I recently reread a 2014 Forbes article by GMU law professor Todd Zywicki and former Fed economist Thomas Durkin based on their Oxford-published Consumer Credit and the American Economy and thought it was worth sharing. The authors explain that despite the claims of people like Elizabeth Warren,

economists have long understood why consumers borrow. Although there are exceptions to any rule, for most it bears little resemblance to Senator Warren’s picture of hapless victims goaded into debt by rapacious credit card issuers. Instead, consumers borrow for essentially the same reasons that businesses borrow: for capital investments and to smooth disruptions in income and expenses. And paternalistic regulations that make credit more expensive and less available typically makes people poorer.

Zywicki and Durkin use the example of a washing machine:

A washing machine is no frivolous bauble; its value is in not having to schlep to the laundromat every Saturday with a pocket full of quarters. While a washing machine costs much more on the front end to acquire, it generates a stream of benefits over years. In that sense, it is no different from a construction company that borrows money to purchase a backhoe to dig a ditch instead of hiring ten guys with shovels.

The “hand-wringing about how other people use consumer debt is as old as debt itself. For example, the New York Times warned in the 70s that American consumers were “borrowing trouble”—the 1870s, that is.” They point out that

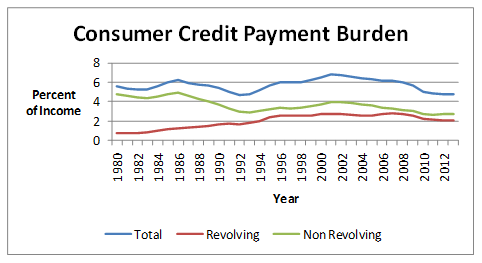

40 years ago if you needed $400 for a car repair, you would visit your bank, credit union, or a local personal finance company for a loan to be repaid over 12-24 months. If you bought a refrigerator or new bedroom set, you would finance it through the appliance store or department store and repay it “on time.” Today, you likely would just put it on your credit card. In fact, even despite the astonishing surge of student loan debt over the past two decades (it now exceeds credit card debt), the non-mortgage debt repayment obligation as a share of income is actually lower today for the typical household, including the typical low-income household, than in 1980 (see chart below).

Finally,

while well-designed regulation can improve competition and consumer choice, economic history demonstrates that heavy-handed regulations that restrict product offerings frequently harm their intended beneficiaries. For example, who uses payday lending? Those who don’t have access to credit cards or would max out their cards if they used them. So what happens when well-intentioned regulators take away payday lending? Many payday lending customers shift to other alternatives, such as bank overdraft protection or pawnbrokers, which are often even more expensive. Eliminating options for low-income consumers (especially those options that they are actually using) doesn’t eliminate their need for credit.

The whole article is worth reading. Check it out.