Today I’ve been thinking about a First Things piece by Orthodox philosopher David B. Hart written several years ago on the festivities of New Year’s. He notes

that my family never observed the day when I was growing up, and always made a point of going to bed well before midnight on New Year’s Eve.

In part, I think, this was simply because everyone in my family tends to be of a somewhat reclusive temperament, and so is generally averse to loud noises, close crowds, or forced jollity. In larger part, though, I think we always saw New Year’s Day—when treated as a kind of feast day of its own—as a profane intrusion on the twelve days of Christmas, which was by far our favorite time of year. From Christmas Eve to Twelfth Night, we were fairly good at keeping the festal flames alight and really had no need of any other excuse for our good spirits.

There is, of course, a feast of the Church traditionally celebrated on January 1st: to wit, the Feast of the Circumcision, considered important not merely as a commemoration of an episode from the biography of Christ, but as a remembrance of the first blood shed by Christ for the sake of the world’s redemption. But that obviously has nothing whatever to do with the arrival of the new year. In fact, throughout the Middle Ages, there was little firm agreement regarding what day really marked the inauguration of a new year, even though the Roman mensal calendar was in continual use.

The “real” 12 days of Christmas (not the song), according to Christianity Today, are as follows:

The traditional Christian celebration of Christmas is exactly the opposite [of the modern version]. The season of Advent begins on the fourth Sunday before Christmas, and for nearly a month Christians await the coming of Christ in a spirit of expectation, singing hymns of longing. Then, on December 25, Christmas Day itself ushers in 12 days of celebration, ending only on January 6 with the feast of the Epiphany.

Exhortations to follow this calendar rather than the secular one have become routine at this time of year. But often the focus falls on giving Advent its due, with the 12 days of Christmas relegated to the words of a cryptic traditional carol. Most people are simply too tired after Christmas Day to do much celebrating.

…The three traditional feasts (dating back to the late fifth century) that follow Christmas reflect different ways in which the mystery of the Incarnation works itself out in the body of Christ. December 26 is the feast of St. Stephen—a traditional day for giving leftovers to the poor (as described in the carol “Good King Wenceslas”). As one of the first deacons, Stephen was the forerunner of all those who show forth the love of Christ by their generosity to the needy. But more than this, he was the first martyr of the New Covenant, witnessing to Christ by the ultimate gift of his own life. St. John the Evangelist, commemorated on December 27, is traditionally the only one of the twelve disciples who did not die a martyr. Rather, John witnessed to the Incarnation through his words, turning Greek philosophy on its head with his affirmation, “The Word was made flesh, and dwelt among us” (John 1:14, KJV).

On December 28, we celebrate the feast of the Holy Innocents, the children murdered by Herod. These were not martyrs like Stephen, who died heroically in a vision of the glorified Christ. They were not inspired like John to speak the Word of life and understand the mysteries of God. They died unjustly before they had a chance to know or to will—but they died for Christ nonetheless. In them we see the long agony of those who suffer and die through human injustice, never knowing that they have been redeemed. If Christ did not come for them too, then surely Christ came in vain. In celebrating the Holy Innocents, we remember the victims of abortion, of war, of abuse.

…In the Middle Ages, these three feasts were each dedicated to a different part of the clergy. Stephen, fittingly, was the patron of deacons. The feast of John the Evangelist was dedicated to the priests, and the feast of the Holy Innocents was dedicated to young men training for the clergy and serving the altar. The subdeacons (one of the “minor orders” that developed in the early church) objected that they had no feast of their own. So it became their custom to celebrate the “Feast of Fools” around January 1, often in conjunction with the feast of Christ’s circumcision on that day (which was also one of the earliest feasts of the Virgin Mary, and is today celebrated as such by Roman Catholics).

Hart explains that as an adult his own family somewhat celebrates New Year’s Eve/Day. “But, on the whole,” he writes, “it is still a minor observance for us, and nothing to compare to the celebrations we like to hold on Twelfth Night, the eve of Epiphany, when the last of the Christmas presents are opened, games are played, and the decorations come down from the tree. (I know many Americans think of Christmas as a single day and like to clear away the trappings of the season well before the fifth of January, but that is sheer barbarism, if you ask me, morally only a few steps removed from human sacrifice, cannibalism, or golf.) The long and the short of it, then, is that I have really nothing much to say about New Year’s Day.” He concludes, “Whatever the case, I hope any of you who plan to spend [New Year’s Eve] chasing after strange gods will find something of interest in it. At my house, however, we will still be celebrating Christmas.”

All in all, I find this appealing. Mormonism doesn’t have much of a Christmas tradition outside the American version, but this doesn’t mean we can’t draw on the traditions of our Christian neighbors. Perhaps celebrating “the first blood shed by Christ for the sake of the world’s redemption” on January 1st isn’t such a bad idea.

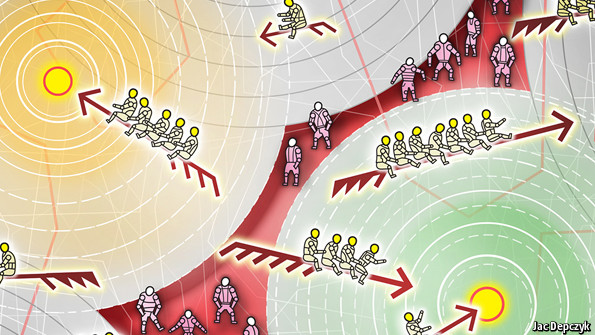

In a world with just two countries, one developed and the other poor, output is produced in each by a combination of skilled workers and unskilled workers. When they’re young, unskilled workers have the opportunity to become skilled by working with older, skilled workers.

In a world with just two countries, one developed and the other poor, output is produced in each by a combination of skilled workers and unskilled workers. When they’re young, unskilled workers have the opportunity to become skilled by working with older, skilled workers.

So write three scholars drawing on their

So write three scholars drawing on their