The WaPo has an article claiming that there is no free-speech crisis, and providing stats to back up the claim. The article did not convince me. Here’s why.

It’s Not Just About Free Speech

The decline of free speech on college campuses is not the root problem; it’s a concerning symptom of a broader malady. In particular, the folks who are concerned about this issue[ref]And it’s a long list, including folks from left, right and center, which I’ve researched in pieces like this one.[/ref] posit that there’s a tendency of a radical minority to shut down political discourse as a political tactic. Although a lot of problems in the country are bipartisan, this one isn’t. It’s a peculiarly left-wing malady that reflects a growing contempt by many on the modern left for the values of liberalism that once defined it. I mean liberal in the old sense of the word, as in emphasizing individualism.

This isn’t an accusation from the outside, by the way, it’s an avowed element of one of the core intellectual components of Critical Race Theory. One definition states flatly that “CRT also rejects the traditions of liberalism and meritocracy.”[ref]This isn’t some random, convenient definition I found. It’s the #2 search result for “critical race theory” and comes from the UCLA School of Public Affairs. Not sure Kimberlé Crenshaw, the founder of Critical Race Theory itself, had anything to do with it, but she is a professor at the UCLA law school.[/ref]

So it’s not that there’s this explicitly anti-free speech trend in college campuses. It’s that there’s a virulent new ideology that uses attacks on free speech as a first resort.

Not All Speech is Equal

This being the case, looking for general survey results that attack free speech is misguided on multiple levels. First, it’s possible that the anti-free speech crowd are too small to register much in surveys but still powerful enough to create a climate of fear. In fact, that’s basically exactly what people concerned about this issue are saying. Second, even if you can get a survey with enough granularity to pick up on this minority, they aren’t opposed to free speech in all cases, but only in some cases. If you ask them about the wrong cases, you won’t measure anything at all.

Bearing that in mind, what kind of survey does the WaPo piece rely on? One that asks whether or not gay people should be allowed to give a speech. I kid you not. That, and an example about an anti-American Muslim cleric, are the leading examples. If you wanted to design survey results to be willfully blind to the actual concern, you couldn’t do better than this.

What are We Trying to Measure?

Speaking of willfully blind, the last section[ref]I’m skipping the second section because my problems with it are minor in comparison[/ref] cites research by the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education that there were only 35 no-platforming attempts in 2017 with only 19 being successful. So, “In a country with over 4,700 schools, that hardly constitutes a crisis.”

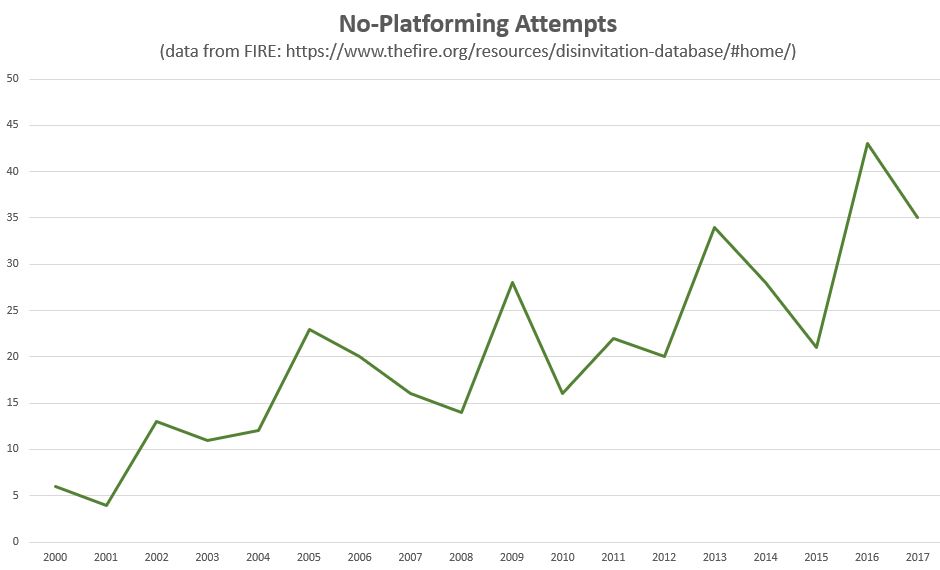

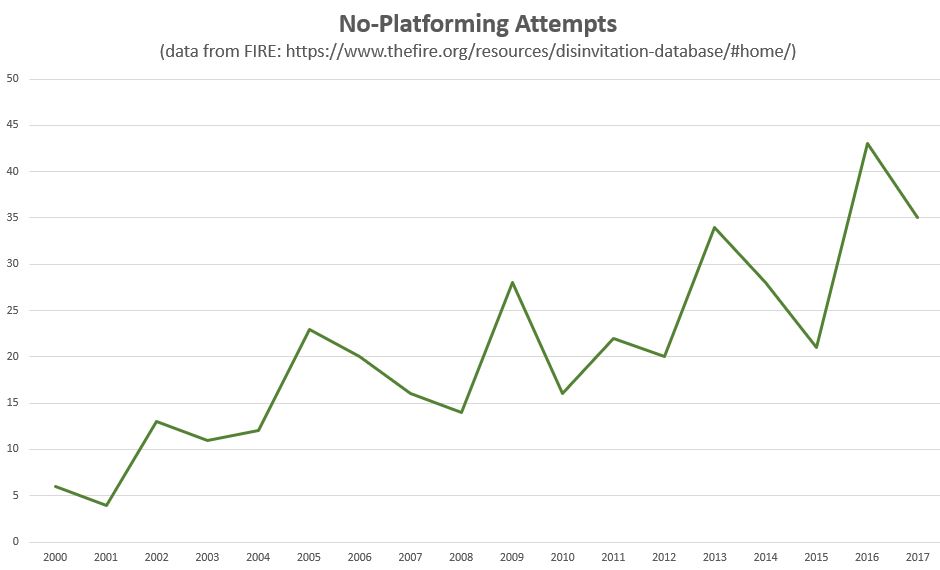

The meaningless of this statistic is impressive, given that Jeffrey Adam Sachs went to the trouble of finding and citing a dataset, but apparently not copy-pasting it into Excel to do some super-basic charting. Your first question might be, “Well, 35 attempts in 2017 doesn’t sound too bad, but is there a trend?” That would be anybody’s first question, I’d think, and here’s what that chart looks like:

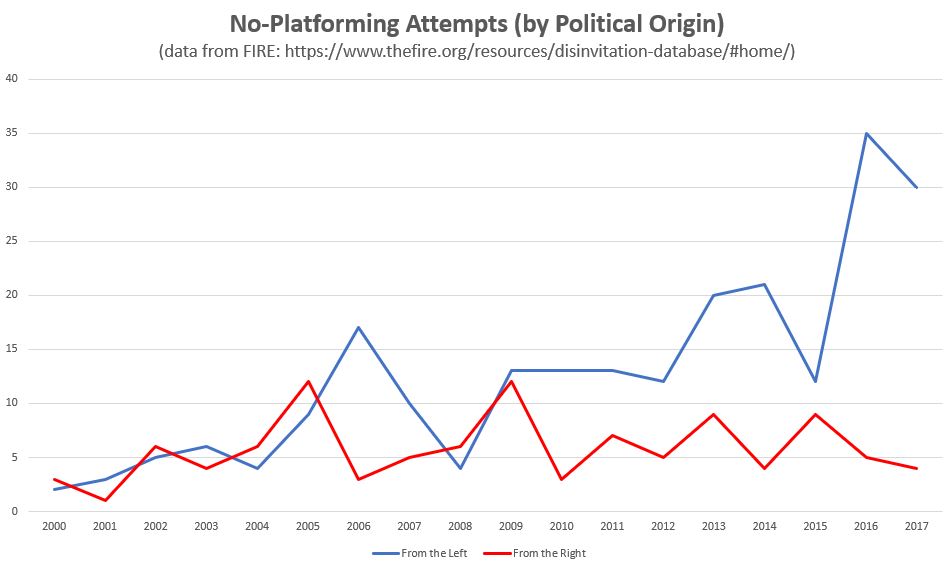

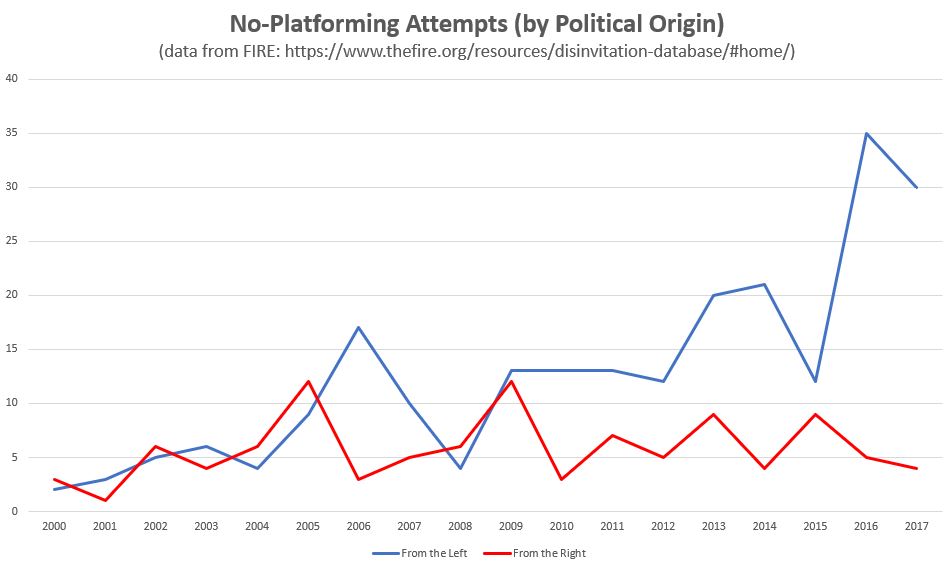

Well, gee. There’s an upward trend if ever I saw one. And remember, we said that this was an ideologically-biased trend. FIRE helpfully sorts the no-platforming attempts into left and right, so what does that breakdown look like?

We’ve got a more or less flat line from the right, and a pronounced, multi-year upward trend for the left starting a little less than 10 years ago. It’s almost as though all those people who are worried about a disturbing new anti-free speech trend coming from the political left might have something in the data to substantiate their concerns! Again: the same dataset that Sachs cited (but apparently didn’t really look at).

This doesn’t go directly to Sachs’ claim that 35 incidents out of 4,900 universities isn’t enough to care about, but that’s a questionable assumption if ever there was one. First of all, I’m curious as to what Sachs’ threshold is. How many times do left-wing radical have to shut-up speakers they don’t like in specifically the places ostensibly designated for discussing controversial, diverse ideas before it becomes a problem?

And then there’s the fact that this doesn’t reveal anything about how many controversial speakers never get invited at all because administrators don’t want to deal with protests? Counting free speech in terms of protests is fundamentally a strange concept. I would expect both a libertarian utopia and an Orwellian dystopia to have essentially zero protests, so what does the absence of protests say about free speech? Only that it’s not an issue. When it’s as prevalent as the air we breath, no one protests. And when it’s completely repressed, no one protests.

But when free speech is in a transitional period–away from or towards repression–well that’s when I’d expect to see a spike.

And keep in mind: there’s a lot more going on than just no-platforming. One of the most important functions of no-platforming is not only to dissuade controversial speakers from visiting the campus, but to create a climate of ideological intolerance and intimidation that keeps ordinary students from speaking their minds, something that is going on, as Sachs concedes: “Very conservative students also tend to report that they are less comfortable expressing themselves in the classroom than very liberal students.”

Final Thoughts

Some folks might not like that I’ve singled out the left in this piece, especially when I try to be even-handed. I get that. I do try to be even-handed. That’s not going to change. This post doesn’t represent a new, angrier, more partisan turn for me. This just happens to be one, specific, exceptional case where the cards don’t break evenly. The left has a bigger problem here.

But that doesn’t mean the right doesn’t have one! You could easily say that Trump’s populism and the entire Alt-Right is nothing but the right’s attempt to catch up with the left’s new-found identical politics. And you’d be right. And, lamentably, the right is a fast learner in this regard. It could very well be that–shortly–the right will have caught up with its own radical fringe of anti-free speech zealots.

Whether or not you call this a “crisis” is just semantics. What does seem evident is that there is a rise in no-platforming protests, that it is stemming primarily from the left, and that it is happening at the same time as a tide of research indicates ideological discrimination on campuses is widespread and pernicious for both students, professors, and research. For more on that, just check up on the Heterodox Academy’s problem statement.

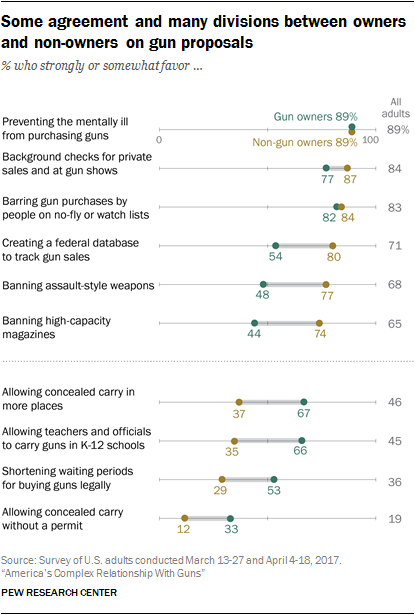

CNN ran an article detailing how student activists “led” the Washington, D.C., March for Our Lives rally on Saturday, downplaying the heavy organizational support they received from adult gun control advocates. Recent survey data show that only 10 percent of rally attendees were under 18 and the average age of the adults present was 49. And while most of the press coverage has implied that young people are overwhelmingly in favor of more gun control, comments from actual young people suggest their views are not quite so monolithic.

Putnam isn’t alone in his finding — studies in

Putnam isn’t alone in his finding — studies in

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/10328631/POLICIES_AND_OUTCOMES_CHART.png)

In an

In an