Malcolm Harris’s The White Market is an essay about race, consumerism, and the television show Breaking Bad. It’s an impressively smart piece of analysis, but it’s also an example of cleverness getting in the way of insight. More particularly, it’s an example of how anti-discrimination can go awry.

The central argument of the article is that in order for Breaking Bad to attract advertisers it has to depict the drug trade in ways that are not only highly unrealistic, but that are unrealistic in very specific ways. In short: Walter White makes meth that is pure. He’s a scientist using industry-grade pharmaceutical techniques and equipment to make exquisite product that he sells to that demographic known above all else for its taste and discernment: meth-heads.

As Harris observes:

The idea that people will always pay more for purer or small-batch products makes a lot of sense to demographics used to paying more for quality gimmicks — conveniently, the same demos advertisers pay a premium for. But it doesn’t make sense for the consumers Breaking Bad so sparingly depicts. When we do see White’s ultimate customers, they’re zombies: all scabs and eroded teeth. We’re not talking about impulse buyers or comparison shoppers here; it’s a textbook case of what freshman economics students call inelastic demand. As Stringer Bell told D’Angelo Barksdale in another show about drugs, in direct contrast to what Walter claims, “When it’s good, they buy. When it’s bad, they buy twice as much. The worse we do, the more money we make.”

So far so good: if you want Dodge to come to you and ask for product placements you have to turn Walter White into an artisan. He’s the indie micro-brewer of New Mexico’s meth market. But then Harris gets to the second phase of his essay:

Which brings us to the other thing that sets White and Pinkman apart from their competitors: color. And I don’t mean blue.

The white guy who enters a world supposedly beneath him where he doesn’t belong yet nonetheless triumphs over the inhabitants is older than talkies. TV Tropes calls it “Mighty Whitey,” and examples range from Tom Cruise as Samurai and Daniel Day Lewis as Mohican to the slightly less far-fetched Julia Stiles as ghetto-fabulous. But whether it’s a 3-D Marine playing alien in Avatar or Bruce Wayne slumming in a Bhutanese prison, the story is still good for a few hundred million bucks. The story changes a bit from telling to telling, but the meaning is consistent: a white person is (and by extension, white people are) best at everything.

This, for me, is where the thread of the piece begins to unravel. It’s not that Harris’s racism-explanation is unusually bad. I’ve chosen this essay precisely because it’s so typical of a fundamental problem with anti-discrimination. And that is this: whenever there’s an racially unfavorable outcome, nefarious motivations are assumed to be the cause. According to Harris the fact that Walter is white and his enemies (such as the Mexican drug cartel) are not is a deliberate play to racism. As he writes: “The drug world is a convenient setting for selling white supremacy because it allows for a white underdog in an openly racialized conflict.” And, just at the conclusion of his essay, he writes:

The U.S. is still very much a white supremacist country, but classic cowboys-kill-Indians narratives don’t play with wealthy viewers or the critics who help determine those tastes.

That’s an interesting juxtaposition: wealthy (presumably white) viewers and critics wont’ stand for overt racism, but as long as you can be subtle about it, racism sells. Or does it?

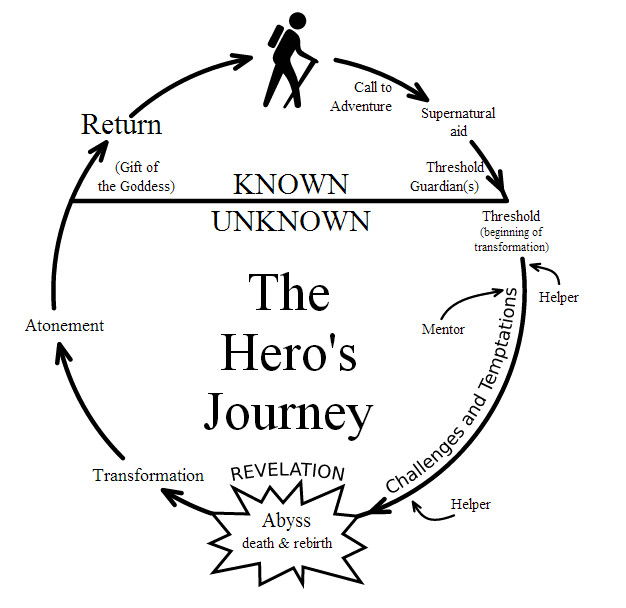

Here’s the problem I have with the Mighty Whitey trope: what if it’s not actually about white people being better than non-white people? What if the real motivation is the hero’s journey or monomyth. According to Campbell’s influential The Hero with a Thousand Faces there’s a basic pattern found in narratives across many cultures and times. A fundamental aspect of the monomyth is that the hero leaves what is familiar, ventures into uncharted land, and has adventures there before returning home triumphant. What kind of people live in uncharted land? Other people. Now if your hero is white–and in a country that is nearly 80% white your hero will often be white–the people who are different are going to be not-white. Sometimes they will be Indian (Last of the Mohicans, Dances with Wolves), sometimes they will be Japanese (The Last Samurai) and sometimes they will be really tall blue people in the Alpha Centauri star system (Avatar). But sometimes your hero will be black the other people will be white (Pursuit of Happiness) or Asian (the 2010 remake of The Karate Kid). Sometimes your hero will be Arab and the others will be Vikings (The 13th Warrior) and sometimes your hero will be black and the other will be white aliens (Deep Space Nine). What if the dominance of the white version of this story isn’t about a belief that white people are better? What if it has nothing to do with white supremacy? What if it’s just about a culturally universal story being told by people who are predominantly white? What if the appearance of racism does not actually stem from racism. Does that matter? I don’t think it makes the problem go away, but I do think it matters.

If you’ll notice in the above chart, the appearance of helpers is also a fundamental aspect of the hero’s journey and also occurs after the hero leaves the known and enters the unknown. This is why the Magic Negro is also a trope: the kind, elderly black folk who help white people along their winsome way. Of course sometimes they aren’t black, sometimes they are Asian karate masters (Mister Miyagi) or short, green aliens (Yoda). And of course if the hero is not white, then the helper can’t be white either, which is why in The Karate Kid update Will Smith’s’ kid gets a wise Asian (in this case, Jackie Chan) for his mentor.

Does the fact that the Magic Negro and Mighty Whitey tropes might be innocent mean that they are perfectly acceptable? Not necessarily. But I do think it’s very telling that if the white character is better at everything (Mighty Whitey) that’s bad, and if the non-white character is better at everything, or at least invaluable to saving the white character (Magic Negro), that’s bad too. This illustrates one of the real dangers of cracking down on every instance of the trope as proof-positive of “white supremacy”. If it’s demeaning to have the white character show up and save the non-whites and it’s also demeaning to have the non-white character show up and save the white character then it sends a message that no matter what you try to do you’ll be wrong.

That has two sad consequences. On the one hand, most white people simply refuse to talk about race seriously. Unless they are buried eight-layers deep in rhetorical and political armor from the progressive anti-discrimination movement, they simply will not open their mouths honestly because there’s no upside. Even if they really want to do good, they are terrified of making an innocent mistake and getting attacked for it. On the other hand, a minority of white folk go the opposite direction and are intentionally offensive. Whether it’s 12-year old trash talkers on Xbox Live who pick homophobic, anti-Semitic and racist slurs precisely because they are taboo or right-wing talking heads who intentionally use incendiary rhetoric to draw fire from the left, these behaviors are exacerbated by the kind of damned-if-you-do, damned-if-you-don’t nature of racial conversations in the US.

I’m not excusing any of this, by the way. I’m not saying that we should all feel sorry for upper-middle class white people because they are uncomfortable talking about race, as though that one consideration suddenly equalized the scales of white privilege. And I’m not saying that offensive language designed to hurt is anything but disgusting. But I do think that the idea whoever suffers the most has no obligation to try and reach out to those who suffer less to foster mutual understanding is dangerous. The reality is that white teenagers who use discriminatory language are not doing it because they are bigots. They don’t hate Jews or black people, they just want to be offensive. But when they spend hours on end using such vile language, then they become bigots. And the idea that conservative politicians use coded language to communicate their racist ideology is a figment of liberal hysteria. Conservatives are doing one of two things. Either they are actually saying exactly what they are saying, with no attempt to covertly discuss race, or are they deliberately choosing terms that are not technically discriminatory (in their view), but which are designed to outrage liberals so that liberals will attack. The conservatives then use those condemnations of non-discriminatory (again,in their view) remarks as proof-positive that liberals are all reverse-racists.

For a concrete example of this loathsome tactic, look at Dinesh D’Souza’s use of the term “lactation man” (meaning: to make white) to describe President Obama. Although he takes pains to describe why it’s not actually racist (e.g. doesn’t presume the inferiority of blacks), it is obviously designed precisely to convey that impression. Additionally, it’s a two-fer, since it’s vaguely sexist as well as racist. I remember reading in the papers many years ago (when I was in high school) of someone who had been fired for using the word “niggardly” in its correct (non-racist) sense, but you get the impression that in 2013 anyone who uses that term would probably be intentionally goading racial sensitivities just to make a point.

For a concrete example of this loathsome tactic, look at Dinesh D’Souza’s use of the term “lactation man” (meaning: to make white) to describe President Obama. Although he takes pains to describe why it’s not actually racist (e.g. doesn’t presume the inferiority of blacks), it is obviously designed precisely to convey that impression. Additionally, it’s a two-fer, since it’s vaguely sexist as well as racist. I remember reading in the papers many years ago (when I was in high school) of someone who had been fired for using the word “niggardly” in its correct (non-racist) sense, but you get the impression that in 2013 anyone who uses that term would probably be intentionally goading racial sensitivities just to make a point.

So no: I’m not defending things-as-they-are. But I am saying that the current practices of the anti-discrimination folks (as I see them, and as exemplified in the Harris essay) are clearly not productive responses. By insisting on seeing bad motivations even where none exist, they leave no safe zone for communication. By interpreting all differences as evidence of discrimination and yet also insisting that people identify with specific race, gender, or sexual orientations they ensure a perfect catch-22 that ensures no forward progress can ever be made.

I think that we ought to be more tolerant of unintentional and mild forms of discrimination. First of all: studies indicate that this is pretty much genetic behavior. Nurture Shock, for example, explains how in the absence of positive training about diversity young children will self-segregate by race all on their own. We all define groups based on physical appearance, and we all have an unconscious affinity towards those groups. Since this is apparently genetic, it’s not going to change in the immediate future. Treating this kind of latent, persistent discrimination (which everyone engages in) as akin to white supremacy creates a standard no one can hope to attain and discourages real progress because everyone has to live in denial for their own safety.

Secondly, some forms of discrimination really are mild. This doesn’t mean that they are acceptable, but it might mean that diminishing returns mean that at a certain point you do more harm than good in trying to stamp them out. Consider, for example, the widespread preference for taller people as leaders. That’s why the stages are carefully designed in televised presidential debates to give the appearance of equal height. That’s nice for presidential candidates, but as a man who is only 5’7″ I will live with that discrimination my whole life. I’m not equating that to race-based or gender-based discrimination, but I am saying that all discrimination counts, not just the most severe. For my entire life I will be overlooked for promotion and leadership positions if I’m next to someone taller. It’s unfortunate, but it’s life. I don’t support any policies or awareness campaigns to change it and, as I’ve said, it’s not like I think I’m coming out on the losing end in 21st century America all things considered. I just don’t think we can afford to be puritanical about discrimination because we’re probably never going to reach perfection. That might not be OK, but it is reality.

I’d like to see a recognition that we can have a healthy, positive, vibrant society while still having some mild discrimination. We don’t have that society today. Discrimination in our society is not mild today. But I think that an almost fanatical desire to purge discrimination at all costs is actually making progress slower rather than faster.

I certainly don’t have all the answers to discrimination in our society, but I think that part of the solution begins with de-militarizing the rhetoric. It’s not a good thing that the hero’s journey has been implemented in a way that tends towards Mighty Whitey, but it’s not proof of white supremacy either. I know that the horrific historic injustices and continuing staggering inequality make it hard not to be passionate about these issues. I know that we continue to have a racially skewed society, and that when being white is obviously correlated with having an easier life it’s not a welcome proposition to start talking about having empathy for those who are lucky. It’s not fair, and I acknowledge that. But sometimes we let fairness get in the way of progress, just as sometimes we let the perfect get in the way of the good.

What I’d like to see, more than anything else, is an admission that deep down we’re all just people. That rather than living in distinct silos of “gay” or “straight”, “man” or “woman”, “black” or “white”, we actually have a root commonality: human, that is deeper and more integral than our differences. I don’t say this to deny the differences or pretend the problems don’t exist or that all groups are equal. I say this because I know those things are not true, but I believe that only on a common foundation can we ultimately make them become true.

Another great post, Nathaniel!

Dangit! You’re taller than me! *grumble grumble*