Harvard’s Lant Pritchett has an incredible new paper out that looks at the best course for eliminating global poverty:

So think of two ways to help the global poor. One is for rich people (in a global sense) to give a dollar and get roughly a dollar’s worth of benefits for the poor. The other people is for rich people to allow people who would like to work at the prevailing wage of their country to do so and not deploy active coercion to prevent this—which reflects the person’s contribution to product and hence is (or can be made to be) zero net cost to the host country. Of course, a dollar for a poor person could produce vastly more human well-being than had the richer person spent the money as the marginal utility was much, much higher for the poor person, but this redistribution effect is the same for both options. This means, at least in current conditions, the least you can do—just increasing the freedom of people who want to work and people who want those people to work to carry out that mutually beneficially transaction across national borders—is better than the best you can do of trying to directly help people in poverty but without allowing them to move to opportunity (pg. 1-2).

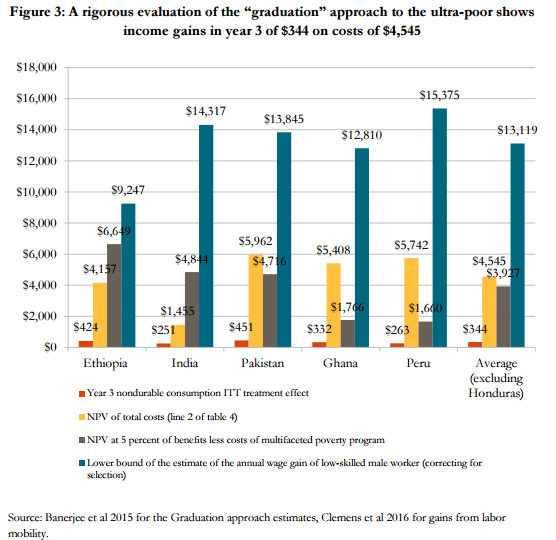

Pritchett looks at the Ultra Poor Graduation program, whose stated claim is “to graduate ultra poor households out of extreme poverty to a more stable state. This 24-month program provides beneficiaries with a holistic set of services including: livelihood trainings, productive asset transfers, consumption support, savings plans, and healthcare” (pg. 9). Pritchett finds that this program led to an average income gain of $344 dollars by the third year for targeted households. “The five country average NPV of costs per household of the 24 month program was $4,545” (pg. 9).

While Pritchett recognizes that redistribution can indeed benefit the poor, its impact is quite small. He concludes,

A large part of the explanation of differences in labor productivity across countries is differences in “A”—total factor productivity. Transmitting A from country to country has proven difficult. This implies that labor with the exact same intrinsic productivity will have much higher productivity (and hence justify a higher wage) in a high A than in a low A country. But, by and large, rich countries have passed extraordinarily strict regulations on the movement of unskilled labor. A relaxation of these restrictions could produce the largest single gains in global poverty of any available policy, program or project action. And since these gains to movers are (mostly) due to higher A which (at the margin) is a “public good” (it is non-rival and non-excludable) in the host country these gains are essentially free to the host country (or could be free to the host country under some technical design conditions).

Comparing the annual gains of the Ultra Poor Graduation program ($344 per household for a cost of $4,545) to those of a low-skill worker simply moving to and working in the United States ($17,115), Pritchett finds that the Ultra Poor Graduation program would have to invest $226,000 per person in order to match the gains of migration. Furthermore,

sustained rapid economic growth in developing countries—that is sustained by improvements in A—can also produce cumulatively enormous gains. And avoiding growth collapses/stagnation can prevent enormous losses. So, even though traditional measures of the country to country transfers of resources via “foreign aid” do not, in and of themselves, appear to be responsible for producing most of the observed differences in economic growth, investments that could bring that about more sustained growth (both more sustained accelerations and fewer sharp and extended decelerations) could also have astronomical returns.

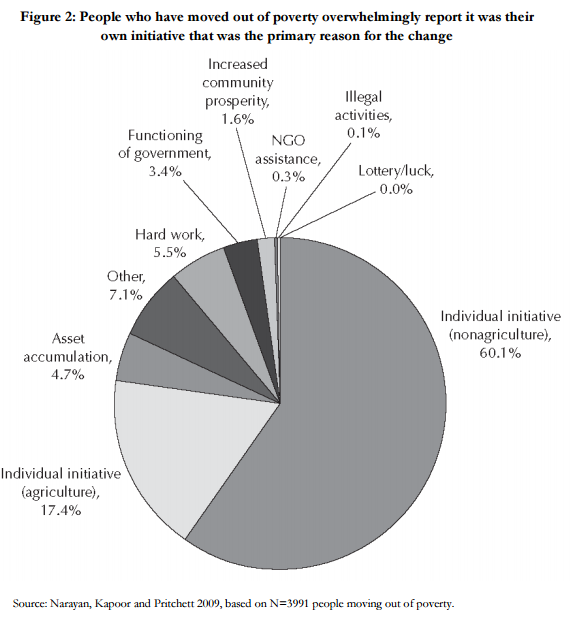

As Bryan Caplan sums it up, “Virtually all poverty reduction comes from economic growth and migration – not redistribution or philanthropy.”