe.”

It is hard not to see this as really being about God, about Wiesel’s relationship with him. This answer to a childhood question, I think, lies behind the anger in Night, and behind the moral calculus in Dawn. Like the old chestnut, show me your friends and I will show you who you are. With Wiesel, though, there is never a simple affirmation of man’s moral superiority to God. That is a subtle nuance which even as fine a film as God on Trial (inspired by a Wiesel experience and story) misses. Man is responsible for affirming his devotion to truth through his actions and choices, perhaps even to transform his master through them. His failure to do so can have acute repercussions because God and man are inseparably linked.

“You’ll grow up, you’ll see,” my grandfather had said. “You’ll see that is more difficult, more rare to find a Hasid than a Rebbe. To induce others to believe is easier than to believe…”

Another story is shared of a Rebbe scolding God for keeping an old man like him waiting all his life for the messiah, then Wiesel’s own memory of his grandfather blessing him to see the messiah end evil, and how that caused him to tremble in Auschwitz for his grandfather. A story about a holy dance invites Wiesel to wonder how his grandfather died. For him, it is all connected. He expressed what he experienced in the camps in terms of these Hasidic tales and sayings.

One of Hasidism’s finest tales relates that the founder of Hasidism went to a certain spot in the woods to perform a ritual and utter a prayer to avert a disaster. His successor could not remember the ritual, but knew the spot and the prayer. The next Rebbe knows only the spot, and, finally, only the story remains. This must suffice, or can it? Wiesel suggests that we might be past that stage.

The proof is that the threat has not been averted. Perhaps we are no longer able to tell the story. Could all of us be guilty? Even the survivors? Especially the survivors?

That last question alone opens up a world of anguish that the trite and easy phrase survivor’s guilt can never fathom. It also lends urgency to the task of storytelling. There are no easy answers to any of these questions which occupied Wiesel his entire life.

Two sayings of Hasidic masters are given in the chapter with no commentary. “To pronounce useless words is to commit murder,” and, “Nothing and nobody down here frightens me… But the moaning of a beggar makes me shudder.” Both of these encapsulate Wiesel’s approach as author and witness. Waste no word on things that do not teach truth and fear nothing as much as another’s suffering.

There is much more that could be discussed. Instead, read Souls on Fire, especially the moving postscript describing why he wrote it. Your time will be greatly rewarded.

To end like I began, on a personal note: I was surprised to feel no sorrow at Wiesel’s passing. In fact, I almost felt happy. I typically get very emotional thinking about the Holocaust at any length. Why not now? In Jewish thought death is often considered a passage from the world of illusion to the world of truth. Wiesel loved truth but was haunted by it. He was truly a soul on fire, so perhaps now he will be able to see things as they really are, and meet with God to reconcile differences and finally have his questions answered. A chance, I feel, to regain his childhood faith.