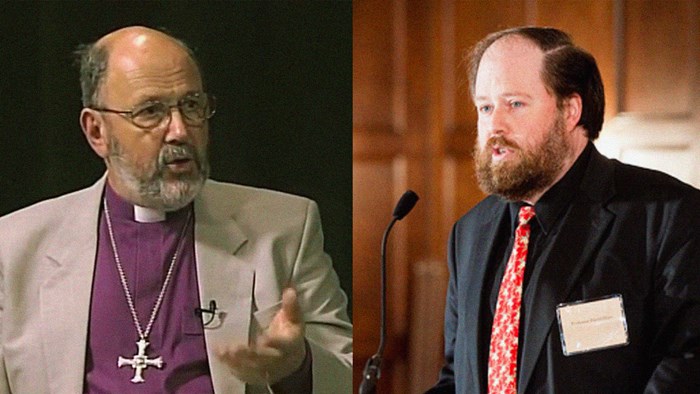

I’m a big fan of both Anglican New Testament scholar N.T. Wright and Eastern Orthodox theologian David B. Hart and have read a number of books by both. A few years ago, Wright published his translation of the New Testament. Hart recently published his own translation through Yale University. And apparently, the two have been sparring over Hart’s translation. According to Christianity Today,

One notable scholar who does not appear to be particularly impressed by Hart’s translation is Wright, who is probably the closest thing current New Testament scholarship comes to having a celebrity. His review of Hart’s New Testament, published January 15 in The Christian Century, details a lengthy list of disagreements with Hart’s translation choices, and ends with the backhanded compliment that Hart’s translation is “as idiosyncratic as it is bold.”

Wright’s primary concern seems to be Hart’s understanding and use of language—both Greek and English. Hart claims his translation will in many parts be “an almost pitilessly literal translation,” intending to “make the original text visible through as thin a layer of translation as I can contrive to superimpose upon it.”

While Wright seems to respect what Hart is trying to accomplish, he nevertheless argues that instead of making the original text visible, Hart may actually be obscuring it by trying to render Greek syntax and idioms in English. “Greek and English, as Hart knows well, do not work the same way,” Wright argues. “… The strange English here has nothing to do with a cultural clash between the first Christians and ourselves.”

Hart didn’t waste any time in his response:

Hart’s rejoinder is, like Wright’s initial review, full of zingers and jabs and worth a full read. Hart grants Wright a few basic premises, then wades right into the details of Wright’s critique—meeting him point for point, and then some. Hart notes in the comments on the blog post that he was “annoyed … that Wright wrote any review at all … because he has a competing version out there [published in 2011], and it’s an old rule that one doesn’t write reviews—especially caustic reviews—of competing books.”

Hart characterizes Wright’s review as a “catalogue of complaints,” and thinks that Wright’s own work “suffers from a dangerous combination of the conventional and the idiosyncratic, with a few significant historical misconceptions mixed in … imposing meanings on the text that best conform to his own convictions, plausible or not.” Hart concludes one particular point about how to translate a noun in Greek that lacks an article by saying, “Here I am right and Wright is wrong,” but it would not be a stretch to say that this statement characterizes much of Hart’s response.

So what’s the heart of the issue? The article concludes,

Where Wright is trying to translate the Greek of the New Testament (replete with its Greco-Roman and Second Temple Jewish valences) into modern English, Hart instead is attempting to translate the Greek of the New Testament (in all of its original “mysteries and uncertainties and surprises”) in modern English.

For Hart, the focus is communicating the “strangeness” of the Greek words and phrases themselves, which occasionally requires dips into esoteric vocabulary in order to find just the right word and a willingness to forgo normal syntax in order to allow the “Greekness” to come through. By contrast, for Wright the focus is communicating the strangeness of what those Greek words were conveying, meaning removing as many barriers to receiving and understanding the difference between a first-century viewpoint and our contemporary one.

They are both aiming at very similar goals, but their methods are starkly different. They both want the original to shine through as much as possible, to give, as Wright puts it, “a first-hand … understanding of what the New Testament said in its own world.” For Hart, this means making English say things as “Greekly” as he can manage; for Wright, it means making English mean Greek things as much as he can.

The translations of both of these scholars are impressive achievements, and both deserve praise and appreciation for their careful and dedicated work to produce them. Neither is necessarily “better” or “more faithful” than the other; they are simply aimed at different things (as their acrimonious repartee displays). Likewise, as both scholars attest in their introductions, neither of these translations is intended nor fit for regular use in church or for devotion. Rather, they both serve as valuable and faithful opportunities to encounter the text of the Bible anew and afresh.[ref]Understanding these contrasting approaches may be useful to Mormons when it comes to Joseph Smith’s “translations” of the Book of Mormon, Book of Abraham, and the Bible.[/ref]

Read the whole thing.