Sociologist W. Bradford Wilcox testified before a committee put together by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine on child poverty in the United States. The following comes from his testimony:[ref]The sources for Wilcox’s claims can be found in the full link.[/ref]

Research by Robert Lerman of the Urban Institute and Isabel Sawhill of the Brookings Institution, among others, suggests the growth of child poverty from the 1970s to the 1990s was driven, in part, by the rise of single-parent families and family instability over this time period. For instance, in 1970, 12% of children lived with a single parent; by 1990, 25% of children lived with a single parent. Their work indicates that more than half of the increase in child poverty over this period can be attributed to the decline of stable marriage as an anchor to family life in America. Since then, the retreat from marriage has slowed, which means that family structure has been less salient in the ebb and flow of child poverty. Nevertheless, this research suggests that child poverty would be markedly lower in the United States if more American parents were stably married.

In fact, the continuing relevance of marriage to economic well-being can be seen in two recent studies, both of which suggest that marriage per se is strongly related to poverty. My own recent research with the Institute for Family Study’s Wendy Wang indicates that Millennials who have formed a family by marrying first are significantly less likely to be poor than Millennials who have formed a family by having a child before or outside of marriage. After controlling for education, race, ethnicity, family-of-origin income, and a measure of intelligence/knowledge (AFQT scores), we find that Millennials who married before having any children are about 60% less likely to be poor than their peers who had a child out of wedlock. In fact, as shown in the figure below, 95% of Millennials who married first are not poor by the time they are in their late twenties or early thirties. So, even for the latest generation of young adults, it looks like marriage continues to matter.

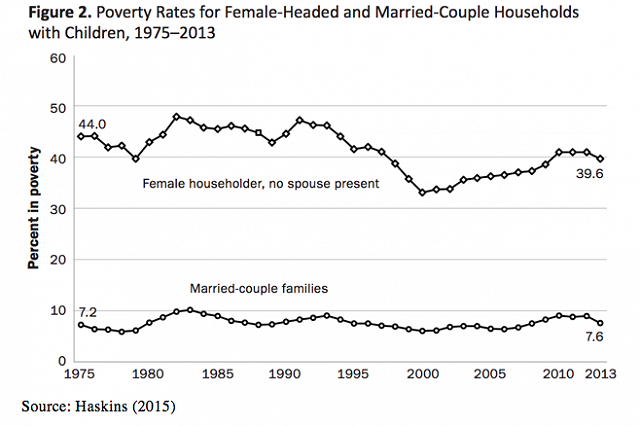

…[C]hildren in single-mother-headed families (who make up the clear majority of single-parent families) are over four times more likely to be poor, compared to children in married-parent families. And because more than one-quarter of American children are in single-parent families, this elevates the child poverty rate above what it would otherwise be if more children were living in married-parent families. Sawhill’s research suggests that if the share of children in female-headed families had remained steady at the 1970 level of 12.0%, then the 2013 child poverty rate would be at 16.4%, rather than a rate of 21.3%. In other words, the current child poverty rate would be cut by almost one-quarter if the nation enjoyed 1970-levels of married parenthood.

What about cohabiting parents?

One recent study finds, for instance, that children born to cohabiting parents are almost twice as likely to see their parents break up, compared to children born to married parents, even after controlling for a number of socioeconomic factors. This means that children in cohabiting families are more likely to end up in single-parent families or complex families without both their biological parents, which increases their risk of being in poverty. All this suggests that cohabitation does not protect children from poverty as much as marriage does.

What are the economic benefits of marriage for children?

- “children raised by their married parents are much more likely to enjoy access to the economic support of their father over the course of their childhood, compared to children raised by single or cohabiting parents.”

- “married parents are more likely to enjoy economies of scale, compared to single parents, and to pool their income, compared to other types of families.”

- “stably married parents who do not have children with other partners do not incur child support obligations or legal expenses related to family dissolution that reduce their household income.”

- “having stably married parents is worth about an extra $40,000 in annual family income to children while growing up, compared to children being raised by a single parent.”

What are his policy recommendations?

- “On the educational front, strengthen vocational education and apprenticeship programs, so as to increase the vocational opportunities of the majority of young adults who will not get a four-year college degree.“

- “On the policy front, work to minimize marriage penalties facing lower-income families, perhaps by offering newly married Americans a “honeymoon” period of three years where their eligibility for means-tested programs would not end if they marry—so long as their household income is below a threshold of $55,000.”

- “On the cultural front, launch local, state, and federal campaigns on behalf of what Haskins and Sawhill have called the “success sequence,” where young adults are encouraged to get at least a high school degree, work full-time, and marry before having any children—in that order.”

- “On the civic front, encourage secular and religious organizations to be more deliberate about targeting Americans without college degrees.”

This shouldn’t surprise anyone that has kept up with my posts. But it’s always nice to have some of the most updated research on the matter.

land use controls have a more widespread impact on the lives of ordinary Americans than any other regulation. These controls, typically imposed by localities, make housing more expensive and restrict the growth of America’s most successful metropolitan areas. These regulations have accreted over time with virtually no cost-benefit analysis. Restricting growth is often locally popular. Promoting affordability is hardly a financially attractive aim for someone who owns a home. Yet the maze of local land use controls imposes costs on outsiders, and on the American economy as a whole.

land use controls have a more widespread impact on the lives of ordinary Americans than any other regulation. These controls, typically imposed by localities, make housing more expensive and restrict the growth of America’s most successful metropolitan areas. These regulations have accreted over time with virtually no cost-benefit analysis. Restricting growth is often locally popular. Promoting affordability is hardly a financially attractive aim for someone who owns a home. Yet the maze of local land use controls imposes costs on outsiders, and on the American economy as a whole.

Well, this should be obvious, but it still stings. I’ve experienced an

Well, this should be obvious, but it still stings. I’ve experienced an