In the most recent issue of Nature Human Behaviour, neuroscientist Molly Crockett suggests that “digital media may exacerbate the expression of moral outrage by inflating its triggering stimuli, reducing some of its costs and amplifying many of its personal benefits.”

She explains,

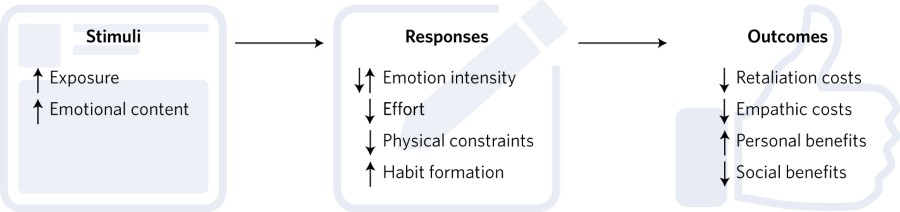

A recent study conducted in the US and Canada suggests that encountering norm violations in person is relatively rare: less than 5% of reported daily experiences involved directly witnessing or experiencing immoral acts. But the internet exposes us to a vast array of misdeeds, from corrupt practices of bankers on Wall Street, to child trafficking in Asia, to genocide in Africa — the list goes on. In fact, data from a study of everyday moral experience show that people are more likely to learn about immoral acts online than in person or through traditional forms of media…Research on virality shows that people are more likely to share content that elicits moral emotions such as outrage. Because outrageous content generates more revenue through viral sharing, natural selection-like forces may favour ‘supernormal’ stimuli that trigger much stronger outrage responses than do transgressions we typically encounter in everyday life. Supporting this hypothesis, there is evidence that immoral acts encountered online incite stronger moral outrage than immoral acts encountered in person or via traditional forms of media…These observations suggest that digital media transforms moral outrage by changing both the nature and prevalence of the stimuli that trigger it. The architecture of the attention economy creates a steady flow of outrageous ‘clickbait’ that people can access anywhere and at any time.

This could be a problem:

By increasing the frequency and extremity of triggering stimuli, one possible long-term consequence of digital media is ‘outrage fatigue’: constant exposure to outrageous news could diminish the overall intensity of outrage experiences, or cause people to experience outrage more selectively to reduce emotional and attentional demands. On the other hand, studies have shown that venting anger begets more anger. If digital media makes it easier to express outrage, this could intensify subsequent experiences of outrage. Future research is necessary to resolve these possibilities…[Online], people can express outrage online with just a few keystrokes, from the comfort of their bedrooms, either directly to the wrongdoer or to a broader audience. With even less effort, people can repost or react to others’ angry comments. Since the tools for easily and quickly expressing outrage online are literally at our fingertips, a person’s threshold for expressing outrage is probably lower online than offline…And just as a habitual snacker eats without feeling hungry, a habitual online shamer might express outrage without actually feeling outraged. Thus, when outrage expression moves online it becomes more readily available, requires less effort, and is reinforced on a schedule that maximizes the likelihood of future outrage expression in ways that might divorce the feeling of outrage from its behavioural expression.

So why the outrage?

[E]xpressing moral outrage benefits individuals by signalling their moral quality to others. That is, outrage expression provides reputational rewards. People are not necessarily conscious of these rewards when they express outrage. But the fact that people are more likely to punish when others are watching indicates that a concern for reputation at least implicitly whets our appetite for moral outrage. Of course, online social networks massively amplify the reputational benefits of outrage expression. While offline punishment signals your virtue only to whoever might be watching, doing so online instantly advertises your character to your entire social network and beyond. A single tweet with an initial audience of just a few hundred can quickly reach millions through viral sharing — and outrage fuels virality.

And while this outrage may “benefit society by holding bad actors accountable and sending a message to others that such behaviour is socially unacceptable,” for the most part

moral disapproval ricochets within echo chambers but only occasionally escapes. Second, by lowering the threshold for outrage expression, digital media may degrade the ability of outrage to distinguish the truly heinous from the merely disagreeable. Third, expressing outrage online may result in less meaningful involvement in social causes, for example through volunteering or donations. People are less likely to spend money on punishing unfairness when they are given the opportunity to express their outrage via written messages instead. Finally, there is a serious risk that moral outrage in the digital age will deepen social divides. A recent study suggests a desire to punish others makes them seem less human. Thus, if digital media exacerbates moral outrage, in doing so it may increase social polarization by further dehumanizing the targets of outrage.

She concludes,

The framework proposed here offers a set of testable hypotheses about the impact of digital media on the expression of moral outrage and its social consequences…Preliminary data support the framework’s predictions, showing that outrage-inducing content appears to be more prevalent and potent online than offline. Future studies should investigate the extent to which digital media platforms intensify moral emotions, promote habit formation, suppress productive social discourse, and change the nature of moral outrage itself. There are vast troves of data that are directly pertinent to these questions, but not all of it is publicly available. These data can and should be used to understand how new technologies might transform ancient social emotions from a force for collective good into a tool for collective self-destruction.

Lay off the outrage porn.