Part 1: Anti-Americanism Americanism

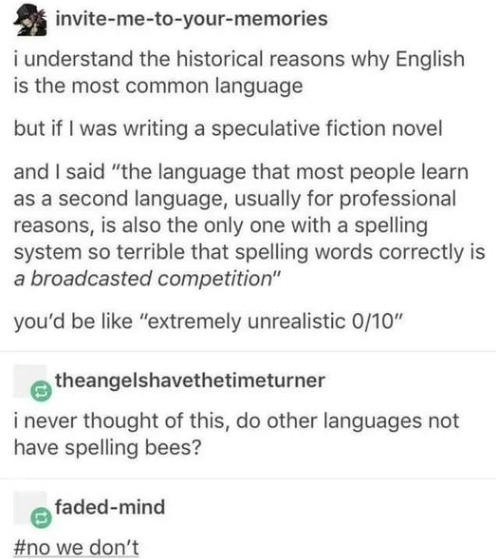

I ran across a humorous meme in a Facebook group that got me thinking about anti-provincial provincialism. Well, not the meme, but a response to it. Here’s the original meme:

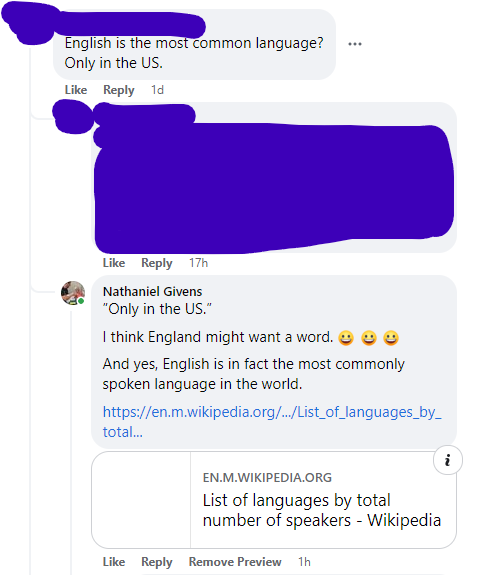

Now check out this (anonymized) response to it (and my response to them):

What has to happen, I wondered, for someone to assert that English is the most common language “only in the United States“? Well, they have to be operating from a kind of anti-Americanism that is so potent it has managed to swing all the way around back to being an extreme American centrism view again. After all, this person was so eager to take the US down a peg (I am assuming) that they managed to inadvertently erase the entire Anglosphere. The only people who exclude entire categories of countries from consideration are rabid America Firsters and rabid America Lasters. The commonality? They’re both only thinking about America.

It is a strange feature of our times that so many folks seem to become the thing they claim to oppose. The horseshoe theory is having its day.

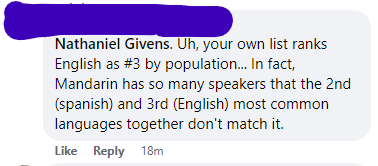

The conversation got even stranger when someone else showed up to tell me that I’d misread the Wikipedia article that I’d linked. Full disclosure: I did double check this before I linked to it, but I still had an “uh oh” moment when I read their comment. Wouldn’t be the first time I totally misread a table, even when specifically checking my work. Here’s the comment:

Thankfully, dear reader, I did not have to type out the mea culpa I was already composing in my mind. Here’s the data (and a link):

My critic had decided to focus only on the first language (L1) category. The original point about “most commonly spoken” made no such distinction. So why rely on it? Same reason, I surmise, as the “only in the US” line of argument: to reflexively oppose anything with the appearance of American jingoism.

Because we can all see that’s the subtext here, right? To claim that English is the “most common language” when it is also the language (most) Americans speak is to appear to be making some of rah-rah ‘Murica statement. Except that… what happens if it’s just objectively true?

And it is objectively true. English has the greatest number of total speakers in the world by a wide margin. Even more tellingly, the number of English 2L speakers outnumbers Chinees 2L speakers by more than 5-to-1. This means that when someone chooses a language to study, they pick English 5 times more often than Chinese. No matter how you slice it, the fact that English is the most common language is just a fact about the reality we currently inhabit.

Not only that, but the connection of this fact to American chauvanism is historically ignorant. Not only is this a discussion about the English language and not the American one, but the linguistic prevalence of English predates the rise of America a great power. If you think millions of Indians conduct business in English because of America then you need to open a history book. The Brits started this stated of affairs back when the sun really did never set on their empire. We just inherited it.

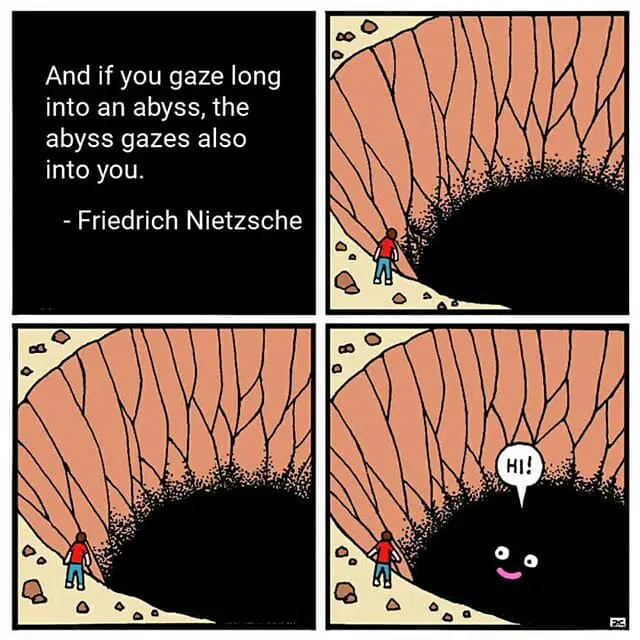

I wonder if there’s something about opposing something thoughtlessly that causes you to eventually, ultimately, become that thing. Maybe Nietzsche’s aphorism doesn’t just sound cool. Maybe there’s really something to it.

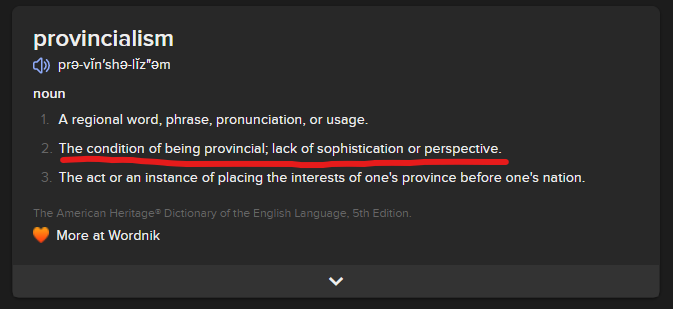

Part 2: Anti-Provincial Provincialism

My dad taught me the phrase “anti-provincial provincialism” when I was a kid. We were talking about the tendency of some Latter-day Saint academics to over-correct for the provincialism of their less-educated Latter-day Saint community and in the process recreate a variety of the provincialism they were running away from. Let me fill this in a bit.

First, a lot of Latter-day Saints can be provincial.

This shouldn’t shock anyone. Latter-day Saint culture is tight-knit and uniform. For teenagers when I was growing up, you had:

- Three hours of Church on Sunday

- About an hour of early-morning seminary in the church building before school Monday – Friday

- Some kind of 1-2 hour youth activity in the church building on Wednesday evenings

This is plenty of time to tightly assimilate and indoctrinate the rising generation, and for the most part this is a good thing. I am a strong believer in liberalism, which sort of secularizes the public square to accommodate different religious traditions. This secularization isn’t anti-religious, it is what enables those religions to thrive by carving out their own spaces to flourish. State religions have a lot of power, but this makes them corrupt and anemic in terms of real devotion. Pluralism is good for all traditions.

But a consequences of the tight-knit culture is that Latter-day Saints can grow up unable to clearly differentiate between general cultural touchstones (Latter-day Saints love Disney and The Princess Bride, but so do lots of people) and unique cultural touchstones (like Saturday’s Warrior and Johnny Lingo).

We have all kinds of arcane knowledge that nobody outside our culture knows or cares about, especially around serving two-year missions. Latter-day Saints know what the MTC is (even if they mishear it as “empty sea” when they’re little, like I did) and can recount their parents’ and relatives’ favorite mission stories. They also employ some theological terms in ways that non-LDS (even non-LDS Christians) would find strange.

And the thing is: if nobody tells you, then you never learn which things are things everyone knows and which things are part of your strange little religious community alone. Once, when I was in elementary school, I called my friend on the phone and his mom picked up. I addressed her as “Sister Apple” because Apple was their last name and because at that point in my life the only adults I talked to were family, teachers, or in my church. Since she wasn’t family or a teacher, I defaulted to addressing her as I was taught to address the adults in my church.

As I remember it today, her reaction was quite frosty. Maybe she thought I was in a cult. Maybe I’d accidentally raised the specter of the extremely dark history of Christians imposing their faith on Jews (my friend’s family was Jewish). Maybe I am misremembering. All I know for sure is I felt deeply awkward, apologized profusely, tried to explain, and then never made that mistake ever again. Not with her, not with anyone else.

I had these kinds of experiences–experiences that taught me to see clearly the boundaries between Mormon culture and other cultures–not only because I grew up in Virginia but also because (for various reasons) I didn’t get along very well with my LDS peer group for most of my teen years. I had very few close LDS friends from the time that I was about 12 until I was in my 30s. Lots of LDS folks, even those who grew up outside of Utah, didn’t have them. Or had fewer.

So the dynamic you can run into is when a Latter-day Saint without this kind of awareness trips over some of the (to them) invisible boundaries between Mormon culture and the surrounding culture. If they do this in front of another Latter-day Saint who does know, then the one who’s in the know has a tendency to cringe.

This is where you get provincialism (the Latter-day Saint who doesn’t know any better) and anti-provincial provincialism (the Latter-day Saint who is too invested in knowing better). After all, why should one Latter-day Saint feel so threatened by a social faux pax of another Latter-day Saint unless they are really invested in that group identity?

My dad was frustrated, at the time, with Latter-day Saint intellectuals who liked to discount their own culture and faith. They were too eager to write off Mormon art or culture or research that was amenable to faithful LDS views. They thought they were being anti-provincial. They thought they were acting like the people around them, outgrowing their culture. But the fact is that their fear of being seen as or identified with Mormonism made them just as obsessed with Mormonism as the mots provincial Mormon around. And twice as annoying.

Part 3: Beyond Anti

Although I should have known better, given what my parents taught me growing up, I became one of those anti-provincial provincials for a while. I had a chip on my shoulder about so-called “Utah Mormons”. I felt that the Latter-day Saints in Utah looked down on us out in the “mission field,” so I turned the perceived slight into a badge of honor. Yeah maybe this was the mission field, and if so that meant we out here doing the work were better than Utah Mormons. We had more challenges to overcome, couldn’t be lazy about our faith, etc.

And so, like an anti-Americanist who becomes an Americanist I became an anti-provincial provincialist. I carried that chip on my shoulder into my own mission where, finally meeting a lot of Utah Mormons on neutral territory, I got over myself. Some of them were great. Some of them were annoying. They were just folk. There are pros and cons to living in a religious majority or a minority. I still prefer living where I’m in the minority, but I’m no longer smug about it. It’s just a personal preference. There are tradeoffs.

One of the three or four ideas that’s had the most lasting impact on my life is the idea that there are fundamentally only two human motivations. Love, attraction, or desire on the one hand. Fear, avoidance, or aversion on the other.

Why is it that fighting with monsters turns you into a monster? I suspect the lesson is that how and why you fight your battles is an important as what battles you choose to fight. I wrote a Twitter thread about this on Saturday, contrasting tribal reasons for adhering to a religion and genuine conversion. The thread starts here, but here’s the relevant Tweet:

If you’re concerned about American jingoism: OK. That’s a valid concern. But there are two ways you can stand against it. In fear of the thing. Or out of love for something else. Choose carefully. Because if you’re motivated by fear, then you will–in the end–become the thing your fear motivates you to fight against. You will try to fight fire with fire, and then you will become the fire.

If you’re concerned about Mormon provincialism: OK. There are valid concerns. Being able to see outside your culture and build bridges with other cultures is a good thing. But, here again, you have to ask if you’re more afraid of provincialism or more in love with building bridges. Because if you’re afraid of provincialism, well… that’s how you get anti-provincial provincialism. And no bridges, by the way.

I might rewrite my pinned Tweet one day.