From a recent NBER Digest:

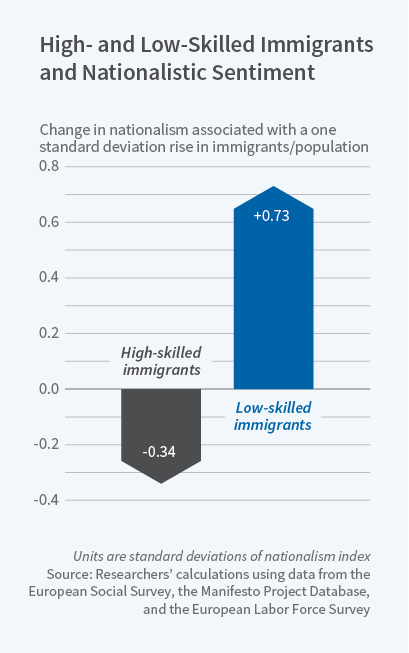

In Skill of Immigrants and Vote of the Natives: Immigration and Nationalism in European Elections 2007-16 (NBER Working Paper No. 25077), Simone Moriconi, Giovanni Peri, and Riccardo Turati explore the relationship between immigration and European elections. They develop an index of “nationalistic” attitudes of political parties to measure the shift in preferences among voters when confronted with influxes of skilled and unskilled immigrants. They find that larger inflows of highly educated immigrants dampen nationalistic sentiments, while larger inflows of less-educated immigrants heighten them. Their results imply that a more balanced inflow of high-skilled and low-skilled immigrants could attenuate voters’ nationalistic attitudes.

...The new study tracks voter attitudes and behavior for all political parties and elections in 12 European countries for a decade. It relies on demographic and political data from the European Social Survey and a number of other sources. In addition, the researchers collected and classified the political manifestos of 126 parties for 28 elections, focusing in particular on how frequently these materials mentioned nationalistic subjects, the European Union, and other indicators of where parties stood on the political spectrum.

The researchers found “that highly educated native voters are less nationalistic in their attitudes towards immigrants than less-educated natives. The data also show strong nationalistic sentiments in regional pockets in the United Kingdom, Ireland, France, Germany, Demark, Sweden, Norway and, especially, Italy.”

The results suggest that a 1 percent increase in the share of a country’s population who are immigrants in highly educated, highly skilled groups was associated with a 0.1 standard deviation voting change away from nationalism. An increase of comparable size in the number of less-educated and lower-skilled immigrants led to a 0.12 standard deviation voting change towards nationalism. The same patterns emerged when the researchers analyzed voter sentiment expressed in surveys. In this case, a 1 percent increase in high-skilled immigrants led to a 0.07 standard deviation decrease away from nationalism, while a 1 percent increase in lower-skilled immigrants lead to a 0.07 standard deviation increase in nationalism. The results were broadly similar regardless of whether the analysis focused on all immigrants or only on immigrants from non-EU nations.

Immigration is not only about ethnicity, but class as well.