Modern journalism often makes me want to go lay down in the middle of I-35 during rush hour traffic. I’ve complained about economic illiteracy before, but I think this one from Pacific Standard takes the cake. It begins,

These days it seems you can’t talk about socialism without being required to talk also about Venezuela—largely because certain people on the right bring up the failures of Venezuela every time the word “socialism” appears. Right-wing pundits claim incessantly that socialist policies are to blame for the terrible conditions that Venezuelans are now living through.

But this story is fundamentally false.

And who does the author consult to establish the falsity of this story?

- A Marxist (Wolff), which is about as fringe as fringe can get in economics. Marxists are the anti-vaxxers of mainstream economics.

- A supporter of Modern Monetary Theory (Galbraith), which has virtually no support among mainstream economists.

- Noam Chomsky.

The author declares,

Most crucially, it was a government rife with corruption that shattered Venezuela…Anat Admati, a professor of economics and finance at Stanford University, tells me that corruption can devastate any country. Regardless of the ideology that inspires your economic policies, Admati says, if there’s too much corruption, the country will fail…Corruption, not socialism, is the malignant tumor on democracy worldwide—in Venezuela, yes, but also here at home.

First off, to say socialism has nothing to do with Venezuela’s collapse is absurd. A 2018 report from the Council of Economic Advisers provides a rundown of some of Venezuela’s socialist policies, from the nationalization of industries (such as oil) to heavy taxation on earning and spending to price controls. Using a synthetic control methodology, economists Kevin Grier and Norman Maynard compared Venezuela’s performance under Hugo Chavez to its expected performance based on similar oil-producing, non-socialist Latin American countries. They find that “after 1998 (the year of Chavez’s successful presidential campaign) synthetic and actual Venezuela sharply diverge. By 2003, Venezuelan per-capita income is more than $3500 below that of synthetic Venezuela, and the gap exceeds $2500 in all subsequent years. It appears that Chavez’s leadership and policies were quite bad for the overall level of wealth in Venezuela” (pg. 8). They conclude, “We find that although average incomes rose somewhat during his time as president, they lagged far behind where they might have been if Chavez had not taken office” (pg. 14). In short, the oil boom masked Venezuela’s socialist underbelly. When the oil prices collapsed, the rot was exposed.

Even still, to say that “corruption, not socialism” led to Venezuela’s downfall reminds me of a quip by the assassin Vincent (played by Tom Cruise) in the film Collateral. After a dead body falls on his cab and the realization sinks in that Vincent is responsible, a shocked Max (Jamie Foxx) says, “You killed him!” Vincent, unfazed, responds, “No, I shot him. The bullets and the fall killed him.” It’s a distinction without a difference.

In their book Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty, Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson distinguish between inclusive and extractive institutions, with the former creating the conditions for prosperity. “Inclusive economic institutions,” they write,

…are those that allow and encourage participants by the great mass of people in economic activities that make best use of their talents and skills and that enable individuals to make the choices they wish. To be inclusive, economic institutions must feature secure private property, an unbiased system of law, and a provision of public services that provides a level playing field in which people can exchange and contract; it also must permit the entry of new business and allow people to choose their careers…Inclusive economic institutions foster economic activity, productivity growth, and economic prosperity (pg. 74-75).

In other words, inclusive institutions are largely free-market economies. On the other hand, extractive economic institutions lack these properties and instead “extract incomes and wealth from one subset of society to benefit a different subset,” empowering the few at the expense of the many (pg. 76).

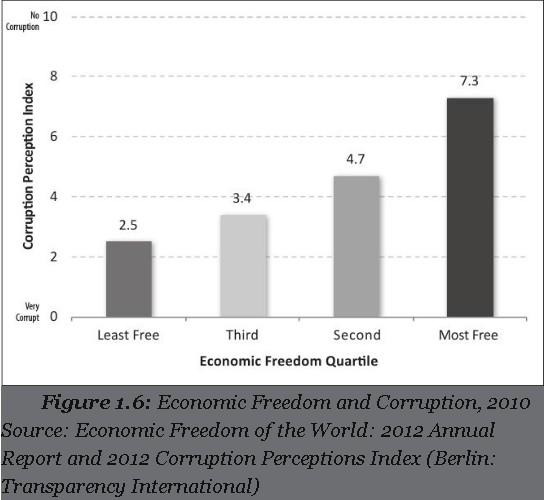

The Fraser Institute’s Economic Freedom of the World (EFW) Index, published in its annual Economic Freedom of the World reports, defines economic freedom based on five major areas: (1) size of the central government, (2) legal system and the security of property rights, (3) stability of the currency, (4) freedom to trade internationally, and (5) regulation of labour, credit, and business. According to its 2018 report (which looks at data from 2016), countries with more economic freedom have substantially higher per-capita incomes, greater economic growth, and lower rates of poverty. This makes economic freedom an excellent proxy for Acemoglu & Robinson’s “inclusive institution.” What’s more, Venezuela comes in dead last in the list of 162 countries.[ref]It’s also 188 of 190 in the World Bank’s latest Doing Business report.[/ref] Drawing on the EFW Index, Georgetown political philosophers Jason Brennan and Peter Jaworski point to a strong positive correlation between a country’s degree of economic freedom and its lack of public sector corruption.[ref]This could be in part due to economic growth undermining corruption and economic freedom promoting growth.[/ref]

“Corruption,” writes economist Joseph Connors, “is institutionalized exploitation and…it becomes institutionalized in the least capitalist countries. Transparency International, the creator of the Corruption Perception Index, is an organization dedicated to eradicating corruption. According to its metric of corruption, people who live in capitalist countries experience significantly less corruption than people in less capitalist countries. Market competition helps explain why this is true. Market competition diffuses power, and corruption thrives on centralized power. Thus, capitalism provides the environment that allows markets to keep corruption at bay.”[ref]Joseph Connors, “Is Capitalism Exploitative?” in Counting the Cost: Christian Perspectives on Capitalism, ed. Art Lindsley, Anne R. Bradley (Abilene, TX: Abilene Christian University Press, 2017), 130-131.[/ref]

Granted, a lack of corruption could very well give rise to market reforms and increased economic freedom instead of the other way around. However, recent research on China’s anti-corruption reforms suggests that markets may actually pave the way for anti-corruption reforms. Summarizing the implications of this research, Lin et al. explain,

Reducing corruption creates more value where market reforms are already more fully implemented. If officials, rather than markets, allocate resources, bribes can be essential to grease bureaucratic gears to get anything done. Thus, non-[state owned enterprises’] stocks actually decline in China’s least liberalised provinces – e.g. Tibet and Tsinghai – on news of reduced expected corruption. These very real costs of reducing corruption can stymie reforms, and may explain why anticorruption reforms often have little traction in low-income countries where markets also work poorly. China has shown the world something interesting: prior market reforms clear away the defensible part of opposition to anticorruption reforms. Once market forces are functioning, bribe-soliciting officials become a nuisance rather than tools for getting things done. Eliminating pests is more popular than taking tools away … A virtuous cycle ensues – persistent anticorruption efforts encourage market-oriented behaviour, which makes anticorruption reforms more effective, which further encourages market oriented behaviour.

There is also evidence that suggests that more government fingers in the pies increases corruption. For example, a 2017 study finds that larger municipality councils in Sweden result in more corruption problems. A 2009 study finds that more government tiers and more public employees lead to more bribery. Finally, a 2015 study shows that high levels of regulation are associated with higher levels of corruption (likely because of regulatory capture).

So while some may think socialism couldn’t have crippled Venezuela because Sweden, they’re wrong. And wrong in a big way.