In the past couple of months, Walker and I both read The New Jim Crow and found Michelle Alexander’s arguments that the War on Drugs and the American criminal justice system are racist serious and credible. Then, today, we read and talked about a Wall Street Journal opinion piece making the opposite case: The Myth of Mass Incarceration. I called dibs, so I get to blog about it.

In the past couple of months, Walker and I both read The New Jim Crow and found Michelle Alexander’s arguments that the War on Drugs and the American criminal justice system are racist serious and credible. Then, today, we read and talked about a Wall Street Journal opinion piece making the opposite case: The Myth of Mass Incarceration. I called dibs, so I get to blog about it.

The most striking thing about the WSJ piece (by Barry Latzer) is that although he seems to be alluding to Alexander’s work (and has cited her book in his own work), he ignores the fact that she has already anticipated and rebutted his central arguments. According to Latzer, violent crime is the main driver of mass incarceration, not drug convictions, and to back this up he cites some data. For example:

Relatively few prisoners today are locked up for drug offenses. At the end of 2013 the state prison population was about 1.3 million. Fifty-three percent were serving time for violent crimes such as murder, robbery, rape or aggravated assault, according to the BJS.

The numbers are not in dispute, but they don’t mean what Latzer thinks they mean. Let’s see how this works with a simple (but unrealistic) illustration.

Imagine that in a single year 12 people are given 1-month drug sentences. One serves in January, one serves in February, one serves in March, etc. In the same year, 1 person is given a 1-year sentence for murder. If you take Latzer’s approach and go count the number of inmates in jail and see what they’re in prison for than–no matter what month you pick–you’ll find 1 person in jail for drugs and 1 for murder. You would concludes that 50% of incarcerations are for drugs, and 50% are for violent crime.

But of course that’s not really true. There were twelve drug convictions in our example, not just one. So in reality the proportion of drug offense wasn’t 50%. It was more than 92%. The number is artificially lowered because the drug offenders served shorter sentences, and so taking a poll in the prison year is misleading.

The numbers are invented for this example, but the effect is not. Drug sentences are generally shorter than violent crime sentences, and so taking a headcount of prisoners artificially increases the appearance of violent incarceration simply because those criminals spent more time in jail. Here’s how Alexander wrote about this in her book:

Murder convictions tend to receive a tremendous amount of media attention, which feeds the public sense that violent crime is rampant and forever on the rise, but like violent crime in general, the murder rate cannot explain the growth of the penal apparatus. Homicide convictions account for a tiny fraction of the growth in prison population. In the federal system, for example, homicide offenders account for 0.4% of the past decades’ growth in the federal prison population white drug offenders account for nearly 61% of that expansion. In the state system, less than 3% of new court commitments to state prison typically involve people convicted of homicide. As much as half prisoners are violent offenders, but that statistic can easily be misinterpreted. Violent offenders tend to get longer prison sentences than non-violent offenders, and therefore comprise a much larger share of the prison population than they would if they had earlier release dates.

Latzer also makes another claim that–while technically true–is misleading. And this one was also anticipated and rebutted by Alexander. He says:

Critics of “mass incarceration” often point to the federal prisons, where half of inmates, or about 96,000 people, are drug offenders. But 99.5% of them are traffickers. The notion that prisons are filled with young pot smokers, harmless victims of aggressive prosecution, is patently false.

The problem with this one is that prosecutors have incredibly wide discretion in which charges to bring against people and, on top of that, have virtually zero oversight in how they exercise that discretion. Writing in The New Jim Crow, Alexander points out that:

The risk that prosecutorial discretion will be racially biased is especially acute in the drug enforcement context , where virtually identical behavior is susceptible to a wide variety of interpretations and responses and the media imagery and political discourse has been so thoroughly racialized. Whether a kid is perceived as a dangerous, drug-dealing thug or instead is viewed as a good kid who was merely experimenting with drugs and selling to a few of his friends, has to do with the ways information about illegal drug activity is processed and interpreted in a social climate in which drug dealing is racially defined.

In other words, the exact same behavior (selling drugs) could easily lead to a simple possession charge for some people and a trafficking charge for others. We can’t just blithely assume that whatever charge a person ends up serving time for reflects accurately and fairly on what they did and what someone else did not do.

This is not to say that Latzer doesn’t make any valid point at all. He does. He points out that blacks are more likely than whites to commit violent crime. This is true, and in fact it’s a point that Alexander concedes in her book. So, if you’re focused on violent crime, there is a basis to say that the criminal justice system is fair: there are more blacks behind bars because more blacks commit violent crimes.

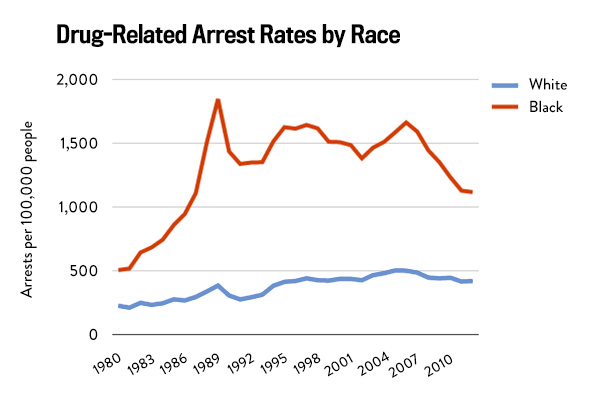

On the other hand, if you’re looking at drug crimes, then there is a basis to say that the criminal just system is not fair. Blacks and whites use illegal drugs at roughly the same rates, but blacks are far, far more likely to face arrest, prosecution, and conviction than whites, as this chart (from Slate) illustrates:

But, even in the case of violent crime, there is fairly clear evidence of racism. Many studies have found that the justice system is fairly unbiased when it comes to the race of perpetrators of violent crime, but it is very, very biased when it comes to the race of victims of violent crime. In short, if you kill a black person then (whether you are white or black) your sentence will be relatively low. But if you kill a white person then (whether your are white or black) your sentence will be relatively high. Based purely on the data, one would say that our criminal justice system believes that all lives matter, but some lives matter more.

I’ve been planning a long post / review of The New Jim Crow for some time now, but I haven’t finished organizing my quotes and notes yet. So you can consider this a preview. And, along those lines, I’ll make one more point: the effects of conviction are far, far more general than the question of incarceration. This isn’t really a criticism of Latzer. He focused on incarceration, and so this falls outside the scope of his argument. But it’s something important for us to keep in mind. First, you don’t have to go to jail at all to get a felony conviction on your record. Second, that felony conviction is going to stay on your record long after you have “served your debt to society.” If the criminal justice system is unfair, it’s not just about incarceration. It’s about losing the right to vote. It’s about losing access to government programs like student loans or food stamps. It’s about the government banning your friends and family from supporting you (if they live in public housing) when you get out. And–most egregiously of all–it’s about a scarlet-F that will follow you to every job interview and ensure that long after you are outside the prison walls you are still practically barred from building a new life for yourself.

There’s lot at stake here, folks, and it’s not just about violent crime.