I’ve got serious misgivings with the way “privilege” is often used in political discourse these days, where the assumption is always that it’s racial, gender, or other forms of privilege that matter most. It’s not in any way that I deny that these forms of privilege exist, but the discussion is too simplistic and too myopic. Privilege is not absolute. It’s contextual. And race and gender and sexuality and other identity-based forms of privilege aren’t the only forms that exist. They aren’t even the most important. More important? The privilege of coming from a stable, two-parent, biological family, for one, and the privilege of a low ACE-score for another.

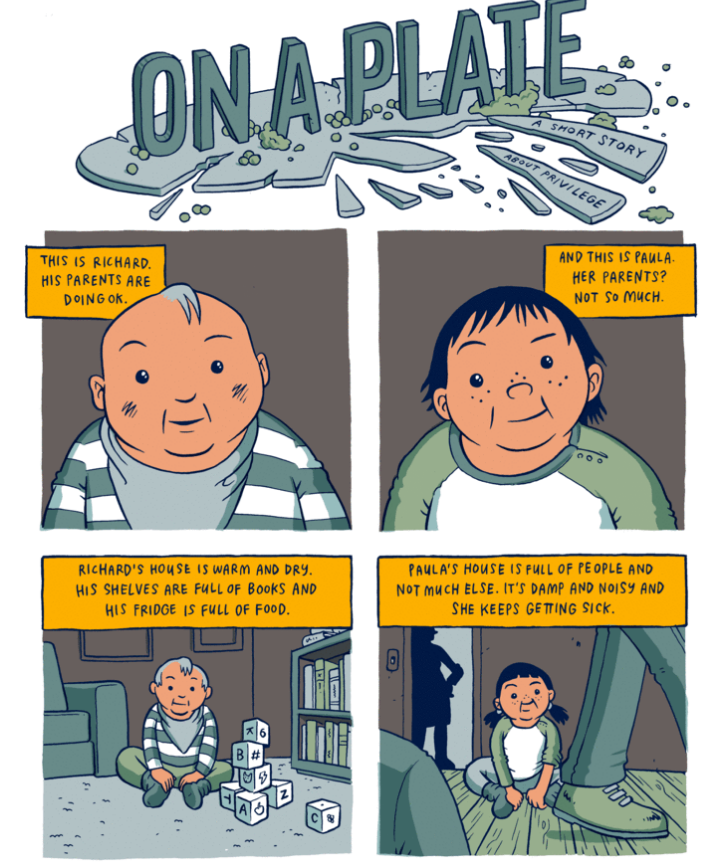

So, although most of the folks who share this comic (and possibly the author, too) would probably disagree vehemently with me over the topic, I share it because it’s actually a very, very good example of how privilege really works:

What’s really good about the comic is that it actually illustrates specific examples of privilege and, in this case, the privilege of class. The two children both have strong families, are both white, and gender doesn’t focus prominently in the storyline. Instead, it’s all about who can afford to study while in college vs. who has to shoehorn studies and menial work into the same schedule.[ref]Been there, done that.[/ref] It’s also about who has family connections that can smooth the transition into a competitive job environment, and who has to figure things out on their own.

Class is a better framework for discussing privilege than race or gender (although race-based and gender-based privilege do exist) because it gets closer to the heart of the matter: power. The trouble is that Americans don’t really like class. We’re not sure what it means and we kind of like to pretend it doesn’t exist. No one is more keen to pretend that class is not an issue then the upper-class, of course. This is one reason for the fascinating relationship of brand prominence to price.

Today, anyone can own a purse, a watch, or a pair of shoes, but specific brands of purses, watches, and shoes are a distinguishing feature for certain classes of consumers. A woman who sports a Gucci “new britt” hobo bag ($695) signals something much different about her social standing than a woman carrying a Coach “ali signature” hobo ($268). The brand, displayed prominently on both, says it all. Coach, known for introducing “accessible luxury” to the masses, does not compare in most people’s minds in price and prestige with Italian fashion house Gucci. But what inferences are made regarding a woman seen carrying a Bottega Veneta hobo bag ($2,450)? Bottega Veneta’s explicit “no logo” strategy (bags have the brand badge on the inside) makes the purse unrecognizable to the casual observer and identifiable only to those “in the know.”

One function of this kind of invisible prestige (although not the only consideration) is that it allows the most privileged to avoid attracting attention from those who are less privileged. Only their fellow elites can recognize their subtle status cues. This is also the reason that identity-based privilege is so appealing to middle- and upper-class Americans: it obscures more privilege than it reveals by quietly taking class off the table. Identity-based privilege is loud and boisterous, but it poses a negligible threat to existing socio-economic power structures. It’s about as revolutionary as a Che Guevara t-shirt.