Michael Cox and Richard Alm of SMU’s O’Neil Center have an essay in D Magazine based on the latest report from the Center. The two

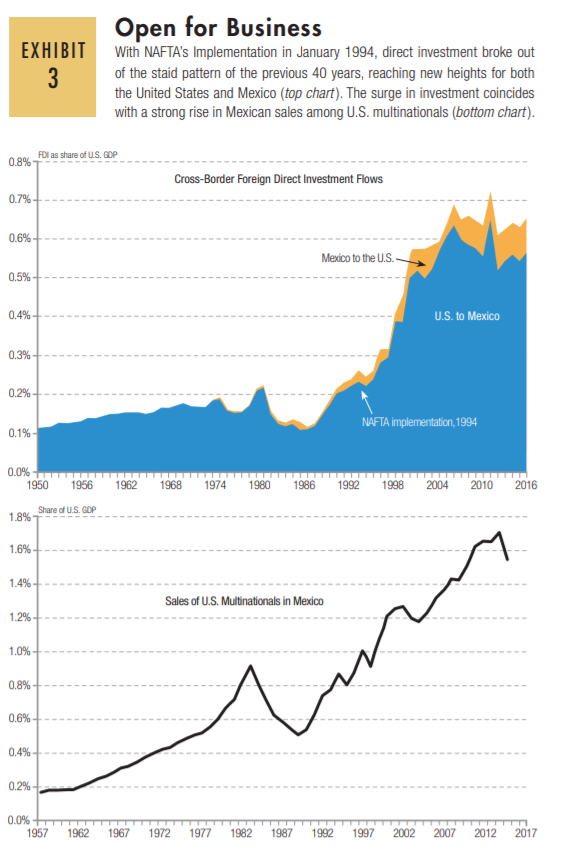

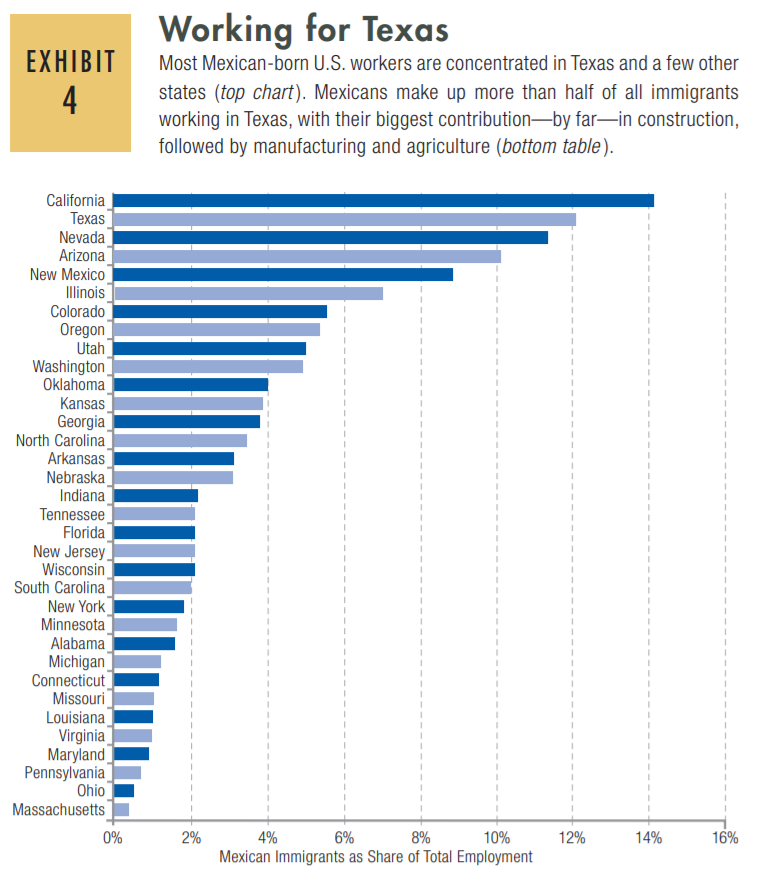

imagine Texas and Mexico as one economy, connected by exports, imports, migration, cross-border business investments, transport infrastructure, tourism, and knowledge transfers. As a combined economy, Texas and Mexico churn out an annual GDP of more than $4 trillion, enough to rank as the world’s sixth-largest economy, just behind Germany and ahead of Russia.

We denote this sprawling and diverse economy by the portmanteau word: Texico. The name captures the reality that over the past quarter-century the Texas and Mexico economies have emerged as highly integrated, making an often-unsung contribution to Texas’ reign as America’s top-performing state economy.

The explain how trade has deeply integrated the two countries:

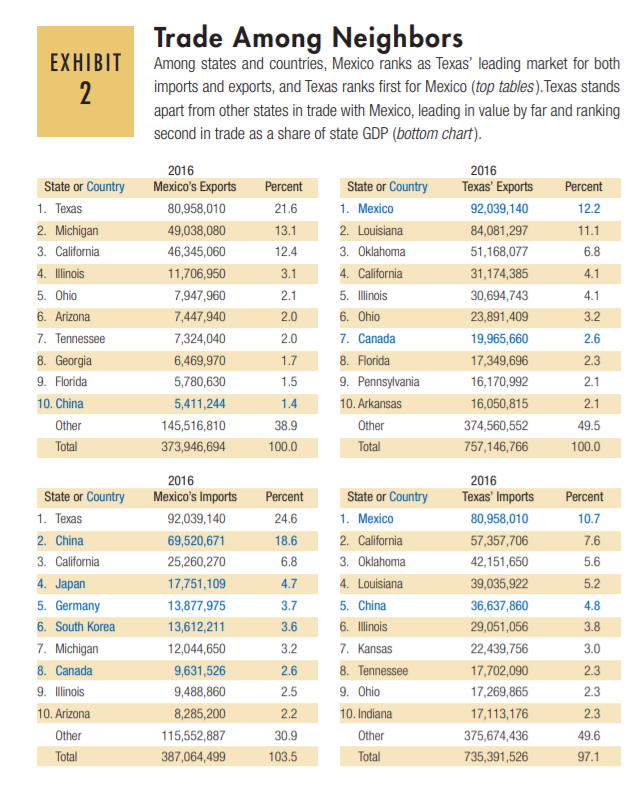

An often-cited gauge of integration is trade—exports moving south, imports moving north. They totaled $188 billion last year, or more than 11 percent of gross state product, separating Texas from all other states in doing business with Mexico.

Texas companies are finding business opportunities in Mexico—among them, cosmetics-maker Mary Kay Inc. and telecommunications giant AT&T Inc., both based in Dallas-Fort Worth. At the same time, Mexican companies are heading northward and expanding their businesses, including Mission Foods in Irving and the movie theater chain Cinépolis in Addison.

The Texas and Mexico economies are more formidable combined rather than separate. Binational supply chains, for example, take advantage of low production costs in Mexico and highly skilled professional labor in Texas. The companies emerge more competitive in the global marketplace, able to sell their wares at a better price.

Automobile production comes to mind—for good reason. Plants in the Dallas-Fort Worth area are on the northern edge of the Texas-Mexico Automotive SuperCluster region, which includes close to 30 assembly plants and more than 230 parts suppliers in Texas and Mexico’s northern states.

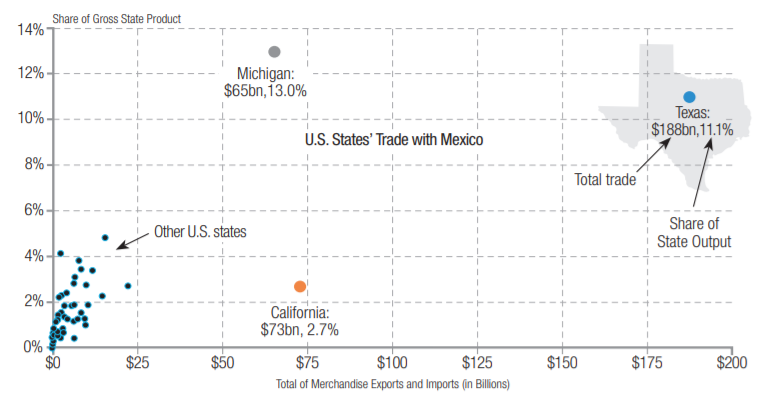

Texas and Mexico have already profited a great deal from their binational economy, even though work began in earnest only recently. Mexico didn’t open its energy and telecom markets until just a few years ago. During negotiations that led to the North American Free Trade Agreement, Mexico clung to its monopolies in these industries. With its oil output falling, Mexico finally lifted its ban on foreign oil and gas companies three years ago. If all goes well, this should be a bonanza for Texas, with its deep roster of oilfield services and exploration companies. The telecom monopoly expired about the same time—and AT&T rushed in with its wireless service.

The annual report provides a few more interesting insights:

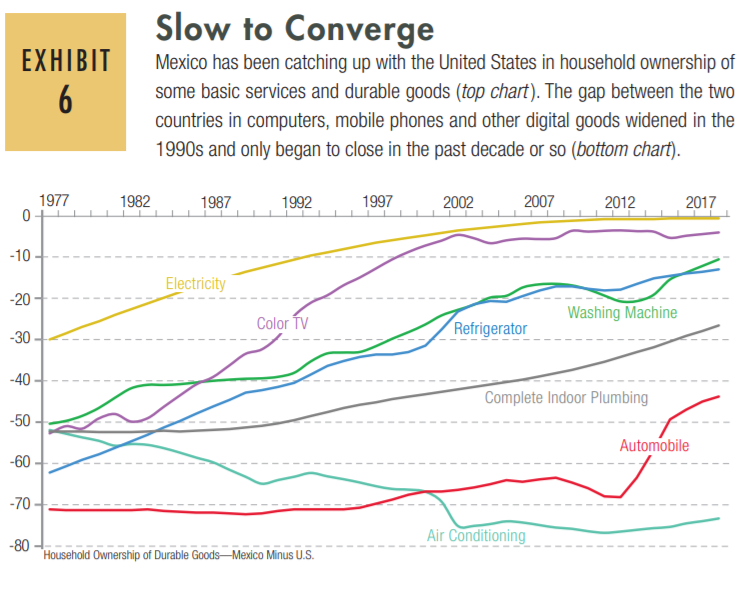

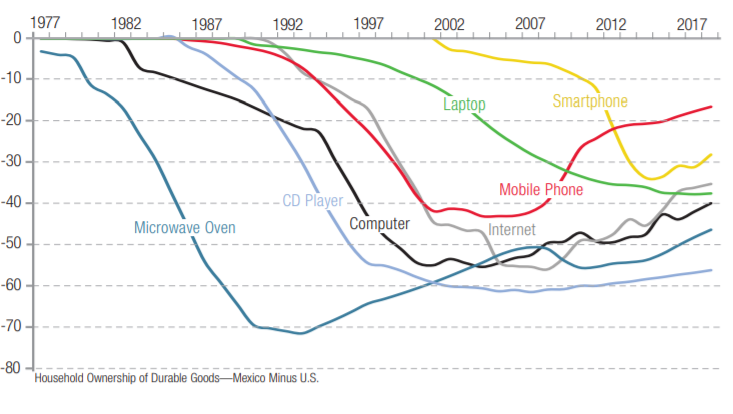

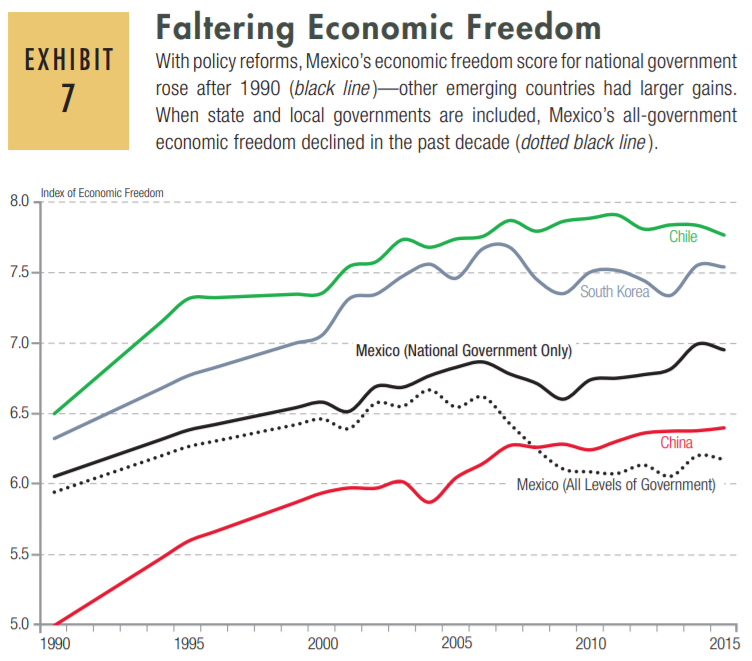

The report explains the slow convergence above: “Other factors like low levels of education shouldn’t be ignored, but the ongoing plague of corruption, cronyism and rising violence go a long way toward explaining why Mexican growth and income haven’t converged with the United States or kept pace with the likes of Chile, South Korea and China” (pg. 13).

Cox and Alm conclude,

Texans are well aware of Mexico’s shortcomings, including corruption and drug-cartel violence. None of these problems will get any better by enacting policies that build barriers against Mexico and harm the Texas and Mexico economies. Perhaps Trump and Obrador will decide that the best course lies in expedient practicality—recognizing the fact that Texico has been working and building a large constituency. If these two leaders don’t make a mess of things, the businesses of Texas and Mexico can take it from there.