In April, I wrote about a new 10-year experiment testing a universal basic income in Kenya. While I find arguments for UBI compelling (especially those made by Matt Zwolinski), it is worth looking what experts are saying about it. Charles Murray has argued that for the UBI to work, it must replace all other transfer systems and bureaucracies. But economists are not so sure.

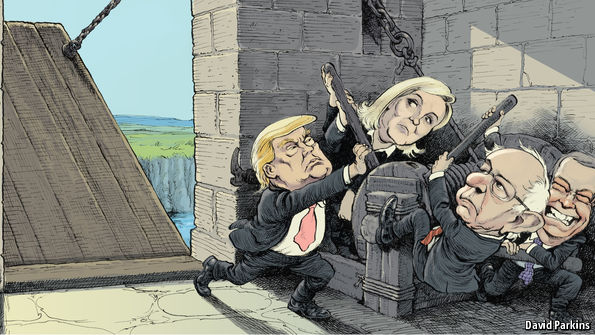

Granted, this is mainly a response to Murray’s particular brand of UBI. But are there other reasons to be skeptical of UBI? Let’s consider the costs. The Economist reports,

An economy as rich as America’s could afford to pay citizens a basic income worth about $10,000 a year if it began collecting about as much tax as a share of GDP as Germany (35%, as opposed to the current 26%) and replaced all other welfare programmes (including Social Security, or pensions, but not including health care) with the basic-income payment.

Such a big jump in the size of the state should make anyone wary. Even if levied efficiently, on an immovable asset like land, tax rises on this scale would have unpredictable effects on growth and wealth creation. Yet an income of $10,000 is still extremely low: it would leave many poorer people, such as those who rely on the state pension, worse off than they are now—at the same time as billionaires started getting more money from the state.

A universal basic income would also destroy the conditionality on which modern welfare states are built. During an experiment with a basic-income-like programme in Manitoba, Canada, most people continued to work. But over time, the stigma against leaving the workforce would surely erode: large segments of society could drift into an alienated idleness. Tensions between those who continue to work and pay taxes and those opting out weaken the current system; under a basic income, they could rip the welfare state apart.

Lastly, a basic income would make it almost impossible for countries to have open borders. The right to an income would encourage rich-world governments either to shut the doors to immigrants, or to create second-class citizenries without access to state support.

The Brookings Institution’s Isabel Sawhill lists two major objections to a UBI:

- “Robert Greenstein argues…that a UBI would actually hurt the poor by reallocating support up the income scale. His logic is inescapable: either we have to spend additional trillions providing income grants to all Americans or we have to limit assistance to those who need it most.”

- “Liberals have been less willing to openly acknowledge that a little paternalism in social policy may not be such a bad thing. In fact, progressives and libertarians alike are loath to admit that many of the poor and jobless are lacking more than just cash. They may be addicted to drugs or alcohol, suffer from mental health issues, have criminal records, or have difficulty functioning in a complex society. Money may be needed but money by itself does not cure such ills.”

She instead suggests the possibility of “unconditional payments along the lines of a UBI, but to phase it out as income rises.” But more fundamentally, she notes that “the biggest problem with a universal basic income may not be its costs or its distributive implications, but the flawed assumption that money cures all ills.”

As we wrestle over the best policy to assist the poor and needy, we must be willing to look at it from all angles.

Psychologists generally define forgiveness as a conscious, deliberate decision to release feelings of resentment or vengeance toward a person or group who has harmed you, regardless of whether they actually deserve your forgiveness. Just as important as defining what forgiveness is, though, is understanding what forgiveness is not. Experts who study or teach forgiveness make clear that when you forgive, you do not gloss over or deny the seriousness of an offense against you. Forgiveness does not mean forgetting, nor does it mean condoning or excusing offenses. Though forgiveness can help repair a damaged relationship, it doesn’t obligate you to reconcile with the person who harmed you, or release them from legal accountability. Instead, forgiveness brings the forgiver peace of mind and frees him or her from corrosive anger. While there is some debate over whether true forgiveness requires positive feelings toward the offender, experts agree that it at least involves letting go of deeply held negative feelings. In that way, it empowers you to recognize the pain you suffered without letting that pain define you, enabling you to heal and move on with your life.

Psychologists generally define forgiveness as a conscious, deliberate decision to release feelings of resentment or vengeance toward a person or group who has harmed you, regardless of whether they actually deserve your forgiveness. Just as important as defining what forgiveness is, though, is understanding what forgiveness is not. Experts who study or teach forgiveness make clear that when you forgive, you do not gloss over or deny the seriousness of an offense against you. Forgiveness does not mean forgetting, nor does it mean condoning or excusing offenses. Though forgiveness can help repair a damaged relationship, it doesn’t obligate you to reconcile with the person who harmed you, or release them from legal accountability. Instead, forgiveness brings the forgiver peace of mind and frees him or her from corrosive anger. While there is some debate over whether true forgiveness requires positive feelings toward the offender, experts agree that it at least involves letting go of deeply held negative feelings. In that way, it empowers you to recognize the pain you suffered without letting that pain define you, enabling you to heal and move on with your life.