A couple years ago, I wrote,

Other studies show that an increased minimum wage causes firms to incrementally move toward automation. Now, this too could be seen as a trade-off: automation and technological progress tend to make processes more efficient and therefore increase productivity (and eventually wages), raising living standards for consumers (which include the poor). Nonetheless, the point is that while unemployment in the short-term may be insignificant, the long-term effects could be much bigger. For example, one study finds that minimum wage hikes lead to lower rates of job growth: about 0.05 percentage points a year. That’s not much in a single year, but it accumulates over time and largely impacts the young and uneducated.

A couple new studies this year demonstrate the link between minimum wage hikes, automation, and job loss. As reported from AEI’s James Pethokoukis,

Now comes the new NBER working paper, “People Versus Machines: The Impact of Minimum Wages on Automatable Jobs” by Grace Lordan and David Neumark (bold is mine):

“Based on CPS data from 1980-2015, we find that increasing the minimum wage decreases significantly the share of automatable employment held by low-skilled workers. The average effects mask significant heterogeneity by industry and demographic group. For example, one striking result is that the share in automatable employment declines most sharply for older workers. An analysis of individual transitions from employment to unemployment (or to employment in a different occupation) leads to similar overall conclusions, and also some evidence of adverse effects for older workers in particular industries. … Our work suggests that sharp minimum wage increases in the United States in coming years will shape the types of jobs held by low-skilled workers, and create employment challenges for some of them. … Therefore, it is important to acknowledge that increases in minimum wage will give incentives for firm to adopt new technologies that replace workers earlier. While these adoptions undoubtedly lead to some new jobs, there are workers who will be displaced that do not have the skills to do the new tasks. Our paper has identified workers whose vulnerability to being replaced by machines has been amplified by minimum wage increases. Such effects may spread to more workers in the future.”

Three things: First this study is a great companion piece to a recent one by Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo analyzing the effect of increased industrial robot usage between 1990 and 2007 on US local labor markets: “According to our estimates, one more robot per thousand workers reduces the employment to population ratio by about 0.18-0.34 percentage points and wages by 0.25-0.5 percent.”

Second, Lordan and Neumark note that minimum wage literature often, in effect, ends up focusing on teenager employment as it presents aggregate results. But that approach “masks” bigger adverse impacts on some subgroups like older workers who are “more likely to be major contributors to their families’ incomes.” This seems like an important point.

Third, some policy folks argue that it’s a feature not a bug that a higher minimum wage will nudge firms to adopt labor-saving automation. (Thought not those arguing for robot taxes.) The result would be higher productivity and economic growth. But perhaps we are “getting too much of the wrong kind of innovation.”

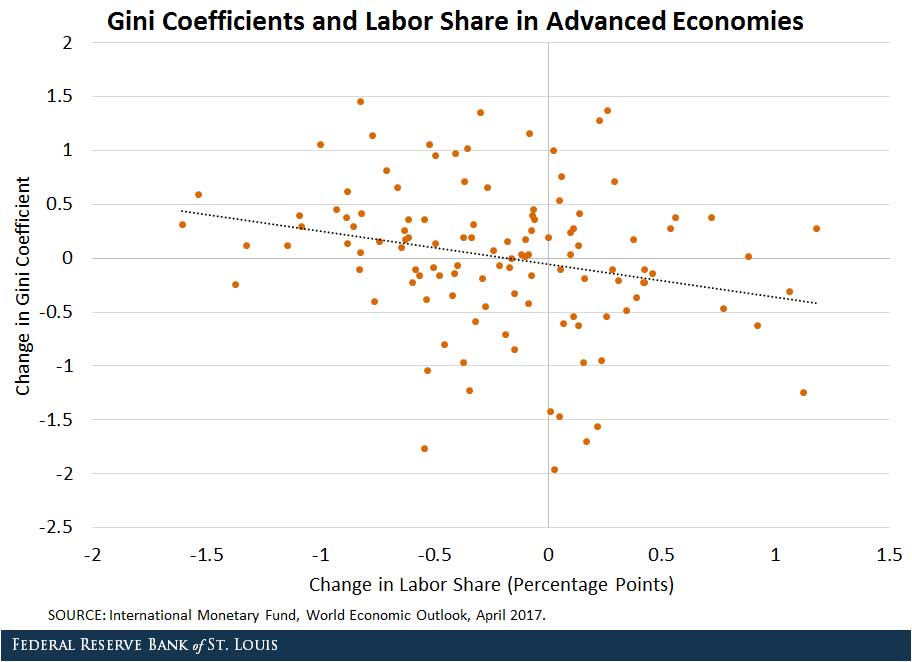

As the St. Louis Fed explains, “labor share declined 3.3 percentage points in advanced economies from 1980 to 2015”:

One of the explanations for the decline of the labor share has been an increase in productivity that has outpaced an increase in real wages, with several studies attributing half the decline to this trend.

This increase in productivity has been driven by technological progress, as manifested in a decline in the relative price of investment (that is, the price of investment relative to the price of consumption). As the relative price of investment decreases, the cost of capital goes down, and firms have an incentive to substitute capital for labor. As a result, the labor share declines.

The decline in the labor share that results from a decline in the relative price of investment has contributed to an increase in inequality: A decrease in the cost of capital tends to induce automation in routine tasks, such as bookkeeping, clerical work, and repetitive production and monitoring activities. These are tasks performed mainly by middle-skill workers.

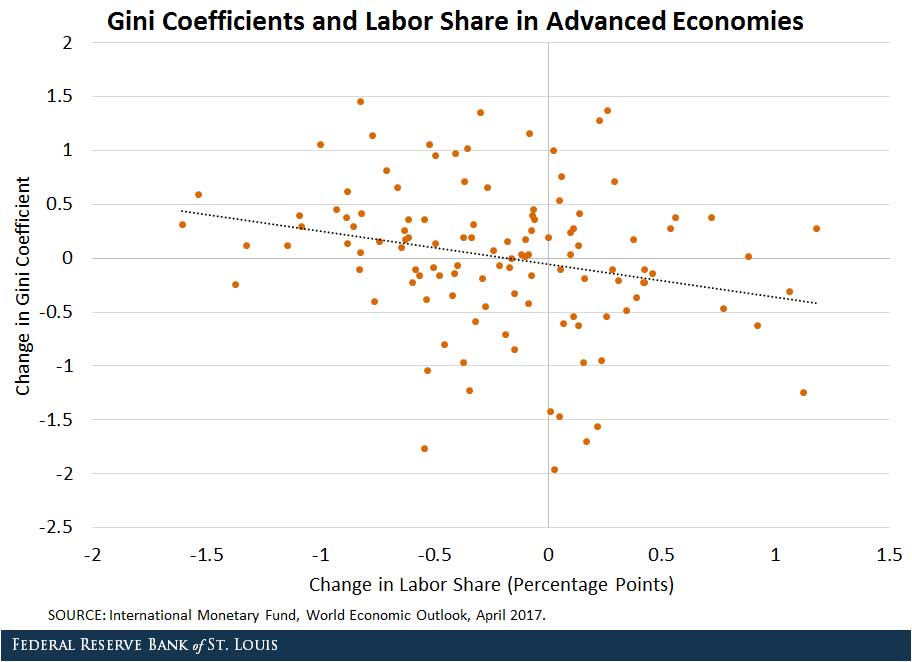

Hence, these are the segments of the population that are more affected by a reduction in the relative price of investment. The figure below displays the correlation between changes in the advanced economies’ labor share and their Gini coefficients (which measure income inequality).

The Fed concludes,

Technological progress promotes economic growth, but as the findings above suggest, it can also reduce the welfare of a large part of the working population and eventually have a negative effect on economic growth.

An important role for policymakers would be to smooth the transition when more jobs are taken over by the de-routinization process. At the end of the day, technology should relieve people from performing repetitive tasks and increase the utility of our everyday lives.