In theory, setting goals should be simple. Start with where you are by measuring your current performance. Decide where you want to be. Then map out a series of goals that will get you from Point A to Point B with incremental improvements. Despite the simple theory, my lived reality was a nightmare of failure and self-reproach.

It took decades and ultimately I fell into the solution more by accident than by design, but I’m at a point now where setting goals feels easy and empowering. Since I know a lot of people struggle with this—and maybe some even struggle in the same ways that I did—I thought I’d write up my thoughts to make the path a little easier for the next person.

The first thing I had to learn was humility.

For most of my life, I set goals by imagining where I should be and then making that my goal. I utterly refused to begin with where I currently was. I refused to even contemplate it. Why? Because I was proud, and pride always hides insecurity. I could accept that I wasn’t where I should be in a fuzzy, abstract sense. That was the point of setting the goal in the first place. But to actually measure my current achievement and then use that as the starting point? That required me to look in the mirror head-on, and I couldn’t bear to do it. I was too afraid of what I’d see. My sense of worth depended on my achievement, and so if my achievements were not what they should be then I wasn’t what I should be. The first step of goal setting literally felt like an existential threat.

This was particularly true because goal-setting is an integral part of Latter-day Saint culture. Or theology. The line is fuzzy. Either way, the worst experiences I had with goal setting were on my mission. The stakes felt incredibly high. I was the kind of LDS kid who always wanted to go on a mission. I grew up on stories of my dad’s mission and other mission stories. And I knew that being a mission was like this singular opportunity to prove myself. So on top of the general religious pressure there was this additional pressure of “now or never”. If I wasn’t a good missionary, I’d regret it for the rest of my life. Maybe for all eternity. No pressure.

So when we had religious leaders come and say things like, “If you all contact at least 10 people a day, baptisms in the mission will double,” I was primed for an entirely dysfunctional and traumatizing experience. Which is exactly what I get.

(I’m going to set aside the whole metrics-approach-to-missionary-work conversation, because that’s a topic unto itself.)

I tried to be obedient. I set the goal. And I recorded my results. I think I maybe hit 10 people a day once. Certainly never for a whole week straight (we planned weekly). When I failed to hit the goal, I prayed and I fasted and I agonized and I beat myself up. But I never once—not once!—just started with my total from last week and tried to do an incremental improvement on that. That would mean accepting that the numbers from last week were not some transitory fluke. They were my actual current status. I couldn’t bear to face that.

This is one of life’s weird little contradictions. To improve yourself—in other words, to change away from who you currently are—the first step is to accept who you currently are. Accepting reality—not accepting that its good enough, but just that it is—will paradoxically make it much easier to change reality.

Another one of life’s little paradoxes is that pride breeds insecurity and humility breeds confidence. Or maybe it’s the other way around. When I was a missionary at age 19-21, I still didn’t really believe that I was a child of God. That I had divine worth. That God loved me because I was me. I thought I had to earn worth. I didn’t realize it was a gift. That insecurity fueled pride as a coping mechanism. I wanted to be loved and valuable. I thought those things depended on being good enough. So I had to think of myself as good enough.

But once I really accepted that my value is innate—as it is for all of us—that confidence meant I no longer had to keep up an appearance of competence and accomplishment for the sake of protecting my ego. Because I had no ego left to protect.

Well, not no ego. It’s a process. I’m not perfectly humble yet. But I’m getting there, and that confidence/humility has made it possible for me to just look in the mirror and accept where I am today.

The second thing is a lot simpler: keeping records.

The whole goal setting process as I’ve outlined it depends on being able to measure something. This is why I say I sort of stumbled into all of this by accident. The first time I really set good goals and stuck to them was when I was training for my first half marathon. Because it wasn’t a religious goal, the stakes were a lot lower, so I didn’t have a problem accepting my starting point.

More importantly, I was in the habit of logging my miles for every run. So I could look back for a few weeks (I’d just started) and easily see how many miles per week I’d been running. This made my starting point unambiguous.

Next, I looked up some training plans. These showed how many miles per week I should be running before the marathon. They also had weekly plans, but to make the goals personal to me, I modified a weekly plan so that it started with my current miles-per-week and ramped up gradually in the time I had to the goal mies-per-week.

I didn’t recognize this breakthrough for what it was at the time, but—without even thinking about it—I started doing a similar thing with other goals. I tracked my words when I wrote, for example, and that was how I had some confidence that I could do the Great Challenge. I signed up to write a short story every week for 52 weeks in a year because I knew I’d been averaging about 20,000 words / month, which was within range of 4-5 short stories / month.

And then, just a month ago, I plotted out how long I wanted it to take for me to get through the Book of Mormon attribution project I’m working on. I’ve started that project at least 3 or 4 times, but never gotten through 2 Nephi, mostly because I didn’t have a road map. So I built a road map, using exactly the same method that I used for the running plan and the short stories plan.

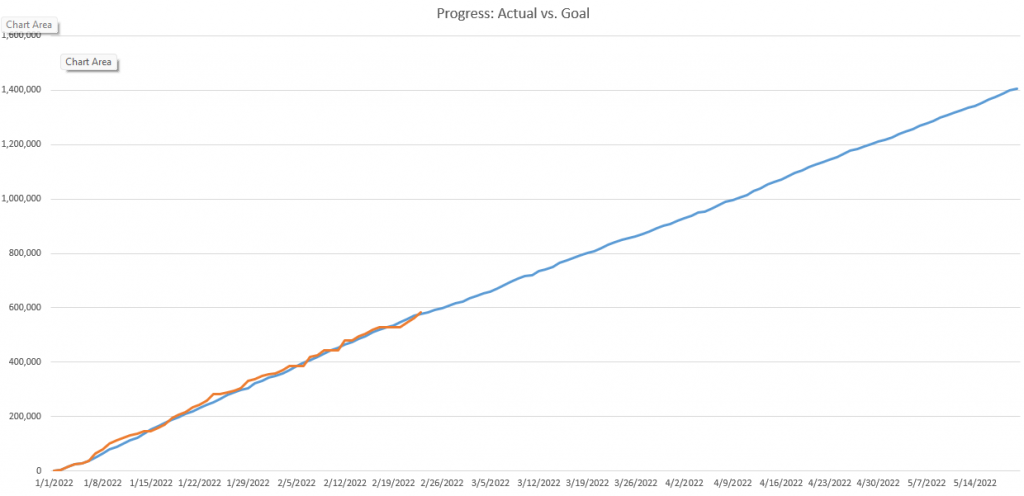

And that was when I finally realized I was doing what I’d wanted to do my whole life: setting goals. Setting achievable goals. And then achieving them. Here’s my chart for the Book of Mormon attribution project, by the way, showing that I’m basically on track about 2 months in.

I hope this helps someone out there. It’s pretty basic, but it’s what I needed to learn to be able to start setting goals. And setting goals has enabled me to do two things that I really care about. First, it lets me take on bigger projects and improve myself more / faster than I had in the past. Second, and probably more importantly, it quiets the demon of self-doubt. Like I said: I’m not totally recovered from that “I’m only worth what I accomplish” mental trap. When I look at my goals and see that I’m making consistent progress towards things I care about, it reminds me what really matters. Which is the journey.

I guess that’s the last of life’s little paradoxes for this blog post: you have to care about pursuing your goals to live a meaningful, fulfilling life. But you don’t actually have to accomplish anything. Accomplishment is usually outside your control. It’s always subject to fortune. The output is the destination. It doesn’t really matter.

But you still have to really try to get that output. Really make a journey towards that destination. Because that’s the input. That’s what you put in. That does depend on you.

I believe that doing my best to put everything into my life is what will make my life fulfilling. What I get out of it? Well, after I’ve done all I can, then who cares how it actually works out. That’s in God’s hands.