President Obama made a surprise call to increase the national minimum wage to $9 per hour. Is that actually a good idea? Becker and Posner took the issue on directly. Becker writes in a measured, but skeptical tone:

The two main issues debated are the effects of a higher minimum on employment of the low skilled, and its effects on the degree of poverty. Both theory and evidence indicate that higher minimums reduce employment for teenagers and other workers with low productivity, and that it does little to alleviate poverty. Neither conclusion, however, is without controversy, especially the employment effect.

He adds at the end that since recipients of minimum wage are also the customers of companies that have to bear the brunt of paying their workers above market rate: “low-income families are hit by two bullets: some of their members find it harder to get jobs, and they face a higher cost of the goods they consume.”

Posner weighs in with skepticism as well:

The proposal will not commend itself to most economists who study the economic consequences of minimum wages. They make three principal arguments: minimum wage laws reduce employment (and efficient resource allocation) by pricing labor above its market rate; the laws do not reduce poverty, because most beneficiaries of minimum wage laws are not poor; and as a means of reducing economic inequality, such laws are inferior to the Earned Income Tax Credit (i.e., the negative income tax). I will try to assess these arguments.

His conclusion is that, since we know so little and the proposed increase is so large, we should start with a more modest increase. He also suggests that indexing to inflation is a bad idea:

And I don’t think indexing the minimum wage to inflation is a good idea; should inflation surge, which is always a possibility though not (it seems) an imminent one, an equal increase in the minimum wage might contribute to an inflationary spiral.

I actually found an interesting article by Michigan macro professor Miles Kimball which addresses the controversial employment effect. Kimball cites work by Isaac Sorkin (an incredibly brilliant grad student who started the PhD program at the same time that I did) who explained that the employment effect might be much greater than expected; it just takes a long time to go into effect. A lot of companies engineer their production around assumptions about wage, and when the wage assumptions change (e.g. minimum wage goes into effect), they only gradually move to less labor-intensive production because of adjustment costs. In other words: they don’t go out and buy brand new machines on day 1, they just gradually phase out machines and processes to shift towards using fewer employees. That’s more reason to suspect that a minimum wage hike will do more harm than good, and indexing it to inflation would compound the problem.

And then there’s Greg Mankiw (very respected macroeconomist, but also openly Republican) who asks the simple question: why $9? Mankiw’s point is that if minimum wage is a magic wand to increase the salaries of the poor, why wouldn’t you you jump all the way to $25 (equivalent to the current median income of $50,000 for 2,000 hours/year)? Some mysterious force suggest we shouldn’t go too high, but the President isn’t talking about it. What is it? Good question.

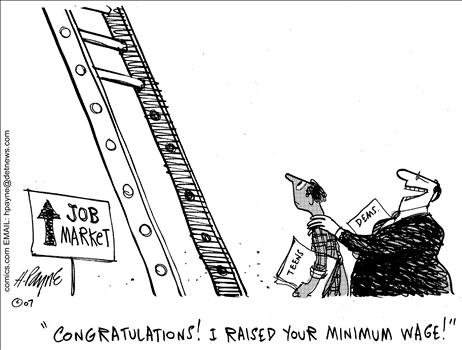

My own take is that it is socially useful to have jobs available that pay less than what a person could live off of, primarily for teenagers to gain initial job experience. You need to have a bottom rung of the ladder, a place where you can go, start a resume, and use it as a launching pad for better jobs. I got my first minimum wage job when I was 14, and I’ve worked ever since: janitor, file clerk, bus boy, dishwasher, etc. I didn’t life myself up by my bootstraps, so a starter job is not enough. But it does help. Taking that away won’t help anyone. Fighting poverty and reducing income inequality are valid goals, but this is not a valid strategy to accomplish them.

http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=941970