The purpose of absurdity[ref]Hattip: Junior Ganymede. EDITED ON 2017-Jun-06: I started this post with a link, but I have removed it because the site been flagged as a site holding malware, and so I’ve removed it. If you’re feeling brave, you can reconstruct from history|cultural-china|com/en/38History5846.html[/ref] is a blog post that goes a little deeper into conspiratorial waters than I’m willing to go, but still raises an issue that I believe is worth considering.

Many folks have observed that, especially as you move out towards the fringes of socially liberal dogma, the ideology becomes increasingly self-defeating and self-contradictory. For some humorous examples, consider the College Humor sketches This Video Will Offend You and if it Doesn’t I’ll be Offended and The Social Consequences of Everything. For a more serious treatment of the absurdity, consider John McWhorters article for The Daily Beast: The Privilege of Checking White Privilege:

I firmly believe that improving the black condition does not require changing human nature, which may always contain some tribalist taints of racism. We exhibit no strength—Black Power—in pretending otherwise. I’m trying to take a page from Civil Rights heroes of the past, who would never have imagined that we would be shunting energy into trying to micromanage white psychology out of a sense that this was a continuation of the work of our elders.

Or, you know, pick any of the numerous recent articles like this one: Classical Mythology Too Triggering for Columbia Students. If you’re still not convinced, just go with it for the sake of argument: elements of socially liberal politics are absurd.[ref]Conservatives believe silly things too, but that’s not what this post is about.[/ref]

So the question then becomes, not to put too fine a point on it: so what? Say that the philosophical premises of transgenderism (e.g. gender essentialism) conflict with the philosophical premises of feminism (gender is a social construct), so what? Why don’t we just go ahead and accept philosophically contradictory premises if it’s what makes people feel better. Are we really such sticklers for logical precision that we put cold rationality ahead of people’s lived experiences? What harm could it do?

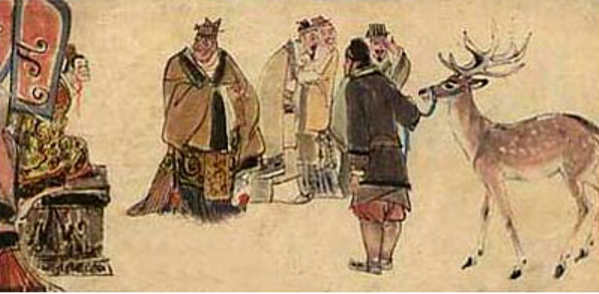

Believe it or not, I think that’s a serious question. And it deserves a serious answer. Which takes me back to that initial link on the purpose of absurdity. Here’s the basic story. A Chinese minister named Zhao Gao helps Huhai usurp the throne and then assassinates a whole bunch of potential rivals to secure Huhai’s claim as emperor. But then Huhai starts to be difficult to manage. And so:

Zhao Gao didn’t like that. He started to think that maybe they should have a change of emperor, but he couldn’t be sure he could pull it off.

So Zhao Gao brings a deer into the palace. Grabs it from the horns, calls the emperor to come out, and says “look your majesty, a brought you a fine horse”. The Emperor, not amused, says “Surely you are mistaken, calling a deer a horse. Right?”. Then the emperor looks around at all the ministers. Some didn’t say a word, just sweating nervously. Some others loudly proclaimed what a fine horse this was. Great horse. Look at this tail! These fine legs. Great horse, naturally prime minister Zhao Gao has the best of tastes.

A small bunch did protest that this was a deer, not a horse. Those were soon after summarily executed. And the Second Emperor himself was murdered some time later.

The point of the story, of course, is that it doesn’t really matter at all if you call a deer a horse. But asking people to go along with something that is simply not true is a really good way of identifying the troublesome folks and removing them. And then I think of the way Ryan T. Anderson has been ostracised or Brandon Eich got hounded out of his job. Set aside, just for the moment, the substantial issue of whether or gay marriage is right or wrong and just ask the more general question: how does society treat our dissidents? How do we treat the people who sincerely believe that they are being asked to go along with something that is simply not true?

The costs of speaking your mind on these issues is becoming very, very high. Perhaps to the point where–even if you agree with gay marriage (as Damon Linker and Andrew Sullivan)–the social cowing of dissidents and iconoclasts has gone too far.

This sentence struck me: “How do we treat the people who sincerely believe that they are being asked to go along with something that is simply not true?” I’ve heard the phrase “sincerely believe” from conservatives a lot recently, and what strikes me about it is how relativist it is. What should the cost of speaking your mind about something important and being wrong in a way which does harm be? If a legislator backs a bill which has the opposite of its intended effect, shouldn’t we trust her judgment less thereafter and be more likely to vote her out of office, regardless of whether she sincerely believed her claims? If a writer writes something which is not only false but harmful, are we obliged to continue reading his writing simply because to do otherwise would be to punish him for his deviation from orthodoxy?

Because I think that’s what’s at the root of the problem–the liberals you’re concerned about sincerely believe that voicing opposition to gay marriage not only rests on false premises, but does harm to our society. It’s exactly the deference for sincere belief which seems to me to cause the desire to remove one’s association with those who leave the liberal script. My own preference would be to step back from what you sincerely believe, and restore the primacy of what you can demonstrate with evidence. That which you sincerely believe but cannot demonstrate with evidence you ought not punish others for disagreeing with.

Kelsey-

The setup of your question is interesting, because it implies we live in a world where it’s relatively easy and unambiguous to assess the consequences of policy decisions. In such a universe, your contention would be very pressing.

But the universe we live in is pretty much diametrically opposed to that one. We rarely know with any degree of confidence what the causal results of any policy are, and even if we do: we don’t actually know what the casual results of alternative policies (including inaction) would have been.

See, to my mind the problem is not so much that conservatives harm society. Far from it, I think that in general social conservatism is much, much healthier from society. But the deeper and more truly “liberal” (in the modern sense of centralized planning and collectivism) assumption that underlies your critique is precisely that we have available the answer to the question of what harms society.

We don’t.

And, what’s more, the erroneous belief that we do seems in my mind to tend towards policies that–while we can’t be certain–are probably linked to social dysfunction in no small part because they (the policies and the assumption of easily available knowledge that go with them) both come stem from a common failure. That failure being the dramatic oversimplification of social models that tempts towards social engineering and, while we’re at it, skews the social engineering in harmful directions.

This is nihilistic in a benign sort of way in theory since–if you’re going to take it seriously–you will quickly find that there’s virtually nothing that “you can demonstrate with evidence.” Especially if, like me, you think Hume was largely right. (In which case, you can demonstrate literally nothing with evidence.)

But in practice it’s much worse than benignly nihilistic (e.g. self-defeating.) Because in practice it always ends up provoking an arms race to build up authority to dictate what is or is not acceptable as evidence.