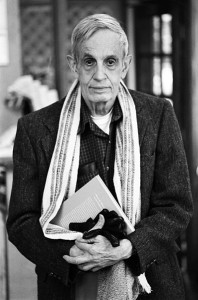

Nobel Prize-winning economist Ronald Coase died recently at the age of 102. Many fine tributes have been written over the past week, but a common theme in many of them is that Coase was an economist interested in what actually happens in the economy. Or, as he explains below, “the approach [to economics] should be empirical.”

Month: September 2013

Dog Saves Baby from Abusive Babysitter

From ABC News in Kentucky:

The parents of 7-month-old Finn Jordan suspected something was wrong last year when their dog began to growl and snarl at the babysitter, Alexis Khan, 22.

“We noticed the dog was getting very defensive when Alexis was around. He would growl and stand between her and our son. His hair would stand up on the back of his neck and we knew something was up,” Benjamin Jordan said.

The parents stashed an iPhone under a cushion to get a recording, expecting to hear the babysitter mistreating their dog. Instead they heard her swearing at the baby, along with the sounds of slapping and shaking. Police weren’t sure it would be enough for a conviction, but the babysitter confessed when interrogated and was sentenced to 3 years, the maximum, and had her name put on a list of child abusers to prevent her from ever working with children again.

Thankfully the little boy, who the parents rushed to a hospital right away, checked out just fine.

Good dog.

The Modesty Wars

I initially wrote this post as an irate response to this post from By Common Consent, but I decided to let it simmer for a few days. I knew that Angela C, who wrote that BCC post, didn’t really deserve to be singled out as the target for my ire when she was really just the straw that broke the camel’s back.

So, instead of tackling her post point-by-point, I want to get to what really fundamentally bothers me about the modesty wars. I guess I should start by defining the modest wars.

If you’ve never heard of the phrase that’s OK because, as far as I know, I just made it up. It refers to the odd feminist-vs-feminist battle between social conservatives and social liberals that centers primarily on modest dress. The conservative view is that immodest clothing is intrinsically sexually objectifying and therefore disempowers women. Probably the best proponent of this view comes from Caroline Heldman’s TEDxYouth talk.

The liberal response is basically that an emphasis on modest dress is the problem, not the solution, because it teaches both boys and girls to objectify their female bodies in the first place. Apparently liberals believe that, without specific training, no man would ever objectify women by ogling their bodies and that no woman would ever notice this and respond to it by intentionally inviting such objectification in exchange for leverage. Nope: that dysfunctional co-dependency is all thanks to capped-sleeves.

Love, Marriage, and the Mundane

I’ve seen this post making the rounds, and I like it quite a lot so I’m sharing it. The general message is that love isn’t an emotion (e.g. Disney, every rom-com ever) but rather it’s about choices we make. And that’s a good message.

But there’s one line in the post that really stuck out to me in particular, which is this:

Through giving, through doing things for my wife, the emotion that I had been so desperately seeking naturally came about. It wasn’t something I could force, just something that would come about as a result of my giving. In other words, it was in the practicality that I found the love I was looking for. (emphasis original)

This resonates with what I’ve written in the past about the relationship between the sacred and the mundane, and also with what Walker has written with his co-author (and DR commenter) Allen. It’s a beautiful message that’s easy to understand but hard to live by. Beauty, love, and all the ideals that we care about are there around us in the world, but we have to reach out and seize them through mundane actions rather than wait around for a non-existent life soundtrack to inform us that meaning is being rained down upon us by some cosmic director of our lives.

Phonebloks

I’m not sure how feasible this idea really is, but it feels like sci-fi, so I’m in.

If you can’t watch the video (or want the Cliff Notes version), Phonebloks is the idea of making cell phones fully modular by turning the individual components (battery, camera, CPU, storage, etc.) into little blocks that you can easily swap out and rearrange on your phone. The primary purpose is to make phones upgradeable to cut down on ewaste, but it has the added benefit of making phones highly customizable.

The campaign behind the idea–and at this stage it’s just an idea–is almost as interesting as the idea itself. They’re using a platform called Thunderclap to try and attract attention to the idea. Thunderclap is basically like Kickstarter except that instead of contributing cash you commit to automatically update your FB status, sent out a Tweet, whatever to support an idea. So if you like the Phonebloks idea you can visit the website and join the supporters. Then, on October 29, you and everyone else who has signed up will automatically post an FB status (Tweet, whatever you sign up for) and it will hopefully signal that this is an idea people care about.

The Slow Hunch: The Secular and the Sacred

Today’s post from The Slow Hunch was written on the 10th anniversary of 9/11. I’m a little late (it is after 11pm in Texas), but I still technically made it. Just a few thoughts on hope and redemption on a day that can sometimes convince us there is none.

A Game Theoretic View of the Atonement

Want to know one way to guarantee no comments on Times And Seasons? I decided to try “use lots of game theory” and see how that works. So far? Success. But if you think seeing the world as one giant, iterated Prisoner’s Dilemma sounds interesting, then maybe you should give it a read anyway.

Want to know one way to guarantee no comments on Times And Seasons? I decided to try “use lots of game theory” and see how that works. So far? Success. But if you think seeing the world as one giant, iterated Prisoner’s Dilemma sounds interesting, then maybe you should give it a read anyway.

I know I had fun writing it, and if I ever had the time, I’d love to actually formalize the model and try it out. Shifting from traditional economic models to complex systems was a major interest for me when I was studying at Michigan, and it would be great to scratch that itch again.

Reconciling Murray

GMU’s Bryan Caplan has an interesting 2012 post on reconciling the work of controversial political scientist Charles Murray. Caplan views Murray’s three main books on poverty–Losing Ground, The Bell Curve, Coming Apart–as complementary. To review:

– Losing Ground: American Social Policy, 1950-1980 criticizes the welfare state for giving the poor perverse incentives.

– The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life (written with the late psychologist Richard Herrnstein) argues that the poor tend to have lower IQs.

– Coming Apart: The State of White America, 1960-2010 claims that the poor are generally lacking in particular virtues and social norms, namely marriage, industriousness, religiosity, and honesty (in relation to rising crime rates).

Caplan sets it up as follows:

- “The Bell Curve emphasizes the most stable difference between the rich and the poor: The poor tend to be less intelligent. Cognitive ability is an important determinant of success in almost any society. Smarter workers are simply more productive, and competing employers reward them accordingly. In the long-run, therefore, people with low intelligence tend to have correspondingly low incomes.”

- “People with low IQs aren’t just less productive; they’re also more impulsive…Implicit: One of the best ways to help impulsive people reach decent long-run outcomes is to give them a lot of strong short-run feedback.”

- “In Losing Ground, Murray shows what happens when the welfare state shelters people from this short-run feedback.”

- “The impulsive are swayed more by guilt and shame than careful calculations about the distant future. In Coming Apart, Murray shows that over the last few decades, this tradition/social pressure mechanism has gradually broken down for the working class – and transformed the working class into a dysfunctional leisure class…Removing short-run feedback led to worse behavior, which undermined traditional norms about work and family, which reduced social pressure, which led to worse behavior.”

- “Elites live in a high-IQ, low-impulsiveness Bubble. When they introspect, they correctly conclude that the welfare state has little effect on their behavior. They then incorrectly infer that the welfare state has little effect on anyone‘s behavior.”

Dog (and gun) help disabled Middletown woman fend off intruder

A 64-year-old woman in Cincinnati, Mabel Fletcher, fended off a home intruder by firing three shots from her 9mm Glock. Police believe the intruder got into the home through a broken guest bedroom window. Fletcher’s dog, Benji, woke Fletcher shortly before the intruder entered her bedroom and attacked her. As Fletcher explains,

“I have heard of so many break-ins and I am a widow and I am by myself and I thought somebody could come in,” she said. “My dog could let me know, but if they could probably shoot him and then I’d have no protection and they could kill me. So I had to get me a weapon to protect myself.”

The intruder, who was not hit by Fletcher but did flee, turned out to be 21-year-old Paige Stacey. The police later found her asleep in a car, in possession of Xanax, heroin, Hydromorphone, and a syringe.

What is “unscientific”?

I recently had a discussion with an individual about the supposed incompatibility of religion and science. This individual was convinced that most of the central claims of any religion can be labeled as unscientific. I disagreed, but not simply because of my own convictions about the nature of God, but also because of my intuition about the limitations of science and why any questions or claims that lay beyond those limitations are not automatically “unscientific.”

I’d like to start by making reference to a related argument. In the very public, recent intelligent design vs science court case Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District, celebrated intelligent design proponent Dr. Michael Behe was forced to admit that his argument–that can be effectively summarized as follows:

the input of an intelligent designer is the only currently-known method for producing the strong appearance of design (theoretical arguments of evolutionists notwithstanding) that we find in complex biological organisms, and therefore the inference of a designer is rationally justified

is an inductive argument that can never be ruled out (is unfalsifiable). This “marginalization by unfalsifiability” was how Behe’s arguments were painted as “unscientific” and therefore unworthy of serious consideration. Falsifiability is how Karl Popper famously gave science an escape from Hume’s problem of induction. Falsifiability allows us to say that since it’s so difficult, if not impossible, to prove a claim absolutely true, we instead seek to prove it false, which is a far easier task. If your predictions cannot be shown to be false, they are generally considered to be unscientific. This is, of course, a rough and somewhat naive explanation of how science is done as scientists are more concerned with supporting or contradicting evidence surrounding a claim, but falsifiability is nonetheless a fairly reliable gauge of whether or not a specific claim can ever be considered “scientific.”

If these are the grounds on which we may rule out certain inductive arguments in terms of their “scientificity,” then I would like to suggest that, from a philosophical standpoint, we can similarly dismiss many more supposedly scientific arguments. As an illustration, let’s consider the varying and even competing hypotheses of abiogenesis–the natural process by which life arises from simple organic compounds, implicitly without the need of any intelligent input. That this process occurred at some point in earth’s history is, of course, the default position of most scientists. Any claims to the contrary simply remove the origins of life elsewhere in the universe without actually answering the central question. Scientists believe that either life can create itself from naturally occurring materials, or we lose all explanatory power about the origins of life since the input of an intelligent creator would necessitate an explanation of how that creator itself came to be.

Let’s examine both possibilities a bit more closely. How could we test that life arises from naturally occurring, simple compounds? We could formulate an experiment or series of experiments in which we mix such compounds under simulated pre-life earth conditions and see if such a process can produce a self-replicating molecule. If our experiments produce such a molecule, we have indeed confirmed that life can arise spontaneously from naturally occurring, simple organic compounds. Does this prove that life arose on earth in a like manner?

Well, no. It can, at best, only strengthen the claim that life arose on its own on earth. And in fact, since we can’t know the exact conditions under which life arose on earth, our test itself required the input of an intelligence to both create the test and then fine-tune its parameters. This forces us to explain the success of our experiment, which strengthens the claim we’ve made about the natural origin of life on earth, in terms of the actions of that life. What then to make of the explanatory power of abiogenesis?

What about our other theory–that life arose on earth with help? Attributing the origin of life on earth to a creator intelligence could require the exact same test–and in fact the same experiment we used to verify our predictions about the capabilities of natural abiogenesis could be used equally well to strengthen the claim of intelligent biogenesis. Where does that leave us?

Are any of the specific claims that follow from or precede our experiments falsifiable? Probably not, at least not without a time machine. Are they then unscientific? No. One of the biggest problems I have with reductionism is the ironically religious-like a priori rejection of claims without considering their merit and without serious introspection and a healthy sense of skepticism toward one’s own convictions.

The universe is a strange place, and I believe we will find it to be far stranger the more we learn about it. If a claim must fit our personal worldview, let’s at least allow others, especially those with whom we disagree, the same consideration. We might learn something.