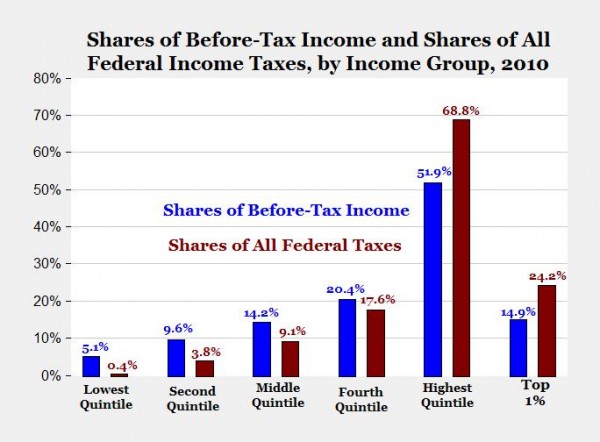

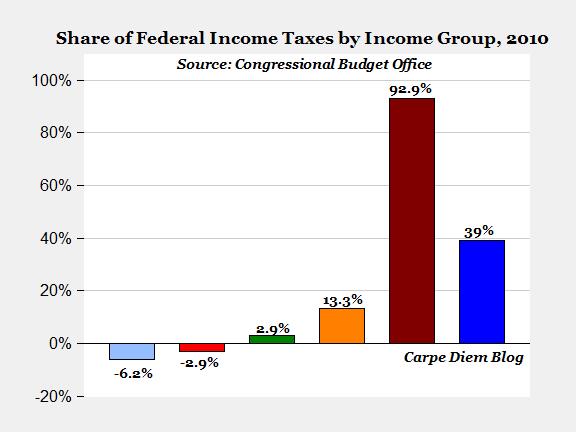

Drawing on data from the Congressional Budget Office, economist Mark Perry provides the following two charts:

“As the data show in the top chart,” writes Perry,

the shares of pre-tax income for the four lower income groups was greater than their shares of federal taxes paid in 2010. In contrast, the highest quintile earned about half (51.9%) of all income in 2010 but paid more than two-third (68.8%) of all federal taxes collected. The top 1% earned 14.9% of pre-tax income in 2010 but paid 24.2% of all federal taxes collected…The federal tax system is highly progressive (higher income households shoulder an increasingly greater tax burden), especially for federal income taxes, as the bottom chart shows. The top income quintile paid almost all federal income taxes in 2010 (94.1%), and the top 1% paid almost 39% of all income taxes. In contrast, the bottom two income quintiles actually had negative shares of income taxes in 2010 and were in fact “net tax receivers” because their refundable tax credits exceeded the income tax otherwise owed.

Not only do the top earners pay the highest amount of taxes, but it tends to be their innovations that benefit society as a whole. Yale economist William Nordhaus’ 2004 paper “Schumpeterian Profits in the American Economy: Theory and Measurement” found that innovators only capture 2.2% of the total present value of social returns. As GMU economist Don Boudreaux pointed out, “The smallness of this figure is astounding. If it is anywhere close to being an accurate estimate, the implication is that “society” pays a paltry $2.20 for every $100 worth of welfare it enjoys from innovating activities.”

The rich may be evil and all that, but they sure do pay for it.

Nice.

On a related note, you might be interested in this somewhat related article claiming that 60% of households receive more money from the Federal government than they pay.

Also, the frame of your post seems to give short shrift to the sense in which innovators stand on the shoulders of societal giants, as it were. That is, if you tried to properly account for the benefit innovators get from society, I suspect the “2.2% of the total present value of social returns” would look much smaller (though I haven’t looked at the paper carefully enough to make a more nuanced argument about how to parse contributions to innovation — I wonder, for example, how “consumption” of knowledge accounted for…).