Last month, Nathaniel penned a critique of criminal justice scholar Barry Latzer’s WSJ piece on the supposed “myth” of mass incarceration. The impact of the war on drugs tends to be minimized by counting the amount of drug offenders vs. violent criminals in the prison population (hint: there are more of the latter). In his critique, Nathaniel wrote, “Drug sentences are generally shorter than violent crime sentences, and so taking a headcount of prisoners artificially increases the appearance of violent incarceration simply because those criminals spent more time in jail.” This, of course, was noted by Michelle Alexander in her book The New Jim Crow. But what do the data say? According to Brooking’s Jonathan Rothwell,

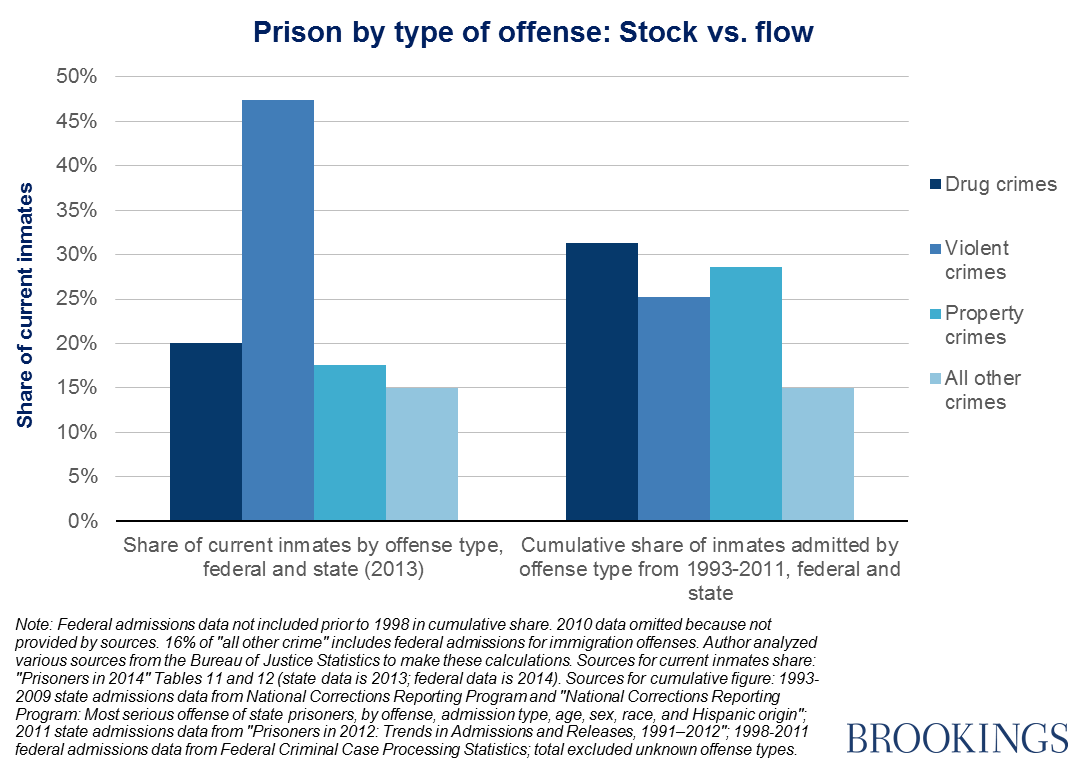

There is no disputing that incarceration for property and violent crimes is of huge importance to America’s prison population, but the standard analysis—including Alexander’s critics—fails to distinguish between the stock and flow of drug crime-related incarceration. In fact, there are two ways of looking at the prison population as it relates to drug crimes:

- How many people experience incarceration as a result of a drug-related crime over a certain time period?

- What proportion of the prison population at a particular moment in time was imprisoned for a drug-related crime?

The answers will differ because the length of sentences varies by the kind of crime committed. As of 2009, the median incarceration time at state facilities for drug offenses was 14 months, exactly half the time for violent crimes. Those convicted of murder served terms of roughly 10 times greater length.

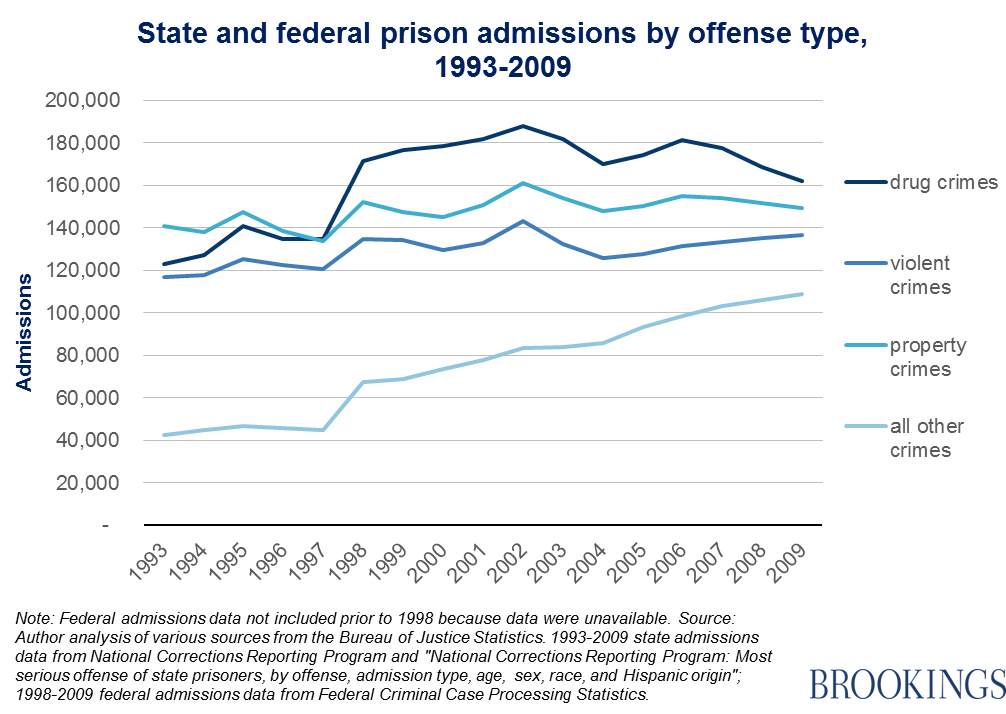

The picture is clear: Drug crimes have been the predominant reason for new admissions into state and federal prisons in recent decades.[ref]This is the finding of the National Academy of Sciences as well.[/ref] In every year from 1993 to 2009, more people were admitted for drug crimes than violent crimes. In the 2000s, the flow of incarceration for drug crimes exceeded admissions for property crimes each year. Nearly one-third of total prison admissions over this period were for drug crimes:

In short, Alexander was right when she saw drug prosecution as “a big part of the mass incarceration story.” It turns out “drug crimes account for more of the total number of admissions in recent years—almost one third (31 percent), while violent crimes account for one quarter:”

As Nathaniel concluded,

First, you don’t have to go to jail at all to get a felony conviction on your record. Second, that felony conviction is going to stay on your record long after you have “served your debt to society.” If the criminal justice system is unfair, it’s not just about incarceration. It’s about losing the right to vote. It’s about losing access to government programs like student loans or food stamps. It’s about the government banning your friends and family from supporting you (if they live in public housing) when you get out. And–most egregiously of all–it’s about a scarlet-F that will follow you to every job interview and ensure that long after you are outside the prison walls you are still practically barred from building a new life for yourself.

There’s lot at stake here, folks, and it’s not just about violent crime.