Earlier this morning I read an article in The Verge about the resurgence of rogue-like games, which the author characterized with three core traits: “turn-based movement, procedurally generated worlds, and permanent death that forces you to start over from the beginning.” So far so good, but the author then added one additional, non-essential characteristic:

They also often have steep learning curves that force you to spend a lot of time getting killed before you understand how things actually work.

And that’s when I lost my mind.

“Steep learning curve” does not mean what Andrew Webster thinks it does. Yes, yes, I know: someone is wrong on the Internet. Egads! We can also bring up the usual academic description: should linguistics be descriptive (merely documenting how people talk) or should it be prescriptive (laying down grammatical rules and standardized definitions). In the long run, words mean whatever people think they mean. Nothing more and nothing less. So I might be appalled by the fact that everyone uses “enormity” as though it meant “enormousness” these days[ref]It actually means “great evil,” or at least is used to.[/ref], but as a general rule I sigh, shake my head, and get on with my life.

The reality, of course, is that most of us understand grammar as a mixture of following the rules and knowing when to ignore or break them. The Week published a list of 7 bogus grammar ‘errors’ you don’t need to worry about, and their last category was “7. Don’t use words to mean what they’ve been widely used to mean for 50 years or more.” For example, the word “decimate” originally meant to kill 1/10th. It derives from a particularly brutal form of Roman military discipline[ref]”A cohort (roughly 480 soldiers) selected for punishment by decimation was divided into groups of ten; each group drew lots…, and the soldier on whom the lot fell was executed by his nine comrades, often by stoning or clubbing.” – Wikipedia[/ref] so it’s not a happy word, but it certainly doesn’t mean “to kill just about everyone.” Except that these days, it pretty much does, and you’ll get strange looks if you used it in any other way. How long before “enormity” goes on a similar list, and only out-of-touch cranks cling to its older definition and go on rants about ancient military laws?

It’s also worth pointing out that a lot of linguistic innovation is pretty fun and cool. For example: English Has a New Preposition, Because Internet.

But I draw the line at “steep learning curve” because we’re not just talking about illiteracy. We’re talking about innumeracy[ref]See? I’m down with neologisms[/ref].

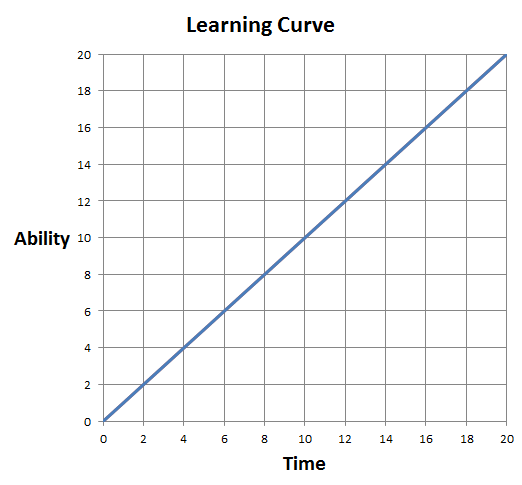

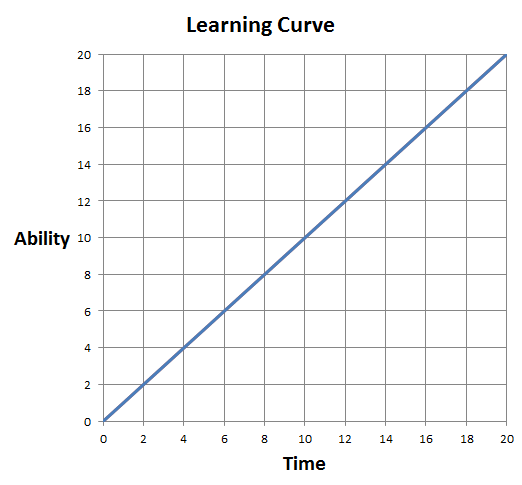

A learning curve is a graph depicting the relationship between time (or effort) and ability. Time is the input: we put time into studying, practicing, and learning. And ability is the output: it’s what we get in return for our efforts. Generally we assume that there will be a positive relation between the two: the more you practice piano the better you’ll be able to play. The more you study your German vocabulary, the more words you will learn.

The graph right above this paragraph shows a completely ordinary, run-of-the-mill learning curve.[ref]Don’t worry that it’s actually a straight line. That’s just faster to make in Excel.[/ref] What units are we measuring ability and time in? Doesn’t matter. It would depend on the situation. Time would usually be measured in seconds or minutes or whatever, but in physical practice maybe you’d want to measure it in calories burned or some other metric. And ability would vary to: number of vocab words learned, percent of a song played without errors, etc. Now let’s take a look at two more learning curves:

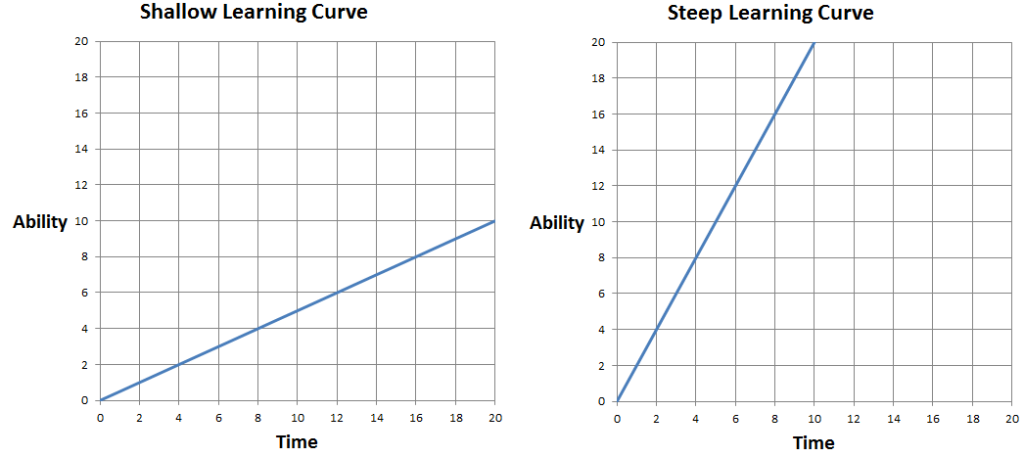

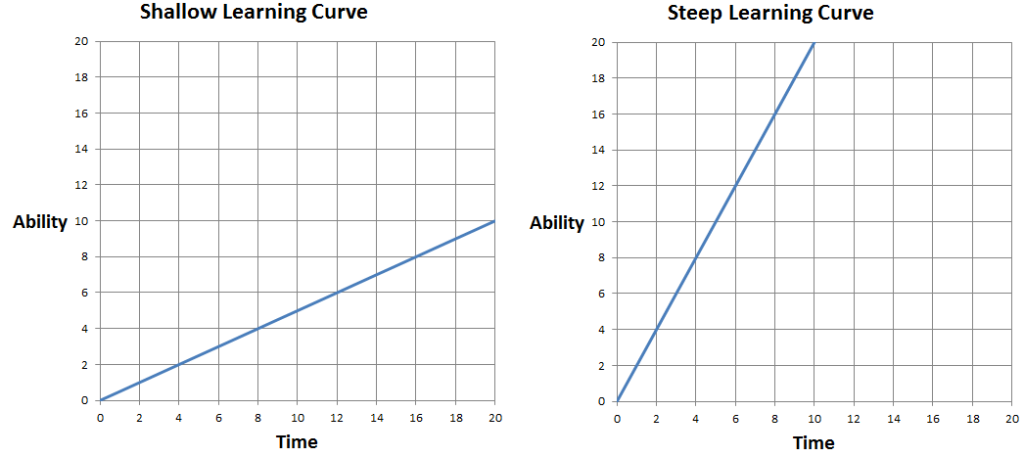

The learning curve on the left is shallow. That means that for every unit of time you put into it, you get less back in terms of ability. The learning curve on the right is steep. That means that for every unit of time you put into it, you get more back in terms of ability. So here’s the simple question: if you wanted to learn something, would you prefer to have a shallow learning curve or a steep learning curve? Obviously, if you want more bang-for-the-buck, you want a steep learning curve. In this example, the steep learning curve gets you double the ability for half the time!

You might note, of course, that this is exactly the opposite of what Andrew Webster was trying to convey. He said that these kinds of games require “you to spend a lot of time getting killed before you understand how things actually work.” In other words: lots of time for little learning. In other words, he literally described a shallow learning curve and then called it steep. Earlier this morning my son tried to tell me that water is colder than ice, and that we make ice by cooking water. That’s about the level of wrongness in how most people use the term “steep learning curve.”

It’s not hard to see why people get confused on this one. We associate steepness with difficulty because it’s harder to walk up a steep incline than a shallow one. Say “steep” and people think you mean “difficult.” But visualizing a tiny person on a bicycle furiously peddling to get up the steep line on that graph is a fundamental misapprehension of what graphs represent and how they work. By convention, we put independent variables (that’s the stuff we can control, where such a category exists) on the x-axis and dependent variables on the y-axis (that’s the response variable). Intuitions about working harder to climb graphs don’t make any sense.

Now, yes: it’s by convention that we organize the x- and y-axis that way. And conventions change, just like definitions of words change. And the convention isn’t always useful or applicable. So you could argue that folks who use the term “steep learning curve” are just flipping the axes. Right?

Wrong. First, I just don’t buy that folks who use the term have any such notion of what goes on which axis. They are relying on gut intuition, not graph transformations. Second, although the placement of data on charts is a convention, it’s not a convention that is changing. When people get steep learning curve wrong, they are usually not actually talking about charts or data at all, so they are just borrowing a technical term and getting it backwards. It’s not plausible to me that this single instance of getting the term backwards is actually going to cause scientists and analysts around the world to suddenly reverse their convention of which data goes where.

People getting technical concepts wrong is a special case of language where it does make sense to say that the usage is not just new or different, but is actually wrong. It is wrong in the sense that there’s a subpopulation of experts who are going to preserve the original meaning even if conventional speakers get it wrong and it’s wrong in the sense of being ignorant of the underlying rationale behind the term. Consider the idea of a quantum leap. This concept derives from quantum mechanics, and it refers to the fact that electrons inhabit discrete energy levels within atoms‘. This is–if you understand the physics at all–really very surprising. It means that when an electron changes its energy level it doesn’t move continuously along a gradient. It jumps pretty much directly from one state to the new state. This idea of “quanta“–of discrete quantities of time, distance, and energy–is actually at the heart of the term “quantum mechanics” and it’s revolutionary because, until then, physics was all about continuity, which is why it relied so heavily on calculus. If you use “quantum leap” to mean “a big change” you aren’t ushering in a new definition of a word the way that you are if you use “enormity” to mean “bigness”. In that case, once enough people get it wrong they start to be right. But in the case of quantum mechanics, you’re unlikely to reach that threshold (because the experts probably aren’t changing their usage) and in the meantime you’re busy sounding like a clueless nincompoop to anyone who is even passingly familiar with quantum mechanics. Similarly, if you say “steep learning curve” when you mean “shallow learning curve” then you aren’t innovating some new terminology, you’re just being a dope.

Maybe it doesn’t matter, and maybe it’s even mean to get so worked up about technicalities. Then again, lots of people think the world would be a better place if people were more numerate, and I think there’s some truth to that. In any case, I’m a nerd and the definition of a nerd is a person who cares more about a subject than society thinks is reasonable.[ref]There’s a reason Cyrano de Begerac is my hero: “What? It’s useless? I know. A man doesn’t fight to win./It’s better when the fight is in vain.”[/ref]

Most importantly, however, if you get technical terms wrong you’re missing out. Because the term were chosen for a reason, and taking the time to learn that reason will always broaden your mind. One example, which I’ll probably write about soon, is the idea of a technological singularity. It’s a trendy buzzword you probably here futurists and sci-fi aficionados talking about all the time, but if you don’t know where the term originates (i.e. from black holes) then you won’t really understand the ideas that led to the creation of the term in the first place. And they are some pretty cool ideas.

So yeah: on the one hand this is just a rant from a crotchety old man telling the kids to get off his lawn.[ref]And turn down their music.[/ref] But my fundamental motivation is that I care about ideas and about sharing them with people. I rant with care. It’s a love-rant.