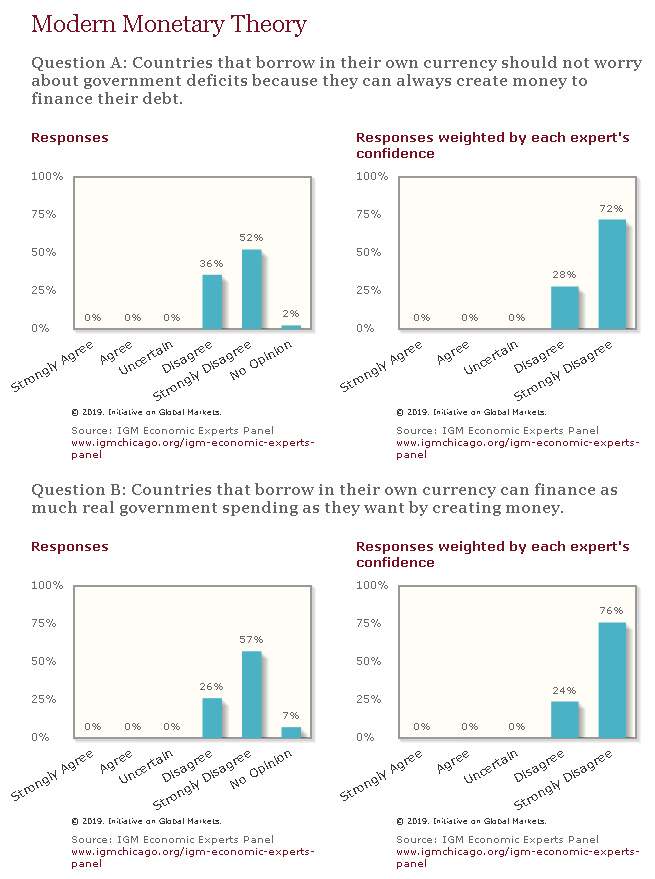

A new survey by the University of Chicago Booth School of Business finds that America’s top economists are not fans of Modern Monetary Theory:

So maybe it shouldn’t be a larger part of the public conversation.

I had another dream, I had another life

A new survey by the University of Chicago Booth School of Business finds that America’s top economists are not fans of Modern Monetary Theory:

So maybe it shouldn’t be a larger part of the public conversation.

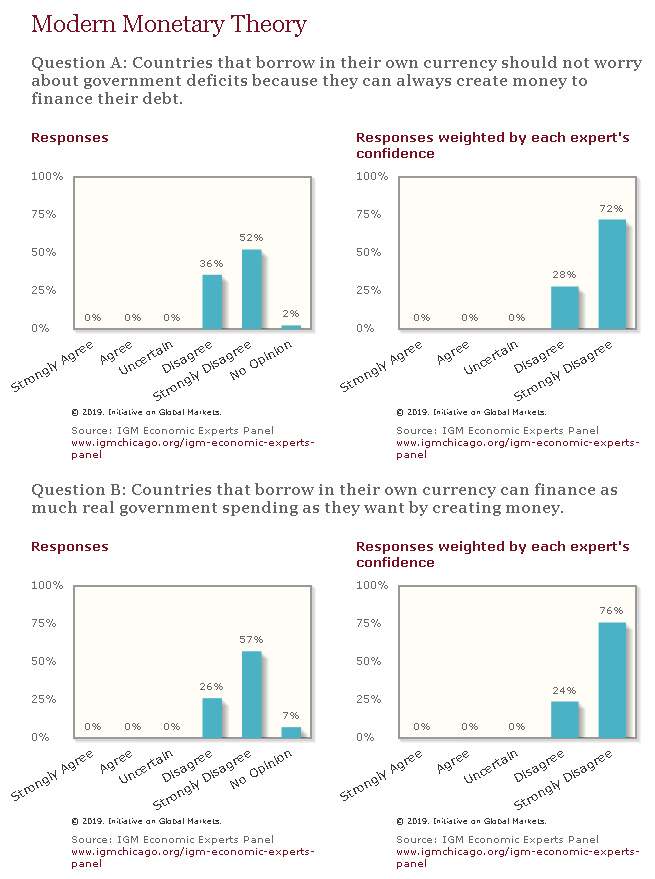

From a recent IMF working paper:

We use impulse response functions from local projections on a panel of annual data spanning 151 countries over 1963-2014. The main analysis on aggregate data is complemented with industry-level data.

Our results suggest that tariff increases have an adverse impact on output and productivity; these effects are economically and statistically significant. They are magnified when tariffs are used during expansions, for advanced economies, and when tariffs go up. We also find that tariff increases lead to more unemployment and higher inequality, further adding to the deadweight losses of tariffs. Tariffs have only small effects on the trade balance though, in part because they induce offsetting exchange rate appreciations. Finally, protectionism also leads to a decline in consumption; this, together with our findings, suggests that tariffs are bad for welfare.

All this seems eminently sensible and bolsters the arguments that mainstream economists make against tariffs; our results can be regarded as strong empirical evidence for the benefits of liberal trade. And given the current global context, we take special note of the negative consequences when advanced economies increase tariffs during cyclical upturns (pg. 25-26).

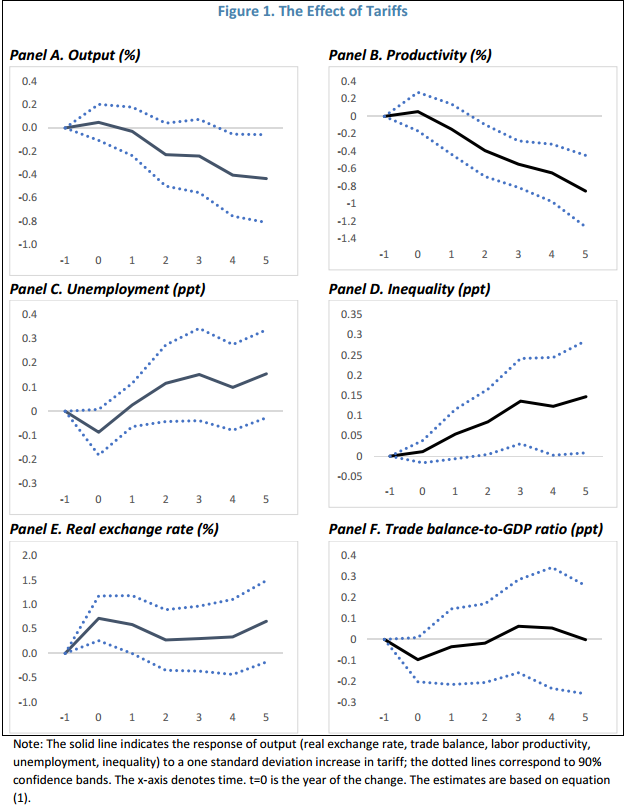

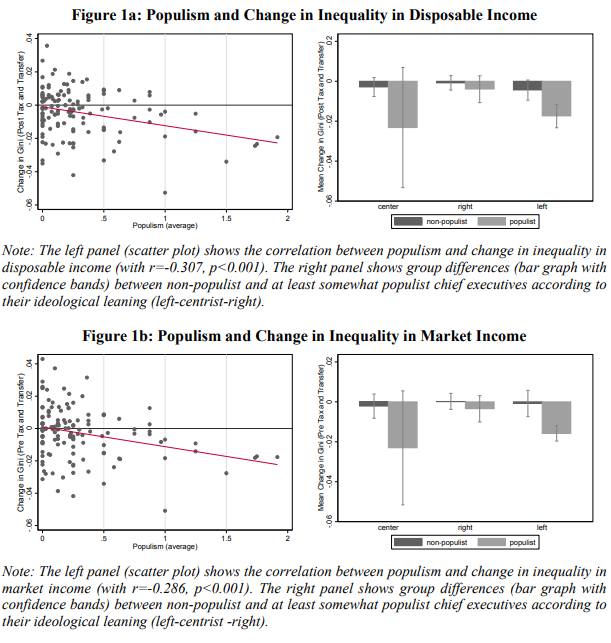

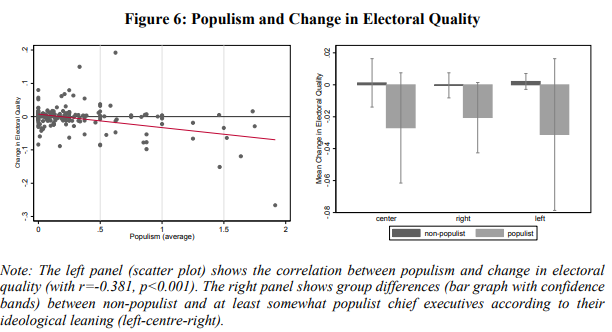

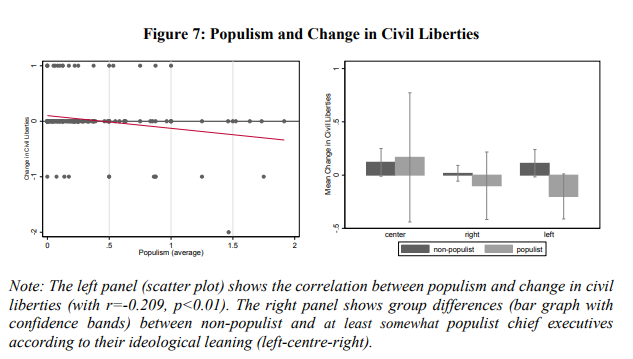

The above comes from a recent study of The New Populism project. This reduction in economic inequality may lead some populist supporters to feel vindicated. However, the study continues by pointing out that “the fiscal policies of populists are less progressive than non-populists. This is what we might have expected; they are not reducing inequality as a result of government taxation or welfare structures.” The mechanism remains unknown, “maybe minimum wage policies, maybe moves towards formalization of the labour force, or limits on income generation of the very wealthy (or even possibly in the case of Venezuela, the very wealthy leaving, thereby reducing overall levels of market inequality). But they do reduce overall levels of market inequality” (pg. 5).

However, this isn’t the only effect of populists:

So giving power over to populist authoritarians who undermine democratic institutions and civil liberties is one successful avenue to economic equality. The others, according to historian Walter Scheidel, are “mass-mobilization warfare, violent and transformative revolutions, state collapse, and catastrophic epidemics. Hundreds of millions perished in their wake, and by the time these crises had passed, the gap between rich and poor had shrunk.”

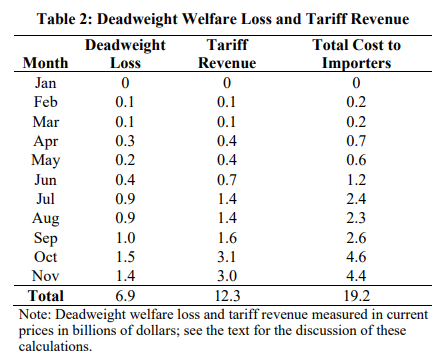

A new working paper confirms what economists have been saying about tariffs all along:

Economists have long argued that there are real income losses from import protection. Using the evidence to date from the 2018 trade war, we find empirical support for these arguments. We estimate the cumulative deadweight welfare cost (reduction in real income) from the U.S. tariffs to be around $6.9 billion during the first 11 months of 2018, with an additional cost of $12.3 billion to domestic consumers and importers in the form of tariff revenue transferred to the government. The deadweight welfare costs alone reached $1.4 billion per month by November of 2018. The trade war also caused dramatic adjustments in international supply chains, as approximately $165 billion dollars of trade ($136 billion of imports and $29 billion of exports) is lost or redirected in order to avoid the tariffs. We find that the U.S. tariffs were almost completely passed through into U.S. domestic prices, so that the entire incidence of the tariffs fell on domestic consumers and importers up to now, with no impact so far on the prices received by foreign exporters. We also find that U.S. producers responded to reduced import competition by raising their prices.

Our estimates, while concerning, omit other potentially large costs such as policy uncertainty as emphasized by Handley and Limão (2017) and Pierce and Schott (2016). While these effects of greater trade policy uncertainty are beyond the scope of this study, they are likely to be considerable, and may be reflected in the substantial falls in U.S. and Chinese equity markets around the time of some of the most important trade policy announcements (pg. 22-23).

So you’ve probably seen this article making the rounds: Google Finds It’s Underpaying Many Men as It Addresses Wage Equity. It’s not hard to see why. The idea that a socially-aware megacorp tried to equalize women’s pay and ended up handing out raises is not only intrinsically funny, but offers a dose of schadenfreude for all the folks who still think James Damore was fundamentally right about the tech giants ideological echo chamber. Fair enough. But I want to talk about something different, and the real reason I’m deeply skeptical of the whole idea of a gender pay gap.

The first thing to realize is that the entire concept of a pay gap is actually philosophically tricky to define. From the NYT article:

When Google conducted a study recently to determine whether the company was underpaying women and members of minority groups, it found, to the surprise of just about everyone, that men were paid less money than women for doing similar work.

OK, but how does Google define “similar work”? Probably–I’m guessing, but a guess is good enough in this case–by looking at stuff like job title. Do you think everyone who works at your company with the same job title as you is working as hard / getting as much done as you do? No? Then this isn’t a very good basis for assessing “similar work” is it?

In fact, the problem is really bad because–even if a company paid men and women equally given that they had the same job title (in this case Google appears to have paid women more) they could still discriminate at an earlier stage in the process. Thus (another quote from the NYT article):

Critics said the results of the pay study could give a false impression. Company officials acknowledged that it did not address whether women were hired at a lower pay grade than men with similar qualifications.

In other words, maybe Google pays senior developers the same (or even pays female senior developers more), but at the same time it also stacks the deck against new hires so that female applicants are more likely to get hired as regular developers and then men are more likely to get hired as senior developers. In that case, it could be true that Google is biased towards paying women more within one job title, but also that it’s biased towards paying women less overall.

Not so simple, eh?

Now, I don’t actually know if Google used job title to define “similar work” and I made the bold claim that I didn’t really care if they did or not. The reason for that is that there is no good way to measure how much work a person does. If they used job title, then that’s a bad proxy. But if they used something else, then I am confident that they used another bad proxy. Because there’s absolutely no practical way that Google could have spent the time and resources required to actually assess all of their workers. There’s a name for this in economics, for the ides that it’s basically impossible to measure how much work an employee is doing. It’s called the principle-agent problem. And, believe it or not, that’s actually the easy part. Even if you could accurately, easily, and cheaply quantify how much work your employees do (you can’t), there’s still no accepted methodology for assessing how much value that work contributed to the company. If you’re the sales guy who closes a deal that earns your company $1,000,000 in revenue you might think the answer is simple: your effort just got the company a cool million. But you didn’t do that alone. You were selling a product that you didn’t make, for one thing. So the designers, the marketing guys, and the folks on the assembly line building the widgets all need a cut. How do you attribute the value you made–$1,000,000–among all the complex, networked, interconnected contributors? Good luck with that.

So far, all I’ve really said is that trying to detect a wage gap is going to be really, really hard because assessing “similar work” is basically impossible. But there’s good news! If you understand the way markets work, you will understand that you have very, very good reason to be skeptical that men and women are really being paid different amounts for similar work.

Now, before I explain this, let me just point out that there are a lot of people who will tell you that economic models of markets are over-simplified, flawed, and misleading. They’re right, but those criticisms don’t really apply. There’s this whole controversial literature over concepts like the efficient market hypothesis that, luckily, we don’t need to get into here and now. In a nutshell, economists like to pretend (for the sake of tractable theories) that humans are perfectly rational and statistical geniuses who take all possible information into account when making purchasing decisions. If that were true, then things like market bubbles would (probably) not be possible. (It depends on the specific of your model.) So let me just say: yeah, I concede all that. Precise, mathematical models of markets are basically all wrong. We can quibble about whether they are “perpetual motion machine”-wrong or just “spherical chicken”-wrong, but whatever.

Here’s the point: in a market (even a fairly messed-up, realistic one) you’ve got a lot of companies who are all competing. Although there’s a lot going on, one vital way that one of these companies can get a leg up over its competitors is if it finds a way to offer the same good or the same service for less cost. This isn’t rocket science, this is really, really obvious. If company A and company B are both selling more or less interchangeable widgets, but company A can make them for $1.00 / each and company B can make them for $0.90 / each, then company B has a huge advantage.

So here’s the thing: if there were any real indication that you could hire a woman, pay her 70% of what you pay a man, and get “similar work”, then what you’re saying is that there’s an easy, obvious way to go out there and make your widgets for $0.70 when everyone else has to pay $1.00 to make theirs.

We don’t need to take any derivatives here. We don’t need advanced theory. We don’t need to assume that human beings are perfectly rational, hyper-calculating machines. We just have to assume that companies generally want to find ways to reduce the cost of the goods and/or services they sell. If that humble, uncontroversial assumption is true, then any perceptible evidence of a real gender pay gap would immediately be identified and exploited by the market.

If anyone could find a real gender pay gap, it would be the mother of all arbitrage opportunities. And look, folks, if there’s one thing that every red-blooded capitalist wants to find, it’s an arbitrage opportunity. This isn’t hypothetical, by the way. You look at an industry like currency trading, and companies invest huge amounts of money hiring geniuses, buying them super-computers, and paying for access to network cables that give them millisecond advantages so that they can find and identify arbitrage opportunities before the market erases them.

Because that’s what markets do. They look for chances to make free money and then they exploit them until they disappear. If you find out that you can trade your dollars for yen, your yen for rubels, your rubels for pesos, and then your pesos back to dollars and end up with more than you started with: that’s arbitrage. And you will immediately pump as much money as you can into running through that cycle. As a result, the prices will go up and the arbitrage opportunity will close. This is what markets do.

And so if there is a way out there to hire women to do men’s work for 70% (or whatever) of their pay, companies would do that instantly. And the result? Well, the first company would offer women $0.70 on the dollar, but then a competitor would offer them $0.71, and then another competitor would offer them $0.72… and pretty soon no more arbitrage.

So what’s my point?

Trying to find out if there actually is an real wage-gap is very, very hard because measuring “similar work” is difficult. But, if there is ever a whiff of a reliable, objective, solid gender pay gap it will disappear as quickly as it is spotted as the market rushes to exploit the arbitrage opportunity.

Here’s what it all comes down to: if you believe in the gender pay gap, you believe that a bunch of cold-blooded, selfish capitalists are staring at a pile of money left on the table, and not one of them is trying to get their hands on it. This isn’t a completely open-and-shut case, but it’s a very, very strongly suggestive argument that capitalism and wage inequality–of any kind: gender-based, race-based, sexual orientation-based, etc–are fundamentally incompatible in the long run. It doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t have laws against discrimination, because individual business owners might make stupid, bigoted decisions and we might decide not to wait around to let the market fix them. But it does mean that the idea of a real, persistent, ongoing gender pay-gap is like UFOs or Bigfoot or–even rarer than anything else–a free lunch.

It’s just probably not there.

A friend of mine posted an article on Facebook about a fun commuting game: patriarchy chicken. The idea is that you (a woman, of course) go about your commute as you ordinarily would do with one exception: you stop giving way to men. Because, you see,

Men have been socialised, for their entire lives, to take up space. Men who would never express these thoughts out loud have nevertheless been brought up to believe that their right to occupy space takes precedent over anyone else’s right to be there. They spread their legs on tubes and trains, they bellow across coffee shops and guffaw in pubs, and they never, ever give way.

New Statesman

The more I thought about this claim, the less sense it made. The article is written from the perspective of a Londoner, and so right away you have to ask: what’s the extent of this space-hogging socialization? Is it everywhere? Just the West? Just the Anglosphere? I mean, if this is really a think, then let’s take this seriously, right? Where are the cross-national studies? (Really, if you have any, send them my way.) It’s just odd that these new terms–mansplaining, manspsreading, etc.–crop out and then become part of the accepted wisdom with basically no analysis at all. Poof! They’re part of our (socially-constructed) reality.

Here’s the thing, though, I was certainly not socialized “to take up space”. As a man (that gives me some insight into how men are socialized, right?), my socialization included at least a couple of points contrary to the “take up space” model.

That’s how I was socialized. It’s not that I’m just ignorant of the “take up space” socialization, I was raised–in many ways–in the opposite school. And look, I’m not alone here. Most of the men I call friends act the same way. We don’t have to talk about it. We know. Because we apply the rules not only to ourselves individually, but also to ourselves in a group. If one man can be intimidating on accident, a group of two or three men have to be even more careful to avoid making anyone else uncomfortable.

Again, we don’t talk about it. It’s just a basic social rule that all guys know. Like the rule that you never, ever use a urinal adjacent to someone who’s already peeing if there are other free spots available. Never in my life growing up was I told that. It’s just basic man-code. So is giving way to women. Interested in more stuff like this? Check out the Art of Manliness website.

Alright, so if I–and a lot of men like me–have been socialized not to get in a woman’s way or expect her to move for us, then what gives? Is Charlotte Riley (who wrote the New Statesman article) lying? Hallucinating? No, I’m sure she’s not.

Here’s the thing, if every man out there expected women to get out of their way, then patriarchy chicken wouldn’t have sporadic run-ins, it would have a never-ending chain reaction of collisions. All it really takes is a small percentage–say, 5% off the top of my head–of men who expect women to get out of their way to be really, really noticeable. And here’s the thing, such men exist. We call them jerks. (If we’re being polite.) And they probably don’t see themselves as men who expect women to defer to them spatially. They see themselves as important people who expect everyone else to get out of their way.

In my experience, there are basically zero social justice concerns that can’t be reformulated without the political lens and be just as valid. This is just another example of that. Instead of unsubstantiated conspiracy theories about male socialization that strain credulity, why not go with the simpler approach: some people are jerks?

And, hey, look: if you want to play “jerk chicken” (which sounds delicious) instead of patriarchy chicken, great! Go for it. I’m not telling Riley–or anyone else–to do anything any differently. You be you. I just think it’s kind of sad that, left to their own devices, people seem so eager to adopt what are basically the social science version of conspiracy theories. It’s like choosing to live your life in as dark and depressing a light as possible. Yeah, you can go around thinking that all (most?) men secretly hate you and want to oppress you… but, in the absence of really strong data, why would you want to? It just seems sad.

That’s how most conspiracies work, though. They are fundamentally un-empowering. Nobody is empowered by the idea that aliens can swoop down in a UFO whenever they want, kidnap them, probe them, and then release them to a world that treats the story with derision. That’s not empowering! Nobody is empowered by the idea that we’re all just pawns of mysterious forces like the Illuminati. Conspiracy theories are basically an exercise in cashing in real control (agency over your actions and attitude and believes) for fake control (made-up explanations that remove the uncertainty and ambiguity of life). This trade-off doesn’t make a lot of sense when you put it on those terms, but that’s really what’s going on with conspiracy theories. People would rather be impotent in a world that makes sense than potent in a world that doesn’t.

The whole “Men have been socialised, for their entire lives, to take up space.” thing is not exactly the same, but it’s pretty close. Which makes it understandable, but still sad.

This is part of the Stuff I Say at School series.

The Assignment

Alexis de Tocqueville argues that the active involvement of American citizens in civil society distinguishes America from Europe and helps to prevent American government from becoming over centralized. In fact, civil society not only prevents Big Government from taking over, but enlarges each citizen’s life, helping them overcome the natural tendency of democratic citizens to isolate from each other. Contemporary social observers, like Robert Putnam and Marc Dunkelman, have seen trends of disengagement from civil society in their recent studies (and more engagement in virtual communities via technology). Discuss the significance of civil society from Tocqueville’s perspective and whether these recent trends of disengagement should be viewed as a cause of some alarm.

The Stuff I Said

Tocqueville’s view of civil society is very organic; a kind of pre-state network guided by cultural norms and both individual and communal pursuits. The bottom-up, arguably emergent nature of Tocqueville’s perception is likely why many classical liberal writers quote him so favorably. The ability of private individuals to organize to advance societal goals rather than relying on the coercion of the state appears to be deeply encouraged by Tocqueville. This makes public engagement a necessity to avoid “despotism.” This makes the decline in social capital potentially problematic.

However, there are a few points worth noting about the claims of social capital decline and the march toward despotism:

First and foremost, government has grown significantly since the mid 1800s. Democracy in America was written 20-30 years prior to the outbreak of the Civil War. My own state of Texas had not even been annexed yet. For all we know, Tocqueville might think we’ve been in the era of Big Government for over a century.

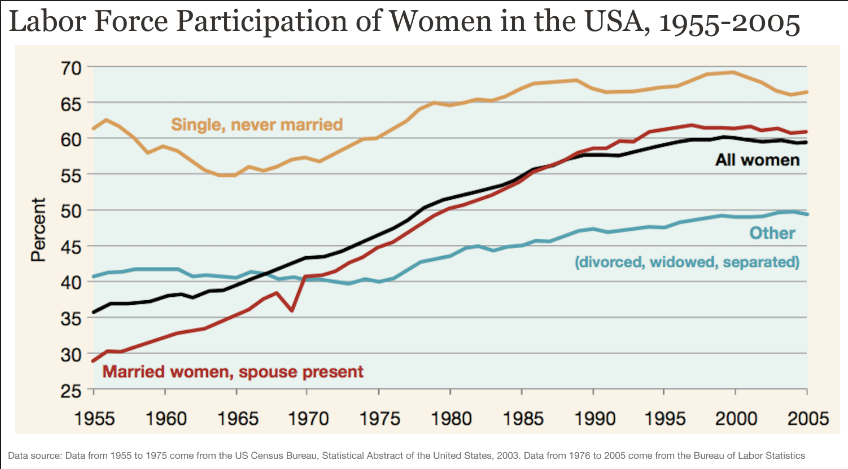

Next, economists Dora Costa and Matthew Kahn find that declines in social capital (i.e., volunteering and organization membership, entertainment of friends and relatives at home) between 1952 and 1998 were largely among women due to their increased participation in the labor force. Other contributors were income inequality and increasing ethnic heterogeneity. While income inequality can be a problem (it tends to erode trust), increasing diversity and female labor participation are, in my view, not negative developments.

Parents also appear to be spending more time with their children. For example, a 2016 study of 11 Western countries found that “the mean time the average mother in the 11 countries spent daily on child care in 1965 was calculated to be about 54 minutes, it increased to a predicted 104 minutes by 2012. For fathers, the estimates increased from a scant 16 minutes daily in 1965 to 59 minutes in 2012” (pg. 1090). Engaged parenting results in better child outcomes. So while parents may not be entertaining friends or bowling with buddies as much, they are giving their kids more attention. Considering Tocqueville’s focus on family, I think he would find this a plus (especially in the midst of the family fragmentation that has occurred over the last few decades).

But even with these declines, a majority of Americans still participate in various organizations. Drawing on the 2007 Baylor National Religious Survey, sociologist Rodney Stark finds that while 41% of Americans have no membership in non-church organizations, 48% had 1-3 memberships and 11% had 4-5 memberships. “About six Americans out of ten belong to at least one voluntary organization. Add in church organizations and the number rises to more than seven out of ten, and the median becomes two memberships” (pg. 122-123).

Finally, the labor market was dominated by agriculture (76.2% in 1800; 53.6% in 1850) during the period that Tocqueville wrote. By the turn of the 20th century, however, most of the labor force could be found in manufacturing (35.8%) and service sectors (23.6%). By the 21st century, service had come to dominate the labor market (73% in 1999). While social capital in the form of organizational participation may have declined over the last half century, the kind of work we do has changed drastically. This includes our workplace experience. We actually have co-workers that we spend hours each day cooperating with and customers that we are obligated to respect day in and day out. The relationships (and social capital) we establish through the workplace are very different from 19th-century farms or even industrial-era factories. The late Peter Drucker believed that today’s business institutions “are increasingly the means through which individual human beings find their livelihood, find their access to social status, to community and to individual achievement and satisfaction” (pg. 16). I don’t think we should underestimate the long-run impact of commerce on social capital. Numerous studies find that markets foster socially-desirable traits like trust, cooperation, and tolerance.[ref]Another classmate pointed out that it’s likely too soon to tell whether or not internet-based communities can fulfill the same civic functions as older forms. I think his point about the internet is really important. The concern over “echo chambers” may in fact be far overblown. Granted, there is evidence that suggests social media does increase things like political polarization. But we may really be underselling the benefits of greater connectivity via technology (especially through social media and mobile phones).[/ref]

In short, I think Tocqueville might find some of our over-reliance on government distasteful, but overall would be impressed with how incredibly adaptive the American people have been over the course of nearly two centuries of rapid change and development. This latter point would confirm many of the observations he made about the underlying mores of American civil society.

This is part of the Stuff I Say at School series

The Assignment

Although scholars generally agree on the timing of of the first few critical elections/realignments, consensus breaks down on the timing of the 6th and 7th party systems. Do you think the 6th party system began in 1968, 1980, or sometime later? What about the 7th party system? Please think critically and resist giving the answer you hope to be true.

The Stuff I Said

Political psychologist Lilliana Mason argues that over the last 50 years or so, parties have become “more homogeneous in ideology, race, class, geography, and religion,” causing “partisans on both sides [to feel] increasingly connected to the groups that [divide] them” (pg. 40). In other words, political partisanship has become associated with other forms of social identity and therefore has itself become an identity. For example, “party identity is strongly predicted by racial identity, not racial-policy positions (Mangum 2013). The parties have grown so divided by race that simple racial identity, without policy content, is enough to predict party identity. The policy division that began the process of racial sorting is no longer necessary for Democrats and Republicans to be divided by race. Their partisan identities have become firmly aligned with their racial identities, and decoupled from their racial-policy positions” (pg. 33, italics mine). It is this fusion of social and political identity that leads me to lean in favor of those scholars that identify the 1980s with the emergence of the 6th party system. I lean this way largely due to the rise of the Religious Right in the 1970s (I’d add the rise of “neoliberal” ideology associated with Reagan and Thatcher and solidified by the fall of the Berlin Wall, the collapse of the Soviet Union, and the ending of the Cold War). While Jimmy Carter was popular among religious conservatives, many of his policy stances alienated these same voters, paving the way for Reagan and the Republican identification with conservative Christians. By 1992, the religious divide between Democrats and Republicans had, in Mason’s words, “cracked open…The difference between the parties on the percentage of weekly churchgoers had increased to an 11 percentage point gap, with Republicans more churchgoing than Democrats. Connected to this new divide, Democrats in 1992 were only 2 percent more Catholic than Republicans. Twenty years earlier the difference had been 13 percentage points. The conservative religious were moving toward the Republican Party” (pg. 36). By 2012, “parties differed by 14 percentage points in how many attend religious services each week” (pg. 37).

I’m unsure if a firm 7th political system has arisen. However, I think we’re beginning to see the crumbling of the 6th party system. The identity politics mentioned above will likely increase in the era of globalization and social media. The election of Trump may be the first inklings of an identity politics party system, along with the recent uptick in student activism and fragility on college campuses. What’s worse, having more extreme political views actually increases one’s happiness. From a recent study:

Results show that congruence of political affiliations of national politicians, especially the president, with individual party affiliation has an effect on reported happiness while there is no effect of state, gubernatorial or legislative, party congruence. Individuals report being happier when the president is a member of their own party. Throughout all specifications, republicans and those holding conservative political values report higher happiness. Shockingly, regardless of liberal or conservative political values, those who hold extreme political values report higher levels of happiness. The large effect of partisanship and extreme views on reported happiness support the view that partisanship is a result of social identity and provides a psychological need for certainty and structure (pg. 10).

Economist Arthur Brooks, current president of the American Enterprise Institute, made this point years ago in his book Gross National Happiness:

Americans who describe themselves as holding extreme political views–somewhere between 10 and 20 percent of the population–are among the happiest people in America. All of those angry protesters who denounce Dick Cheney as a murderer; all of the professional political pundits who use the rhetoric of rage and misery to get on cable television–it turns out they’re not miserable at all. On the contrary, they’re enjoying themselves rather a lot.

In 2004, 35 percent of people who said they were extremely liberal were very happy (versus 22 percent of people who were just liberal). At the same time, a whopping 48 percent of people who were extremely conservative gave this response (compared with 43 percent of nonextreme conservatives). Indeed, the gusto with which Bill Clinton’s attackers in 1998 went after him was really a clue that they were having a grand old time. George W. Bush’s harshest critics–those who have felt the predations of the Bush administration to the very depths of their soul–are quite likely to be a great deal happier than more moderate liberals.

Why are ideologues so happy? The most plausible reason is religion–not real religion, but rather, a secular substitute in which they believe with perfect certainty in the correctness of their political dogmas. People want to hold the truth; questioning is uncomfortable. It is easy to live by the creed that our nation’s ills are because of George W. Bush; it is much harder to acknowledge that no administration is perfect–or perfectly awful. True political believers are martyrs after a fashion willing to shout slogans in public for causes they are sure are good, or against causes they are convinced are evil. They are happy because–unlike you, probably–they are positive they are right. No data could change their minds (pgs. 33-34).

In other words, being a political hooligan feels really good, which makes change unlikely once you’ve discovered the One True Party. Unfortunately, as Brooks points out,

the happiness of political extremists is an unhappy fact for America. They may themselves be happy, but they make others unhappy–that is, they actually lower our gross national happiness. In many cases, extremists actually intend to upset people–it is part of their strategy…Extremists are happy to stir up their own ranks, but they are even happier when they cause misery for their political opponents. For people on the far left and right, people who do not share their views are not just mistaken, but bad people, who are also stupid and selfish. They deserve to be unhappy…Extremists thrive on dehumanizing their opponents (pgs. 34-35).

This is an impressive statement. It features 3333 economists, 4 former chairs of the Federal Reserve, 27 Nobel laureates, 15 former chairs of the Council of Economic Advisers, and 2 former Secretaries of the U.S. Treasury Department.

Their recommendations:

I. A carbon tax offers the most cost-effective lever to reduce carbon emissions at the scale and speed that is necessary. By correcting a well-known market failure, a carbon tax will send a powerful price signal that harnesses the invisible hand of the marketplace to steer economic actors towards a low-carbon future.

II. A carbon tax should increase every year until emissions reductions goals are met and be revenue neutral to avoid debates over the size of government. A consistently rising carbon price will encourage technological innovation and large-scale infrastructure development. It will also accelerate the diffusion of carbon-efficient goods and services.

III. A sufficiently robust and gradually rising carbon tax will replace the need for various carbon regulations that are less efficient. Substituting a price signal for cumbersome regulations will promote economic growth and provide the regulatory certainty companies need for long- term investment in clean-energy alternatives.

IV. To prevent carbon leakage and to protect U.S. competitiveness, a border carbon adjustment system should be established. This system would enhance the competitiveness of American firms that are more energy-efficient than their global competitors. It would also create an incentive for other nations to adopt similar carbon pricing.

V. To maximize the fairness and political viability of a rising carbon tax, all the revenue should be returned directly to U.S. citizens through equal lump-sum rebates. The majority of American families, including the most vulnerable, will benefit financially by receiving more in “carbon dividends” than they pay in increased energy prices.

In January 2019, I started my MA program in Government at John Hopkins University. With homework taking up a more significant amount of my time, my blog-related research is certainly going to suffer. Instead of admitting defeat, I’ve decided to share excerpts from various assignments in this series. I was inspired by the Twitter feed “Sh*t My Dad Says.” While “Sh*t I Say at School” is a funnier title, I’ll go the less vulgar route and name it “Stuff I Say at School.” Some of this material will be familiar to DR readers, but presenting it in a new context will hopefully keep it fresh.

Below you’ll find links to all posts in the series.