This is part of the DR Book Collection.

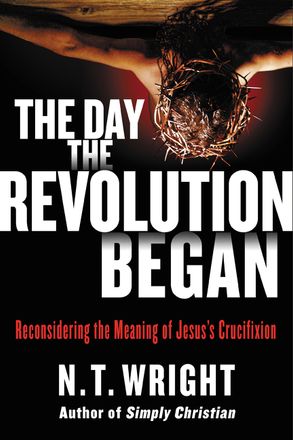

I’ve been a fan of New Testament scholar N.T. Wright’s work for the last several years. His Surprised by Hope even earned a much-coveted spot among my Honorable Mentions on my Most Influential Books list a couple years ago. His popular works have a way of reaching all audiences with insightful, erudite scholarship. His newest book–The Day the Revolution Began: Reconsidering the Meaning of Jesus’s Crucifixion–is no different. Mormons have had an uneasy relationship with the symbol of the cross, which is odd when one considers how frequently it is mentioned in the Book of Mormon (e.g., 1 Ne. 11:33, Jacob 1:8, 2 Ne. 9:18, 3 Ne. 27:14-15, Ether 4:1). Some of our atonement theories adopt a pseudo-scientific framework in order to work out the mechanics of what we call The Atonement. Unfortunately, our understanding of the Atonement is often divorced from the context of scripture. For example, we often fail to recognize that the terms atonement, redemption, and salvation have very different meanings and contexts within scripture: priestly/cultic, kinship, political/martial. Wright attempts to place Christ’s crucifixion within the broader context of Israel’s covenant and deliverance and ultimately the grand narrative of creation itself.

I’ve been a fan of New Testament scholar N.T. Wright’s work for the last several years. His Surprised by Hope even earned a much-coveted spot among my Honorable Mentions on my Most Influential Books list a couple years ago. His popular works have a way of reaching all audiences with insightful, erudite scholarship. His newest book–The Day the Revolution Began: Reconsidering the Meaning of Jesus’s Crucifixion–is no different. Mormons have had an uneasy relationship with the symbol of the cross, which is odd when one considers how frequently it is mentioned in the Book of Mormon (e.g., 1 Ne. 11:33, Jacob 1:8, 2 Ne. 9:18, 3 Ne. 27:14-15, Ether 4:1). Some of our atonement theories adopt a pseudo-scientific framework in order to work out the mechanics of what we call The Atonement. Unfortunately, our understanding of the Atonement is often divorced from the context of scripture. For example, we often fail to recognize that the terms atonement, redemption, and salvation have very different meanings and contexts within scripture: priestly/cultic, kinship, political/martial. Wright attempts to place Christ’s crucifixion within the broader context of Israel’s covenant and deliverance and ultimately the grand narrative of creation itself.

In Wright’s view, Jesus’ sacrifice is too often transformed into a reductive “works-contract” theory in which Jesus takes the punishment for our sins so that we can go to heaven. In short, Christians have reduced the Atonement to merely address personal morality (important, but not the whole story) and in turn have cast Israel’s God as a pagan deity that requires punishment and sacrifice in order for us to enter into a Platonized afterlife. So what is it really about? Wright explains,

First, it seems clear to me that once we replace the common vision of Christian hope (“going to heaven”) with the biblical vision of “new heavens and new earth,” there will be direct consequences for how we understand both the human problem and the divine solution. Second, in the usual model, what stops us from “going to heaven” is sin, and sin is dealt with (somehow) on the cross. In the biblical model, what stops us from being genuine humans (bearing the divine image, acting as the “royal priesthood”) is not only sin, but the idolatry that underlies it. The idols have gained power, the power humans ought to be exercising in God’s world; idolatrous humans have handed it over to them. What is required, for God’s new world and for renewed humans within it is for the power of the idols to be broken. Since sin, the consequence of idolatry, is what keeps human in thrall to the nongods of the world, dealing with sin has a more profound effect than simply releasing humans to go to heaven. It releases humans from the grip of the idols, so they can worship the living God and be renewed according to his image…In the Bible, God’s plan to deal with sin, and so to break the power of idols and bring new creation to his world, is focused on the people of Israel. In the New Testament, this focus is narrowed to Israel’s representative, the Messiah. He stands in for Israel and so fulfills the divine plan to restore creation itself. [ref]Wright, The Day the Revolution Began. Kindle ed.[/ref]

For Wright, the fall of Adam and Eve was their failure to fulfill their vocation as God’s image-bearers in the world. The covenant with Abram (Abraham) established his family (the eventual nation of Israel) as the vehicle by which creation would be set right. Yet, Israel also failed in their vocation and experienced exile just as their primal parents. However, God was faithful to his covenant with Israel despite their faithlessness. It was through Jesus–Israel’s true representative–that the covenant was fulfilled and the curse (for example, see Deut. 30:15-20) of exile, condemnation, and death was exhausted. Through the cross, idolatry, the “principalities…powers…the rulers of the darkness of this world [and] spiritual wickedness in high places” (Eph. 6:12), were defeated.

The book is theologically rich and thought-provoking. Check out Wright’s lectures on the subject at Pepperdine University below: