Ender’s Game is, more than any thing else, a book about empathy. From the very first line of the book (“I’ve watched through his eyes, I’ve listened through his ears…”) and on to the end the theme of empathy dominates everything the characters do and think about. It is the key to all of young Ender’s victories and the source of his greatest strength. It is the source of his deepest pain.

Why, then, is the author of Ender’s Game an unrepentant homophobe and conspiracy theorist best described alternatively as either “intolerant” or “kooky”? That is the question Rany Jazayerli asks in his moving and thoughtful piece for Grantland. Jazayerli is clearly a sympathetic reader (sympathetic of Card, I mean). As a devout Muslim he shares Card’s Mormon view that homosexual sex is a sin. He is not only a fan of science fiction in general and Card’s works in particular, he writes movingly of how Card’s sympathetic depiction of a Muslim character in Ender’s Game (written in the 1980s) profoundly touched Jazayerli. He says:

Why, then, is the author of Ender’s Game an unrepentant homophobe and conspiracy theorist best described alternatively as either “intolerant” or “kooky”? That is the question Rany Jazayerli asks in his moving and thoughtful piece for Grantland. Jazayerli is clearly a sympathetic reader (sympathetic of Card, I mean). As a devout Muslim he shares Card’s Mormon view that homosexual sex is a sin. He is not only a fan of science fiction in general and Card’s works in particular, he writes movingly of how Card’s sympathetic depiction of a Muslim character in Ender’s Game (written in the 1980s) profoundly touched Jazayerli. He says:

Others may hate him, but I’m still struggling to understand him. That’s the least I owe him for gifting me with an ethical compass when I needed one.

I’d like to help Jazayerli understand Card.

Card’s View on Marriage

Jazayerli correctly pinpoints Speaker for the Dead as the spiritual center of Ender’s story. In Speaker for the Dead, Card explains his views on marriage. Written in the early 1980s, these views don’t address the gay marriage debate in any way. But if you’re going to critique Card’s views on gay marriage you have to start with an understanding of his views on marriage in general.

Jazayerli correctly pinpoints Speaker for the Dead as the spiritual center of Ender’s story. In Speaker for the Dead, Card explains his views on marriage. Written in the early 1980s, these views don’t address the gay marriage debate in any way. But if you’re going to critique Card’s views on gay marriage you have to start with an understanding of his views on marriage in general.

There are basically two beliefs to keep in mind. First, Card things that marriage is important. Really, really, really important. Second: Card believes that the institution of marriage is defined not by the relationship between the spouses (with each other), but rather by the relationship between the spouses (as one unit) and the larger community (as the other unit).

In the introduction to the definitive edition of Speaker for the Dead he addresses the book’s obsessive theme (just as important to it as empathy was to Ender’s Game) by writing that “few science fiction heroes seemed to marry and have kids. In short, the heroes of most science fiction novels were perpetual adolescents.” Card wants to talk about the transition from the freedom of adolescence to the burdens of adulthood, and this is how he describes the problem:

Only when the loneliness becomes unbearable do adolescents root themselves, or try to root themselves… And, in fact, many fail at adulthood and constantly reach backward for the freedom and passion of adolescence. But those who achieve it are the ones who create civilization… The most important stories are the ones that teach us how to be civilized: the stories about children and adults, about responsibility and dependency.

In Card’s view we all have a naturalistic inclination towards hedonistic selfishness. Those who follow this inclination, no matter their age, are adolescents. The alternative is to accept the shackles of responsibility and dependency and become adults, and it is those who successfully yoke themselves to the serious business of community who become the basis for civilization itself. The kernel and exemplar of this system is traditional, monogamous marriage. In that institution, the spouses give up their freedom and accept mutual obligation and fidelity to each other and thus create the stable foundation for creating and nurturing new life.

It might seem like cheating to quote so extensively from the introduction (not everyone reads introductions), but the themes are presented just as starkly in the text itself. For example:

Marriage is not a covenant between a man and a woman; even the beasts cleave together and produce their young. Marriage is a covenant between a man and woman on the one side and their community on the other. To marry according to the law of the community is to become a full citizen; to refuse marriage is to be a stranger, a child, an outlaw, a slave, or a traitor. The one constant in every society of humankind is that only those who obey the laws, tabus, and customs of marriage are truly adults.

That passage isn’t from the introduction. It’s from page 152 of the text itself. It highlights both points: heterosexual marriage is the foundation of society and marriage “is a covenant between a man and a woman on the one side and their community on the other.”

Marriage is so vitally important to Card that he creates a new Catholic order named “Children of the Mind of Christ” which includes married but celibate priests and nuns. In a world that increasingly believes marriage is an extraneous obstacle to pleasurable sex, Card creates an example of an institution that is totally vital, but to which sex itself is not essential. This doesn’t mean Card is anti-sex, but it illustrates how passionately devoted he was at least as far back as the 1980’s (well before gay marriage was a national debate) to the vital role of marriage as a binding social contract rather than as a comfortable and convenient living arrangement.

The Conflict with Gay Marriage

It is obvious from the identification of marriage and procreation that when Card talks about marriage he means heterosexual marriage, but the question becomes: why not include gay marriage? Is the institution of marriage as Card defines it in any way threatened by the existence of gay marriage? The answer to that is “no,” and I think even Card might agree with me on it given this caveat. Gay marriage itself does not threaten the institution of marriage, but the particular arguments being used to advance gay marriage right now do.

This might seem like splitting hairs. It is not. Nate Oman has explained this case clearly:

Much of the public discussion around gay marriage strikes me as deeply troubling. Gay marriage has emerged as a civil rights issue, for many as the central civil rights issue of this generation. Framing the issue in this way, however, strikes me as mistaken and potentially destructive. The language of civil rights focuses our attention on the ideas of equality, liberty, and legal rights. None of these strike me as very productive or complete ways of thinking about marriage. Marriage is about a hierarchy of family statuses, in which a certain form — marriage — is enshrined as preferable to others. Likewise, marriage is in an important sense about limiting freedom, both by raising the costs of exit and by providing a locus for creating and enforcing social norms that try to constrain behavior. My worry is that entrenching ideas of equality, liberty, and legal rights in our public understanding of marriage will tend to erode it’s social and cultural potency at the margins.

I don’t want anyone to come away thinking that I’m arguing that Nate Oman supports Orson Scott Card’s views. Obviously he does not. But he does demonstrate that a policy rationale can be as important as the policy itself. Therefore someone could support gay marriage and still criticize the gay marriage movement.

If the gay marriage movement was about replicating the institution of traditional marriage for homosexuals that would be one thing. That’s the hypothetical world where I could see Card plausibly supporting gay marriage, or at least fearing it a lot less. In the real world, however, that’s not what the movement does. Whereas traditional heterosexual marriage asks not what marriage can do for spouses, but what spouses must do for marriage (it is about “limiting freedom” as Oman says), modern heterosexual marriage increasingly shifts the emphasis from duty and responsibility to convenience and commodity. The biggest step in that direction was the ill-fated move towards no-fault divorce. It was supposed to make it easier for abused women to exit marriages (a noble goal). The assumption was that if divorces were easy to obtain, all unhappy marriages would dissolve and only happy marriages would remain. Despite skyrocketing divorce rates, this goal has failed miserably, and the institution of marriage was substantially weakened in our society. (The same logic was supposed to mean that elective abortion would mean the end of child abuse. If only wanted children were allowed to live, then all children would be wanted, and no one would abuse them. That hasn’t worked out either.)

The gay marriage movement will compound this erosion, but not primarily because of gay sex. Rather, it’s the doubling-down on the idea of marriage as a means to an end–as something that people do because of the benefits it provides–that will further warp the institution of marriage in our society.

The movement towards gay marriage doesn’t necessarily have to take this course. In theory, at least, gay marriage advocates could also be doubling down on the importance of monogamy and working to roll back no-fault divorce. In practice, that’s not happening. In practice, gay marriage is predicated on driving the stake deeper towards the heart of marriage. It treats the institution as instrumental rather than fundamental and questions whether monogamy even makes sense as part of the definition at all.

Gay marriage didn’t have to be the enemy of Card’s view of marriage in theory. In practice, it is. His two fundamental points where that 1) marriage is vitally important to society and 2) marriage is about what you give rather than what you get. He is opposed to gay marriage for the second reason, and he is passionate in his opposition for the first reason.

It’s all there in the text for anyone who cares to look.

Card’s Homophobia

I was floored when I came across Janis Ian’s passionate 2009 defense of her friend Orson Scott Card. Ian, an out lesbian, writes:

I was floored when I came across Janis Ian’s passionate 2009 defense of her friend Orson Scott Card. Ian, an out lesbian, writes:

Let me say first that I consider Scott a close friend; the time we don’t have together physically, we make up through the heart. If I had to lean on someone, or needed an ear, I would think of him. And if you’ve read my autobiography, you’ll know that in a time of great trouble, he was very, very, good to me. By the way, the gay community was nowhere to be seen when I was at my lowest.

She goes on:

And speaking of my partner… Scott has never treated my relationship, or my partner, with anything but the utmost respect. We’ve been welcomed into his home, invited to his childrens’ weddings, sent announcements of births and deaths – all to both of us, as a family unit. His children regard us as a family unit, and I’ve never heard or felt the slightest breath of censure from any one of them.

This is a direct contradiction of the idea that opposition to gay marriage is identical to personal hatred of homosexuals. It further strengthens the idea that Card’s opposition to gay marriage might be about something other than intolerant bigotry. But it does raise a perplexing question at first glance. If (according to the text of Speaker for the Dead) the only real marriage is heterosexual marriage those who don’t get married must be ” a stranger, a child, an outlaw, a slave, or a traitor”, then what’s going on? Which one does Card think that Ian is: stranger, child, outlaw, slave, or traitor?

There’s no question that, in Card’s view, homosexuals are outsiders. But he’s not alone in that belief. Dissident feminist Camille Paglia (also an out lesbian) recently participated in a debate at American University with the topic: “Gender Roles: Nature or Nurture.” Paglia took the position the gender essentialist position, that gender roles are largely biologically determined. In her opening statement she said that “Gender questioning has always been and will remain the prerogative of artists and shamans, gifted but alienated beings.” (Emphasis added.)

There’s no question that, in Card’s view, homosexuals are outsiders. But he’s not alone in that belief. Dissident feminist Camille Paglia (also an out lesbian) recently participated in a debate at American University with the topic: “Gender Roles: Nature or Nurture.” Paglia took the position the gender essentialist position, that gender roles are largely biologically determined. In her opening statement she said that “Gender questioning has always been and will remain the prerogative of artists and shamans, gifted but alienated beings.” (Emphasis added.)

Paglia and Card seem to agree on this essential characteristic of the LGBT community: they are outsiders. Paglia says that as one of the outsiders. Card, for his part, says that as someone who has spent his entire career writing with compassion about outsiders. Whether it’s the alien Formics, sympathetic Muslim or Jewish characters, or courageous homosexuals (see The Ships of Earth series), Card has always believed that outsiders can be loved and appreciated if we take the time to understand them. And that we should take the time to understand them. Combining that trait with Ian’s personal testimony, I believe it is reasonable to see that Card’s opposition to gay marriage does not stem from bigotry.

It is also worth noting that, in Ender’s Game, Card depicted the struggle between the humans and the outsider Formics as being essentially a misunderstanding. But he also seemed to at least partially justify the harsh tactics used by the humans (and also by Ender on a smaller scale) as a matter of self-preservation. The juxtaposition of empathy and conflict shouldn’t be surprising to anyone who has paid attention while reading Ender’s Game. It’s not that hard to see Card as simultaneously embracing the gay community as outsitders to be loved, and also engaging in what he sees as a battle for social survival against the gay rights movement. It is, after all, eerily similar to his depiction of Ender’s simultaneous love for and opposition against his own enemies.

This is Not What Tolerance Looks Like

The assumption that the only possible explanation for opposition to gay marriage must be bigotry is, itself, deeply troubling. The world has forgotten what tolerance really looks like. Tolerance doesn’t mean congeniality in the absence of genuine disagreement. Tolerance presupposes genuine and irreconcilable differences. Otherwise: what’s the point?

Jazayerli is unwilling to come out and state that he believe gay sex is sinful, but he comes fairly close when he writes that:

Most of the world’s major religions consider gay sex a sin, and anyone who thinks a religious person should get over that belief, or the belief in sin generally, fundamentally misunderstands what it means to be religious.

You just have to connect the dots (Jazayerli states the he’s a devout Muslim who abstains from alcohol) to conclude that he probably believes gay sex is a sin. He defuses this tension, however, by arguing for a dichotomy between sin and crime.

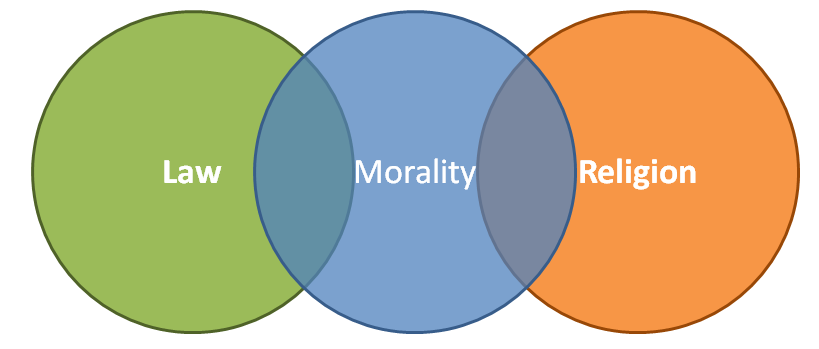

Superficially this makes sense. No one likes a theocracy. We all understand that an attempt to criminalize every immoral act would itself be immoral. But that’s the catch: the question of where to draw the line between public concern and private vice is itself a moral consideration. That is why Jazayerli’s superficial reference to the First Amendment doesn’t actually make any sense. He seems to be saying that law and religion are two totally separate and distinct spheres with no overlap. This is impossible: they are both inextricably interwoven with moral consideration and there’s no use pretending otherwise.

Jazayerli’s position is vapid. It’s not a principled argument that explains why Jazayerli believes some immoral acts (like theft) should be criminalized and other immoral acts (like drinking alcohol) should not be and still other immoral acts (like lying) should be criminalized some of the time but not other times. It is, in fact, just acquiescence to the popularity of the gay rights movement. Jazayerli is applying the basic tactic: if you can’t beat ’em, join ’em. And so he downplays the disagreement and pretends that this is tolerance. It’s not.

A fundamental tactic of the gay rights movement is to accuse anyone who disagrees with their policies of being bigoted. Which is exactly what Jazayerli seems to do with Card. Jazayerli is collaborating. He is demonstrating to the ascendant, socially liberal culture that he is willing to get with the program. It’s a foolish and short-sighted tactic. The time is quickly coming when even Jazeyerli’s subtle admission that he views gay sex as sinful will itself become sufficient grounds for the accusation of bigotry. (For plenty of people: it already is.) It’s only a matter of time until Jazayerli’s piece castigating Card for his bigotry could come to be used as evidence of the same claim against him.

Tolerance is not pretending that you don’t have a disagreement because you don’t want to get picked on or mocked. Tolerance is admitting that you do have a disagreement, but treating people with respect anyway. Card succeeds at tolerance in his fiction writing, but fails in his columns. So does Jazayerli, although at the other end of the spectrum. Card is overly adversarial and Jazayerli is disingenuously compliant.

A Limited Defense

I stand somewhere between Nate Oman (who favors gay marriage, but questions the gay rights rhetoric) and Orson Scott Card (who criticizes both). My defense of Card must therefore be a limited one. I think it’s plain from his writings and his relationship with his gay friends that Card is not a bigot.

But he does say some crazy things. Oh boy, are they crazy.

I really can’t deny that, and I can’t defend it either. I’m not really sure why I’d want to, however. He’s hardly the first famous and talented writer to have kooky beliefs. It’s practically part of the job description, as far as I can tell. The problem is that his artistic kookiness lines up with his politics at a time when those views are the subject of a heated national debate. Lots of authors seem to subscribe to weird politics (Robert Heinlein’s libertarian-fascist-free-love fusion, anybody?), but when they aren’t part of a larger public discourse no one pays them any mind.

Card’s comments on gay marriage–and position on the board of NOM–have put the rest of his political musings in the spotlight, however. And they don’t bear up well under scrutiny. His political theory about President Obama nominating Michelle Obama to run in 2016 and then using that as a stepping-stone to totalitarian domination or whatever is what Jazayerli says it is: a conspiracy theory. His language about gay marriage has also been incendiary and irresponsible.

I think to some extent Card has been acting out of frustration. Being accused of bigotry instead of having your arguments addressed can be infuriating. Add to that the insularity of long-held fame and a fear that your civilization is being cut to the bone and it’s not hard to see how fear and anger could lead to his outbursts.

This may be an explanation, at least in part, but it is not an excuse. The fatal flaw in the opposition to gay marriage has been from the very start an absence of love. I’m happy that many in the movement have learned this lesson and are working to build bridges, speak peacefully, and show love to their gay brothers and sisters, but it’s probably too late for a movement which was complicit for too long in allowing itself to be defined by hatred and fear. Card seems to be a one-man object lesson, and his language has been insensitive to an inexcusable degree.

In his political writings, anyway. In his fiction–which I prefer to read–he has laid his arguments out far more carefully and with much greater compassion and sensitivity. And that’s the last thing I have to say to Jazayerli, I suppose:

If you want to understand the man, read the works he has put his heart and soul into. I hope and believe that works like Ender’s Game and Speaker for the Dead will far outlast the memory of his rants and conspiracy theories. And I think they should, because I’d like to believe they are a clearer reflection of the man behind them.

But hey, even if they’re not, at least they are good enough on their own merits.

You missed the point on his ‘kooky theory’ about Michelle Obama in 2016, etc. That article was written to show more about writing and imagination that what he actually thought would happen. He specifically said he didn’t believe it would happen.

It’s not that simple.

First: there are plenty of conspiracy theories in that article. As a simple example: “When our consulate in Benghazi was under attack andwe had the means to stop it, he did absolutely nothing.” There has never been credible evidence that we had the means to stop the Benghazi attack. This is a conspiracy theory.

Second: the larger point of his post was that fiction is vital in predicting real-world changes. He gives an example earlier on to show that he’s being deadly serious:

That’s a real prediction of a real event, and it’s in that vein that he proceeds to make his prediction about an Obama power-grab. Note that, while he’s not asserting that his theory will happen, he is adamant that it is plausible.

Also:

And:

In addition to the repeated use of the word “plausible” and the reference to his own prediction of the downfall of the USSR, note that all of the historical analogues are just that: historical. He then gives his theory, and wraps it up this way:

Note how he goes immediately from “this won’t happen” to “anything can happen”. At a minimum, the only reasonable interpretation of this is that Card is suggesting something like this will unfold. Just as he predicted the fall of the USSR but not the timing or exact method, his prediction about a totalitarian US seems to be in earnest, although the specific route he outlines is just intended as an example. But not an example “about writing and imagination” (as you put it) but about real-world events. He goes on to accuse the editorial board of the NYT and WaPo of hating democracy and being fascists at heart, and this is after we’ve wrapped up the thought experiment. That, along with the argument that Benghazi could have been thwarted, are Card’s sincere beliefs.

The incident that you dismiss as an exercise in imagination Card calls plausible no less than three times in one essay, and also compares to real-world historical predictions. He intermingles it with straight-up conspiracy theory talk, and then concludes with this enigmatic line:

Whenever someone says “just kidding” you can be sure that–to one degree or another–they weren’t.

If anyone else is curious, the full text is here: http://www.ornery.org/essays/warwatch/2013-05-09-1.html

It’s from May 2013.

I just can’t let the confluence of my two favorite subjects just lie there without redress. I know I’ve been accused of being too glib on this subject before, so I will try my best to give you a truly tolerant response. I assume Card and yourself fall into the same category of people on this subject as my parents who are both good, kind and loving people, who really take to heart Christ’s message of hate the sin, love the sinner. I have gay friends who have been shown great kindness by my parents in times of need, but I have also been told that if they were to move and rent out their house, they should have the right not to rent to a gay couple. What I take from this isn’t that my parents are bigots who deserve to be publicly shamed (certainly not what I’m trying to do here), just an example. But I do feel strongly that they and you and Card are wrong about this, and I do think the thing that is missing is empathy.

I think the quote about adolescents is a good and important one because it begs the question, what are gay people supposed to do “when the loneliness becomes unbearable.” I’m not overly concerned with the question of whether or not gays are born gay because of their genes or because of hormones in the womb, or even if it’s just early life experiences that get you there, but the reality for the vast majority of those in the gay community is that as far back as they can remember they have been attracted to the gender they are attracted to. And the few I’ve known who didn’t describe their experience this way have described a sort of neutrality that was ended when they found a specific person who ended the “unbearable loneliness” for them. So when you deny people a right to marry, you deny them (by Card’s own description) the right to become a “full citizen” and force them to forever remain “ a stranger, a child, an outlaw, a slave, or a traitor” and to never become “truly adults” through no fault of their own. What would you do in their shoes? What happens when you show up with the person that makes you feel rooted to rent a house and the person won’t let you rent the place or teach at that school? The lack of empathy that I see and what I think people may be too quick to call bigotry, is that its hard for me to reconcile that person who gives bread to a hungry man no matter who he loves with the one who let him mature into a true adult.

When I first hitched my wagon to the gay rights parade I tried to convince people on my side that they shouldn’t over reach that they should push for domestic partnerships, because really why did it matter if you got everything the same and called it something else? But I was always greeted with distrust and sometimes hostility. I didn’t really understand it then because I like to think everyone should think strategically about these things. But if they were willing to take that sort of deal they’d be guilty of just being the libertines you’ve often accused the modern liberal of being. So I’m not sure where your and Orman’s skepticism about the responsibilities of marriage being important to the gay community are coming from. It seems a little much to ask them to talk about the ‘gay responsibility movement’. The voting rights movement didn’t spend much time talking about the responsibility of jury duty, immigrants who have lived here a majority of their lives don’t talk a lot about being excited to pay taxes, they talk about equality because it implies equality of freedom and responsibility.

So ignoring the real life implications and getting to what I think the truly most interesting question raised by this, what about the children of the mind of Christ? They have abstinent marriages. Doesn’t that sort of undercut the importance of sex in a marriage altogether, at least in this world, according to Card’s own ideology sex is superfluous to a marriage, so why should sex with the wrong set of genitals suddenly become more important than all of the other parts of the contract. My marriage to my wife won’t end if my genitals cease working, it has been established multiple times (and I’m not kidding) that we will stay married and love each other even if one of us is magically transformed into a cricket. I get to make this commitment or not make this commitment as I see fit, and I will be judged worthy or unworthy of respect by my family and her family and my community based on how I keep that commitment as will you and Ro, as will Lanaya and Ashley. So, I am just left to wonder if members of the Filhos da Mente de Cristo are allowed to marry members of the same gender, and if not, why?

Saying that the administration did nothing to defend the embassy in Benghazi isn’t really a conspiracy theory; it’s more or less true (credible evidence being subjective–I’ll side with the marine who tried to call in the airstrike). If he said they deliberately chose not to defend it as part of a larger scheme to serve the interests of some group or other, that’d be a conspiracy.

But his point was not that he thought any of this was happen. When he says it could happen, that’s a statement about the present, not the future. Had he written the article in question ten years ago and about Bush, I suspect it would have gotten a very different response. As it stands, it’s an article about the current President, and his perceived regard for rule of law and the constitution.

Ryan-

That’s not the conspiracy theory part. The conspiracy theory part is the statement that they could have done something. It’s a conspiracy theory because 1) it implies a vast coverup and 2) it contradicts every reasonable known fact.

I think you’re de-emphasizing the extent to which Card’s piece is designed to serve as a warning against a perceived real-world danger, but at this point I think the facts are too squishy to be amenable to further debate.

Daniel-

There isn’t enough honest, heartfelt, and kind discussion about this topic from people who see things differently. So first: thanks for you post.

I think empathy is very important, but I don’t think it’s the only important consideration. I know and understand that being gay is not a choice. I realize that gay people are born that way, and can’t change. I can’t say “I understand” and I won’t insult people who have gone through really hard experiences by pretending otherwise, but I can say that I have seriously thought about what it would be like to grow up gay, and that imagining that life moves me. I’ve watched some heartfelt expressions of the pain of growing up gay, such as the recent video about the little straight girl (in an alternate, homonortmative universe) who ends up killing herself. There’s also a serious, short film about Bert and Ernie that ends with Ernie’s suicide. (It may sound like a joke in text, but it’s actually a stark and serious film.) Again, I’m not trying to say “I get it.” I’m just saying that I know that I don’t get it, but that I do try to understand.

One of the most influential people on my thinking, by the way is Josh Weed. You might have heard of him. He came out as a gay Mormon in June 2012: http://www.joshweed.com/2012/06/club-unicorn-in-which-i-come-out-of.html His story is very unique, however, since he’s married to a woman (who knew he was gay before he got married to her) and they have kids together and such. He’s very careful to point out that he’s not saying everyone else should do what he did and find a way to make a heterosexual relationship work despite being gay, so that’s not why I’m linking to it. He’s just a voice that carries a lot of weight with me, since he’s writing from within the conservative Mormon tradition about the experiences of growing up gay in Utah and the pain, heartache, and confusion that went with that.

The point I’m making, and it relies on you taking my word for it ’cause I can’t prove it, is that despite my empathy with gay folks (an empathy I continue to try and develop), I remain opposed to gay marriage, at least within the confines of the current debate. Like Card, I believe passionately that marriage is the most vital institution for society. The current arguments for gay marriage threaten that institution by reformulating marriage as a right instead of as a duty, and also by undermining the central role of children and monogamy. If the gay rights community were overtly committed to marriage-as-duty, monogamy, and to the primacy of child-rearing, then I honestly can’t say what my position would be, but I’d be much, much more sympathetic and possibly even actively pro-gay marriage. (And I realize that some individuals with in the movement do affirm these principles, but they are not central or universal.) I understand that marriage offers things that gay people want, and that their lives are less full without it, but there is a cost. I am acutely aware of how easy it is to say that the cost doesn’t justify the benefit when I don’t bear the cost. I get that, but I can’t change my sincere opinion. I can do my best to try and be fair, but that’s all I can do.

I also think there’s a question of who we’re empathizing with. After no-fault divorce, the divorce rate jumped dramatically. Millions of children who may have had stable families (many studies show that couples considering divorce who stay married are subsequently happy with that decision) instead came from broken homes. The costs of divorce are staggering. Who empathizes with them? Empathy is only as reliable as it is universal.

I have similar feelings about abortion. A lot of pro-life advocates do not freely admit the cost of a pro-life society on women in crisis pregnancy. There’s a failure of empathy. I’ve had friends who have been raped and had life-threatening ectopic pregnancies. Again: I can’t say “I understand” because I saw this as a supportive friend, but it makes me conscious of the cost of crisis pregnancy. But I still believe in a moderate pro-life position because I believe that ultimately abortion (especially as practiced today) is not truly in the interests of women, and also because I consider the fate of her unborn child in addition to (not instead of) her plight.

When it comes down to it: I think that a traditional society is going to relegate the LGBT community to the status of outsider. Partially, I think it’s necessary. But partially I also think it’s not that bad. Outsiders sometimes have privileged status. Paglia talks about shaman and artists, both of whom traditionally come from outside the main culture. I think the gay community, even with gay marriage, is its own community. Do they truly want to assimilate? Set aside their gay identity? I don’t think they do. I think that being different is a part of what the gay community takes pride in.

Speaking broadly, I think one of the biggest differences between liberals and conservatives across a whole range of issues really comes down to this one question: how do you react to unfairness that seems to be intrinsic to the world we live in. Some people get cancer. Some don’t. It’s not fair. From my perspective, liberals seem to embrace unrealistic policies to try and eliminate the essential unfairness by, for example, embracing universal health care as a way to make life fair. Even if we had universal health care life would not be fair. A cancer diagnosis doesn’t go away because you’ve got great coverage. So, as a conservative, I take the fundamental unfairness of live as axiomatic. Life is full of random shit that just happens, and it’s a waste of time to try and make it go away. The best policy is to mitigate it. (Please note: my point is not “what’s the best policy: more capitalism or more universal coverage?” My point is that it’s a different philosophical approach. I don’t think making life fair should be the only goal of a healthcare policy. I think tolerating some degree of unfairness if it means better outcomes for everyone is a valid approach to take.)

Being born gay makes you an outsider. I sort of take that as just axiomatic. Only a small percentage of people are born gay, and since sex is integral to our experience as mortal creatures, that’s going to make for a different life experience. I would rather work within that fundamental paradigm to ensure gays are loved and respected then embrace what I see as a kind of denialism that pretends it just doesn’t matter or is totally inconsequential. We’re all people, yes, but part of the human experience is awareness of the things that make us different.

Being gay is one way of being different. Being different can be hard. But I think to some extent that is a blessing. It provides unique perspective and experience. Perspectives and experience that are good not just for the individual, but for society. (Again: I know that’s easy for me to say. But I can’t do anything about that except try to account for it as best I can.)

As for your last question: I don’t think it came up in the Ender’s Game universe. I think it was assumed that the priests and nuns in the Children of the Mind of Christ order were paired heterosexually. And I think that’s not because Card thought sex was superfluous, but rather because he thought it was an expression of a more fundamental dichotomy of gender. That there’s something about different genders that defines marriage, even when there isn’t any sex. But, like I said, I don’t think it was covered. He does have gay characters in other situations, however, but that’s from a different series.

Are people born gay? Are we born Christians? Atheists? Marathoners? Are we born alcoholics?

I’d just like to point out that’s a pretty fundamental assumption you make there, and a pretty debateable one.

Matt-

It’s not an assumption. An assumption is something you accept without question at the beginning of an argument. My belief that people are born gay is a conclusion. It’s a position I came to after being convinced by the research I did and the conversations I have.

Sexuality is a malleable and complex thing. It’s not strictly binary. So the “born this way” argument is a simplification, but it’s more accurate than calling homosexual attraction a choice or a lifestyle and I believe that for many in the gay community it is the reality.

A friend on Facebook, and someone who knows the Card family, forwarded me the eulogy Card wrote for his son who died at the age of 17 in August 2000. It’s an incredibly moving and powerful piece, and once again shows how the concepts of otherness and empathy have played a role in Card’s life and writing. I don’t think it proves any definitive point, but I think it provides another perspective on the man. And that, after all, is what this post was originally and primarily about.

http://www.hatrack.com/misc/charlie/bio.shtml

I don’t mean to insinuate you hadn’t thought that position of “born gay” through, I simply feel that’s something relevant and pivotal to your post and argument. Especially in light of that being a fundamental difference between your position and Card’s.

I think you mistake the difference between liberals and conservatives. You think conservatives accept unfairness and liberals don’t. I think conservatives accept unfairness not only from the world, but from themselves, while liberals try not to be unfair. Sure, a diagnosis of cancer is inherently unfair, but we don’t have to make it more unfair by only caring for those who can afford it (usually through no merit of their own, but through the same unfair vagaries of the universe). We can choose not to be unfair ourselves, we can choose to be better than that. It is what Christ teaches in the bible (I am an atheist, but that message is clear for anyone who actually reads the new testament), and I believe that it is what most of us feel, deep in our hearts. You can reject the idea of public health care when it’s statistics, but not when you are faced with a child who dies due to not being able to afford medical care… you can reject gay marriage, but you can’t do so when you face a partner who is denied the right to be by his loved ones side as his loved one dies (of if you can, you might just be a monster). I personally believe the state should have no hand in marriage at all, but if we are giving different rules to married people than to unmarried ones, then we need to extend those rules (both rights and responsibilities) to everyone. In a hundred years this idea will seem as valid as the idea that white people and black people should not be allowed to marry, and both you and Orson Scott Card will find yourselves on the wrong side of history.

Yeah, matt, everything about what makes us who we are is very debateable, but there is a societal understanding in general that we aren’t 100% responsible for our actions before a certain point, whether thats 8 for mormons or 13 or about 27 in my case, almost every LBGT person I’ve known has known before then. I still remember watching chip and dale rescue rangers when I was a little kid because I had a little crush on the girl mouse “Gadget”, but some people just had a crush on Chip.

Speaking of facebook, the discussions about this article I’ve seen there are all hung up on your brief mention of ‘no fault divorce.’ Mostly, you’re getting attacked for daring to think something so self-evidently good as no-fault divorce might have had bad consequences. I tend to agree that no-fault divorce was a bad idea, but then I’ve been through an unnecessary divorce, so I may be somewhat biased.

The broader difference is that, while I may critique what I see to be liberal tendencies, I’m at least willing to give the benefit of good faith. I think the tendency to focus on fairness is compatible with being a decent human being. So nothing about my argument implies or assumes that liberals are anything but decent human beings. You, on the other hand, are perfectly comfortable writing off 1/2 the country as jerks who don’t even try to be fair.

OK.

Yeah, I’ve been following at least one long thread, but have managed to refrain from weighing in. It’s an odd feeling, having spent so many years debating in the comments on articles, to be watching it from the other side.

The debate about divorce really misses the point of my post (it’s less important whether or not no-fault divorce is a net-benefit or net-harm, and more important to understand that Card probably believes it’s a net-harm), but that’s why they call these “hot-button issues”. Once people see them it’s a like a bull going after the matador’s cape.

It is a very hot button issue. The one time I dared broach the idea of no-fault divorce being a bad thing on a blog, I got several comments from people who had been in terrible marriages that were offended that something that saved them a lot of grief (being able to get out of the marriage easily) was a net-bad. My feelings and the grief it caused me and my kids weren’t important to them (one commentator even went so far as to come *this* close to stating I must be an abuser because only abusers would be against no fault divorce). I finally decided it’s just too emotional an issue – for me the divorce is a wound that will never heal (and it seems like that for my kids too), but for others it was a needed balm. We wind up arguing passionate emotions, regardless of where the overall truth may lie.

You were the one who said you weren’t trying to be fair… as to me writing you off as jerks, quit acting like a jerk and I will stop calling you one. Sorry, but that’s truth. It is a controversial issue… in the same way black people marrying white people was once a controversial issue, and it is very hard to look at the people who argued against mixed race marriages now with any form of sympathy.

This isn’t a gay rights issue, it’s a human rights issue. And no, civil partnerships aren’t good enough. If you want gay people to have civil partnerships, then that should be the only thing that is legally recognized. Look, marriage in a church is different, and there is no movement to force religions to perform gay marriage, it is up to the individual church. However, the legal entity of marriage is one with serious and far reaching implications. As such, it truly needs to be equal. To fight that is in fact to be a jerk.

Good post. Something I have thought about for a while.

What is the probability that marriage remains a central pillar of civilization if the gay marriage movement is successful? Probably 0. You can look at the places where gay marriage is already legal. It is nor necessary that gay marriage be part and parcel of the devaluation of marriage, but in practice it is central.

What is the probability that marriage remains a central pillar of civilization if the gay marriage movement is defeated? Probably quite low as well, but a lot higher than 0.

I support the abolition of marriage myself, and so am a tacit support of gay marriage, but I understand the opposition to gay marriage; it is not unreasonable.

Card is a bigot. To say otherwise is to lie. You are a bigot as well. And stop using the phrase “gay marriage”. It isn’t “gay marriage”. It is marriage. Marriage equality. You are opposed to me being treated as your equal, therefore you are a bigot. You do not debate human rights.

I had that quandary with Orson Scott Card over ten years ago when I came across his online political columns. This was before homosexuals were lumped in with his his condemnations of feminists, liberals, Democrats, Muslims, and those outside of the Christian-Jewish-Mormon community who did not share his views and support Bush/Cheney and their wars and “coddled terrorists.” For someone who explains empathy so well in his early novels and may exhibit it toward his friends he is a public intolerant hating extreme partisan bigot in his online writings.