In a 2011 post, historian John Fea acknowledged the idea that the United States is a “Christian nation” is typically associated with the Christian Right. People from Glenn Beck to Newt Gingrich have claimed America was founded and meant to be a Christian nation. “Rarely, if ever,” Fea writes, “do we hear the name Martin Luther King, Jr., included in this list of apologists for Christian America. Yet he was just as much of an advocate for a “Christian America” as any who affiliate with the Christian Right today”:

In a 2011 post, historian John Fea acknowledged the idea that the United States is a “Christian nation” is typically associated with the Christian Right. People from Glenn Beck to Newt Gingrich have claimed America was founded and meant to be a Christian nation. “Rarely, if ever,” Fea writes, “do we hear the name Martin Luther King, Jr., included in this list of apologists for Christian America. Yet he was just as much of an advocate for a “Christian America” as any who affiliate with the Christian Right today”:

King’s fight for a Christian America was not over amending the Constitution to make it more Christian or promoting crusades to insert “under God” in the Pledge of Allegiance (June 14, 1954). It was instead a battle against injustice and an attempt to forge a national community defined by Christian ideals of equality and respect for human dignity. Most historians now agree that the Civil Rights movement was driven by the Christian faith of its proponents. As David Chappell argued in his landmark book, Stone of Hope: Prophetic Religion and the Death of Jim Crow, the story of the Civil Rights movement is less about the triumph of progressive and liberal ideals and more about the revival of an Old Testament prophetic tradition that led African-Americans to hold their nation accountable for the decidedly unchristian behavior it showed many of its citizens.

King’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” “offered a vision of Christian nationalism that challenged the localism and parochialism of the Birmingham clergy and called into question their version of Christian America.” Furthermore,

King understood justice in Christian terms. The rights granted to all citizens of the United States were “God given.” Segregation laws, King believed, were unjust not only because they violated the principles of the Declaration of Independence (“all men are created equal”) but because they did not conform to the laws of God. King argued, using Augustine and Aquinas, that segregation was “morally wrong and sinful” because it “degraded “human personality.” Such a statement was grounded in the biblical idea that all human beings were created in the image of God and as a result possess inherent dignity and worth. He also used biblical examples of civil disobedience to make his point. Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego took a stand for God’s law over the law of King Nebuchadnezzar. Paul was willing to “bear in my body the marks of the Lord Jesus.” And, of course, Jesus Christ was an “extremist for love, truth, and goodness” who “rose above his environment.” …By fighting against segregation, King reminded the Birmingham clergy that he was standing up for “what is best in the American dream and for the most sacred values in our Judeo-Christian heritage, thereby bringing our nation back to those great wells of democracy which were dug deep by the founding fathers in their formulation of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence.”

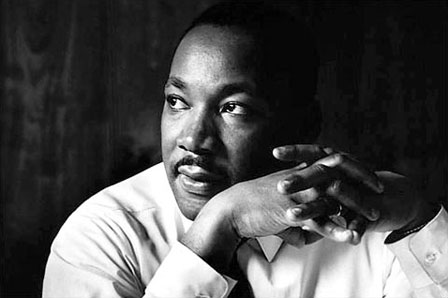

Every side of the political spectrum attempts to lay claim on the legacy of Martin Luther King, Jr.[ref]King’s policy suggestions were actually quite socialist in nature, especially later in life. See Thomas E. Woods, Jr., “Did Martin Luther King Jr. Oppose Affirmative Action?” in his 33 Questions About American History You’re Not Supposed to Ask (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2007).[/ref] But as one writer put it, “The texts we argue about most—the Bible, the Constitution, Orwell’s wartime essays, MLK’s civil rights sermons—are the ones whose force of enlightenment, poetry, passion, and morality have risen above the cacophany of human language to almost universally stir souls and inspire liberation. People don’t fight over words that only apply to one side of most arguments…Like the Declaration [of Independence] itself, MLK’s words were considered radical upon utterance, yet universal within a couple of generations.”

Jesus is often seen as a radical (even when he was at times more conservative in his interpretation of the Torah than his peers)[ref]For example, see his teaching on divorce (Matt. 19:3-9). The two rabbinic schools of Shammai and Hillel differed on the grounds for divorce. Shammai permitted divorce only in the case of adultery, while Hillel allowed divorce for almost any reason. Jesus sided with the former.[/ref] whose love was universal. In an effort to follow in his Master’s footsteps, King was also a radical advocating for the universal.

May we all be a bit more radical in pushing forward the universal.