There’s an old rule: “If you don’t have anything nice to say, don’t say anything at all.” I think we could retrofit that for bloggers as: “If you don’t have anything new to blog, don’t blog at all.” The trouble, of course, is that in that event most of us would stop blogging.

For example, I’ve wanted to write a post about the myth of evil for quite some time. What I mean by this is the belief–reaffirmed by media in the wake of every horrific crime–that evil acts are committed by evil people, and that evil people are a different kind of entity than good people. In other words, it’s the opposite of what Sirius Black tells Harry Potter: “The world isn’t split into good people and Death Eaters. We’ve all got both light and dark inside us.” Contrast that with, for example, the hopeless attempt to use DNA to find out what caused the Sandyhook shooting. That is the 21st century equivalent of looking for demonic possession: an attempt to reaffirm the myth that those who do great evil are essentially different from the rest of us.

When I started writing the post, however, I decided to do a quick Google search first. Turns out, there’s already a book: “The Myth of Evil explores a contradiction at the heart of modern thought about what it is to be human: the belief that a human being cannot commit a radically evil act purely for its own sake and the evidence that radically evil acts are committed not by inhuman monsters, but by human beings.” That took the wind right out of my sails. I don’t know if the book actually makes the same specific arguments I was going to make, but I would feel like a fraud for not reading it first to find out. And if I have to read a book before I write every single blog post…

This isn’t an isolated incident. When I was 10 years old I wrote a piano song of my very own, and then heard the melody played on the radio a couple of days later. Once I spent an entire semester working on a complex systems project that turned out to be just recreating the basics of reinforcement learning. I’d never heard the term before, and neither had most of the folks in the class, but when I gave my final presentation one of the other students pointed out that there was already a textbook. In grad school I spent a lot of time thinking about economic equality and came up with the idea that it had to be measured in terms of opportunity to make any sense. Turns out, that’s part of what got Amartya Sen his Nobel Prize. Everyone’s heard the idea that there are no new stories, but there are new facts and new theories. I just keep thinking up old ones instead. So: why blog?

The first reason is that even if I don’t come up with completely new ideas, I can still (I hope) share things that are new with my audience. And the second is that I think being a constructive part of the conversation on important issues is a kind of civic duty, sort of like voting. Both of these ideas come from the way that I believe ideas spread through society.

When I was a senior in high school a took a college course in ethics. One of the papers we read was Judith Jarvis Thomson’s 1971 A Defense of Abortion. One of her central thought-experiments involves the idea of a woman waking up one morning to find that in the night a surgeon had attached a concert violinist. If she severs the connection, the violinist will die, but if she allows the violinist to remain attached to her for nine months he can be removed and live the rest of his life independently. Thomson’s point was that this proves abortion should be legal even the unborn human being is viewed as a person. The thing that was interesting was that, as a senior in high school, I was already perfectly familiar with the thought experiment even though I’d never read the paper or even heard of it.

What’s more, as I continued to debate abortion for years, I would hear the same thought experiment come up again and again and again, but often when I asked the people if they’d read the paper they would acknowledge they’d never heard of it either. No one seemed to be really sure where they first heard the idea (I can’t remember that either), but it’s just sort of out there, spreading through society by osmosis. By this time, the thought experiment is nearly a half-century old, but it’s still new every time someone hears it for the first time, and in many ways it’s much more relevant today than it was in 1971 because of the way the abortion debate has changed.

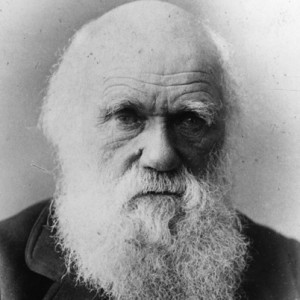

This is just one specific example of the way I believe ideas interact with society. Someone, often a leading expert or professional academic, develops a theory. Then that theory, or often a simplified, warped, and even broken variant of it becomes an independent meme and takes on a life of its own. These potent intellectual building blocks become an integral part of the way people make sense of the world around them. They get used and reused in the service of all kinds of narratives that may be unimaginable or directly contrary to the intentions of their originators. For example, Darwin took great pains to explain that natural selection is not an optimization routine. That has two components. The first is that natural selection doesn’t mean you have to be the faster than the bear, it just means you have to be faster than the other guy. (It’s a satisficing routine.) Secondly, there’s no objective “bear” to be faster than: natural selection is contingent on environment. But even though Darwin understood that evolution isn’t an optimization routine, that hasn’t prevented others from hijacking the theory of evolution in precisely that way. Social Darwinism is a great example:

Social Darwinism is an ideology of society that seeks to apply biological concepts of Darwinism or of evolutionary theory to sociology and politics, often with the assumption that conflict between groups in society leads to social progress as superior groups outcompete inferior ones. [emphasis added]

There’s one other theory I have to explain before I can rationalize my blogging, however, and this one has to do with how people view the influence of individuals on the unfolding of history. There are basically two extreme views on this. According to the first, history can and frequently is determined by the unique character of irreplaceable individuals. George Washington is a great example of this, because in handing over power after serving his first term as President of the United States he relinquished authority in a way that very, very few others in history have ever chosen to do. So his action was crucial (he inaugurated the peaceful transition of power that has continued in unbroken succession from that day) and there’s a reasonable argument that no one else (or very few others) would have chosen to do it.

According to the second view, however, history unfolds like the Mississippi River following its course, and the actions of mere individuals are of no more consequence than individual ants trying to redirect those muddy waters. It’s impersonal, abstract forces that dictate history, and we just invent narratives that give credit to individual human beings after the fact. Christopher Columbus would be a good example of this theory. The argument would be that the real explanation for the “discovery” of the New World had nothing to do with his individual character and everything to do with the level of technological advancement and economic and political conditions in Europe. Someone could have discovered the New World before him (indeed: some did) and it wouldn’t have mattered, and if he hadn’t done in 1492 than someone else would have in 1507 (or whatever) and basically nothing would have changed except some names and dates.

I believe in a hybrid of these two. I believe that impersonal, abstract forces are just a convenient way of thinking about the collective actions of individual human beings. Which means that while individual actions seem to be irrelevant when viewed individually, in reality there is nothing else going on. There’s another simple example of this, and it is voting. Economists and mathematicians will smugly tell you the votes of individuals don’t matter, and in a technical sense they are correct. If you don’t vote, there is almost literally a 0% chance that the outcome of an election will be changed. But if everyone actually did what was rational according to individual incentives, no one would vote. (Actually, things get tricky because the fewer people vote, the easier it is for an organized cadre to seize power, but the basic rule applies.)

What does all this have to do with blogging? Simply this: I think that the course of history is determined basically by what people believe, and that what people believe is the outcome of billions of individual conversations where those recycled memes are frequently deployed as the building blocks of competing narratives. In this sense, I see humanity itself as one giant, complex system. Almost like an organism. And we’re metabolizing knowledge and information, turning it into practices, traditions, and institutions that will either help or harm us in our day-to-day lives.

I don’t think that I have the ability to necessarily introduce new facts or theories or analyses to the entire system, but I do have the ability to contribute in a tiny way (just like voting) to how the facts, theories, and analyses that already exist are discussed, ignored, believed, doubted, combined, or deconstructed. In one sense this is incredibly liberating: I don’t have to come up with something completely new. I don’t even necessarily have to come up with something that is True.

That last line requires a quick tangent. Of course I have an obligation to express what is true, but I believe Obi Wan Kenobi was right when he told Luke Skywalker that “many of the truths we cling to depend greatly on our own point of view.” I can strive to be honest from my point of view, and also to change my point of view, but I don’t think I’ll ever have the perfectly objective, all-considering point of view necessary for Truth. But I don’t think that I need to have the final answer in order to contribute towards the ongoing, collective process of moving humanity as a system towards better answers.

So, now I’ve apparently gone from “no one should blog, ever” to “everyone should blog all the time”. Overkill?

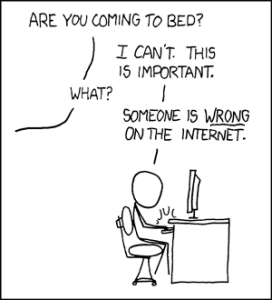

The final step is just to apply common sense: everyone should vote and everyone should be an informed voter, but it would be impossible for all of us to become experts in all of the subject matter we vote about. We can’t practically get PhDs in economics to know how to vote on economic policy and PhDs in climatology to understand climate change and PhDs in foreign relations to know who should be head of the State Department and so on. We have to think about what talents we have, and what we can specialize in, and how we can balance our contributions to the greater good with our personal obligations. For me, given that I’m the kind of nut-job who will spend countless hours and revisions analyzing this kind of question to death and then posting it (complete with xkcd, Harry Potter, and Star Wars references), I guess that means blogging is what I’m suited for.

I hope that’s right, and not just wishful thinking.

More than once I’ve found myself “trapped”: by the idea that I must have an original thought, story, etc to contribute. This point of view is pretty liberating. Thanks for writing it.

Please do post on the myth of evil.

>>In other words, it’s the opposite of what Sirius Black tells Harry Potter: “The world isn’t split into good people and Death Eaters. We’ve all got both light and dark inside us.” <<

He says that, largely in reference to Dolores Umbridge. So guess which side Dolores Umbridge joins in Book Seven?

I had to :P

Trevor – No problem.

Allen – I think I can include the rest of my thoughts on the myth of evil in a post about the arrogance of guilt.

Reece – You’re the worst. :-P

I second Allen’s request.