The Legal Status of Abortion, Revisited

I’ve talked to Terryl Givens[ref]My dad.[/ref] a few times since his article on abortion for Public Square came out. Both of us are disappointed, but not at all surprised, by some of the reactions from fellow Latter-day Saints. I’ll dive into one such response–a post from Sam Brunson at By Common Consent–but only after taking a minute to underscore the difference between an extreme position and a fiercely-held moderate position.

There’s a reason why the first section in Terryl’s piece is an explanation of the current legal status of abortion in the United States. Unlike many other developed nations, where abortion laws were gradually liberalized through democratic means, the democratic process in the United States was short-circuited by the Roe vs. Wade decision (along with Doe vs. Bolton). As Terryl explained, American abortion law since Roe is an extreme outlier: “America is one of very few countries in the world that permit abortion through the 9th month of pregnancy.”

If the spectrum of possible abortion laws runs from “never and under no circumstances” to “always and under any circumstances,” our present situation is very close to the “any circumstances” extreme.

In his rejoinder, Sam rightly points out that Roe is not the last word on the legality of abortion in the United States. Decades of laws and court cases–including return trips to the Supreme Court–have created an extremely complex legal landscape full of technicalities, ambiguities, and contradictions.

But the bottom line to the question of the legal status of abortion in the United States doesn’t require sophisticated legal analysis if we can answer a much simpler set of questions instead. Is it true that there are a large number of late-term abortions in the United States that are elective (i.e. not medically necessary or the result of rape) and legal? That’s the fundamental question, and it’s one Terryl unambiguously asked and answered in his piece (with sources):

Current numbers are between 10,000 and 15,000 late-term abortions performed per year… “[M]ost late-term abortions are elective, done on healthy women with healthy fetuses, and for the same reasons given by women experiencing first-trimester abortions.”

Thus, the key question of the current legal status of abortion in the United States is irrefutably answered. We live in a country where late-term, elective abortions are legal, and we’re one of the only countries in the world with such a radical and extreme position.

This radical position is not at all popular with Americans, as countless polling demonstrates. Here’s Gallup:

It is possible to quibble about whether the current regime is logically identical to “legal under any circumstances.” No matter, the present state of abortion legality is so incredibly extreme that we can afford to be very generous in our analysis. Here are more detailed poll numbers:

American abortion law is more extreme than “legal under most circumstances” but even if we grant that we still find that combined support for the status quo is just 38% while the vast majority would prefer abortion laws stricter than what we have now. And stricter than what we can have, as long as the root of the tree (Roe) is left intact.

How Does A Radical, Unpopular Position Endure?

These opinions have been roughly stable, and so you might reasonably wonder: how is it possible for such an unpopular state of affairs to last for so long? One reason is structural. Because Roe short-circuited the democratic, legislative process the issue is largely out of the hands of (more responsive) state and federal legislatures. Individual states can, and have, passed laws to restrict abortion around the margins, but the kind of simple, “No abortion in the third trimester except for these narrow exceptions” law that they would accurately reflect popular sentiment would inevitably run up against Supreme Court where either the restriction or Roe would have to be ovturned.[ref]The matter is especially complicated when you consider that pro-life activists strategically avoid passing laws like this as long as they know that the Supreme Court would overturn the law and thus even more deeply entrench Roe as precedent.[/ref]

As long as Roe is in place, it’s impossible to limit abortion laws. And yet support for overturning Roe, perversely, is very low. Here’s a recent NBC poll:

Here we have a contradiction. Most Americans want abortion to be limited to only a few, exceptional cases. But this is impossible without overturning Roe. And most Americans don’t want to overturn Roe.

This is the fundamental contradiction that has perpetuated an extremist, unpopular abortion status quo for so long.

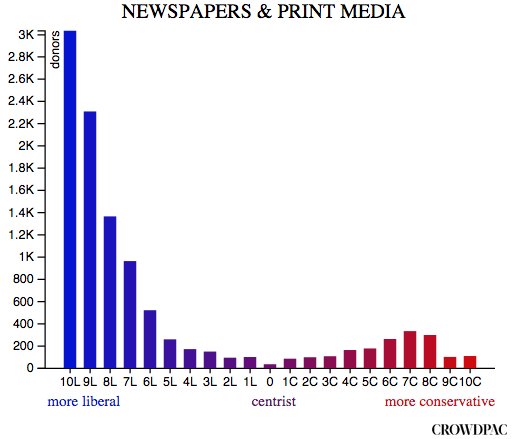

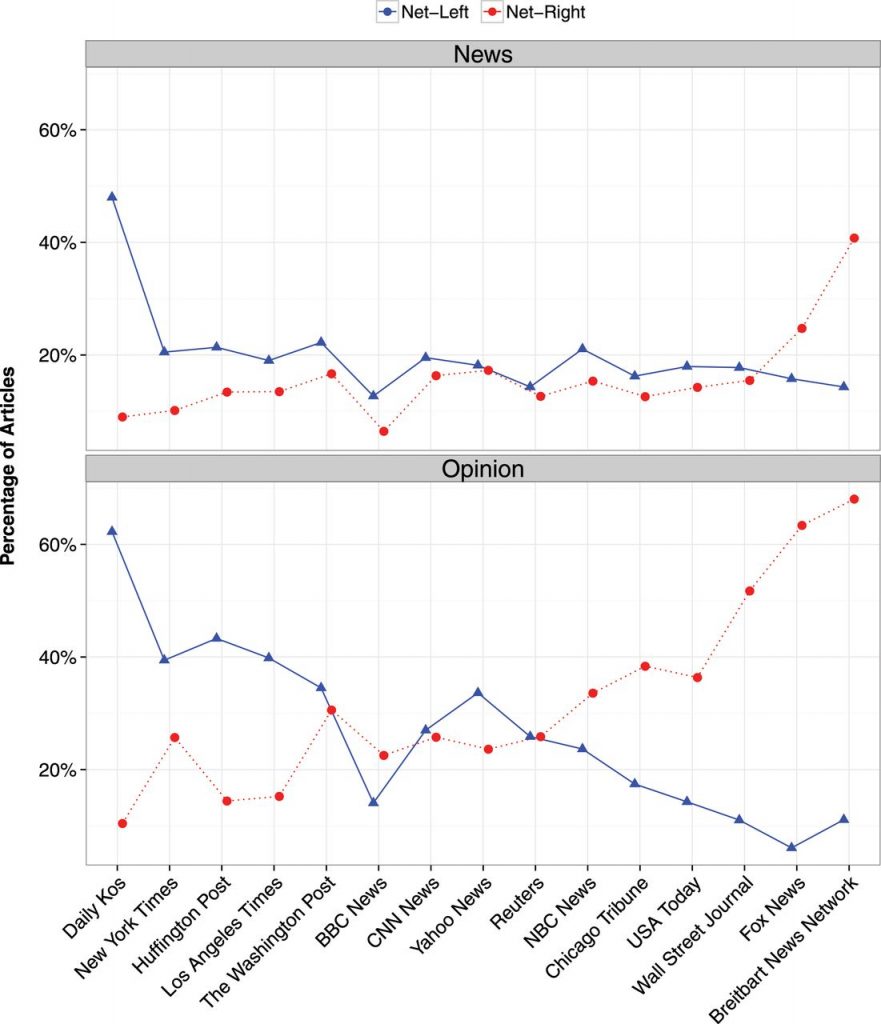

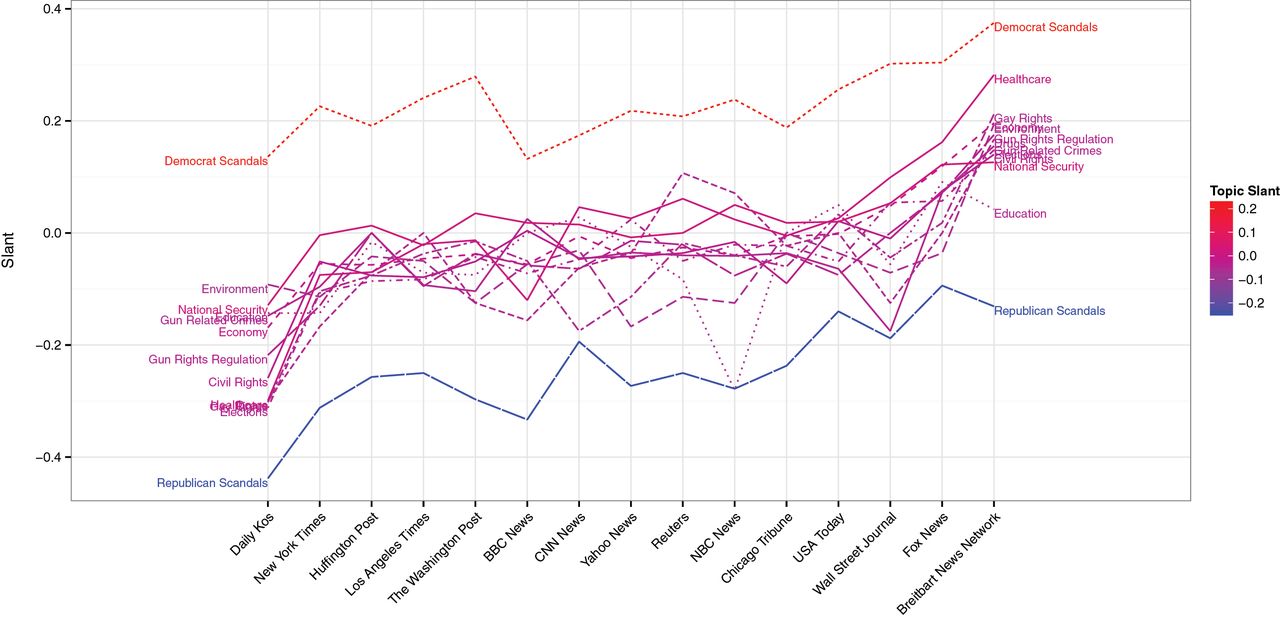

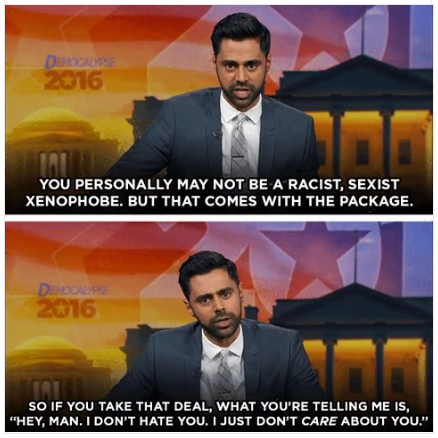

The most straightforward explanation is that Americans support Roe while at the same time supporting the kinds of laws that Roe precludes because they don’t understand Roe. And this is where we get to the heart of the responses to Terryl’s piece (and many, many more like his). The only way to convince Americans to support Roe (even though it goes counter to their actual preferences) is to convince them that Roe is the moderate position and that it is the pro-life side that is radical and extreme.

This involves two crucial myths:

- Elective, late-term abortions do not take place, or only take place for exceptional reasons

- The only alternative to Roe is a blanket ban on all abortions

If Americans understood that elective, late-term abortions are legal and do, in fact, take place in great numbers and if they understood that they only way to change this state of affairs would be to repeal Roe, then support for Roe would plummet. Thus, for those who wish to support the present situation, the agenda is clear: the status quo can only survive as long as the pro-life position is misrepresented as the extreme one.

The Violence of Abortion Protects Abortion

With tragic irony, the indefensibleness of elective abortion makes this task much easier. Abortion is an act of horrific violence against a tiny human being. It is impossible to contemplate this reality and not be traumatized. This is why pro-life activists suffer from burn-out.

It is not just pro-life activists who are traumatized by the violence of abortion, however. The most deeply traumatized are the ones most frequently and closely exposed to the violence of abortion: the abortionists themselves. This is what led Lisa Harris to write “Second Trimester Abortion Provision: Breaking the Silence and Changing the Discourse.” She reports how the advent of second-trimester D&E abortions, which entail the manual dismemberment of the unborn human, led to profound psychological consequences for practitioners when they became common in the late 1970s:

As D&E became increasingly accepted as a superior means of accomplishing second trimester abortion… a small amount of research on provider perspectives on D&E resulted. Kaltreider et al found that some doctors who provided D&E had ‘‘disquieting’’ dreams and strong emotional reactions.

Hern found that D&E was ‘‘qualitatively a different procedure – both medically and emotionally – than early abortion’’. Many of his staff members reported: ‘‘. . .serious emotional reactions that produced physiological symptoms, sleep disturbances (including disturbing dreams), effects on interpersonal relationships and moral anguish.’’

This is the perspective from an abortionist, not some pro-life activist. In fact, Lisa describes performing an abortion herself while she was pregnant:

When I was a little over 18 weeks pregnant with my now pre-school child, I did a second trimester abortion for a patient who was also a little over 18 weeks pregnant. As I reviewed her chart I realised that I was more interested than usual in seeing the fetal parts when I was done, since they would so closely resemble those of my own fetus. I went about doing the procedure as usual, removed the laminaria I had placed earlier and confirmed I had adequate dilation. I used electrical suction to remove the amniotic fluid, picked up my forceps and began to remove the fetus in parts, as I always did. I felt lucky that this one was already in the breech position – it would make grasping small parts (legs and arms) a little easier. With my first pass of the forceps, I grasped an extremity and began to pull it down. I could see a small foot hanging from the teeth of my forceps. With a quick tug, I separated the leg. Precisely at that moment, I felt a kick – a fluttery ‘‘thump, thump’’ in my own uterus. It was one of the first times I felt fetal movement. There was a leg and foot in my forceps, and a ‘‘thump, thump’’ in my abdomen. Instantly, tears were streaming from my eyes – without me – meaning my conscious brain – even being aware of what was going on. I felt as if my response had come entirely from my body, bypassing my usual cognitive processing completely. A message seemed to travel from my hand and my uterus to my tear ducts. It was an overwhelming feeling – a brutally visceral response – heartfelt and unmediated by my training or my feminist pro-choice politics. It was one of the more raw moments in my life. Doing second trimester abortions did not get easier after my pregnancy; in fact, dealing with little infant parts of my born baby only made dealing with dismembered fetal parts sadder.

This is hard to read. Harder to witness. Harder still to perform. That’s Lisa’s point. “There is violence in abortion,” she plainly states, and the point of her paper is that abortionists, like her, need support to psychologically withstand the trauma of perpetrating that violence on tiny human beings again and again and agin.[ref]Although many, like other doctors quoted in the article, simply refuse to do the procedures at all. The real limits of abortion in the United States are not legal, they are that so few people are morally or psychologically capable of tearing apart tiny human beings.[/ref]

Thus, pro-lifers find themselves in a Catch-22 position. If we do nothing, or soft-peddle the true state of affairs, then the pro-choice myths remain uncontested, and misuided public opinion keeps Roe–and elective abortion at any point–safe.

But if we do describe the true nature of abortion then our audienc recoils in shock. Ordinary Americans living their ordinary lives are unprepared for the horror going on all around them, and they are overwhelmed. They desperately want this not to be true. They don’t even want to think about it.

If you tell someone that your neighbor screams at his kids, they will be sad. If you say your neighbor hits his kids, they will urge you to call the police or contact social services. If you say your neighbor is murdering his children one by one and burying them in the backyard, they will probably stop talking to you and maybe even call the cops on you. Sometimes, the worse a problem is the harder it is to get anyone to look at it. That is the case with abortion.

Terryl’s piece was a moderate position strongly argued. He is taking literally the most common position in America: that abortion should be illegal in all but a few circumstances (but that it should be legal in those circumstances). He never stated or even implied that other, ancillary efforts should not be tried (such as birth control).

Abortion is a large, complex issue and there are a lot of ambiguous and aspects to it. But not every single aspect is ambiguous. Some really are clear cut. Such as the fact that it should not be legal to get a late-term abortion for elective reasons. Virtually all Americans assent to this. Why, then, was Terryl’s essay so utterly rejected by some fellow Latter-day Saints?

On Sam Brunson and Abortion

As I mentioned earlier, Sam’s response to Terryl is the first extended one I’ve seen and is pretty representative of the kinds of arguments that are typical in response to pro-life positions. It is a great way to see the factors I’ve described above–the myth-protecting and the violence-denial–put into practice.

Bad Faith[ref]I’ll use the same headings that Sam did, although I don’t intend to respond to every single point.[/ref]

Terryl’s piece includes this line in the first paragraph:

I taught in a private liberal arts college for three decades, where, as is typical in higher education, political views are as diverse as in the North Korean parliament.

This is what is colloquially referred to by most people as: “a joke,” but Sam’s response see it as an opening to impugn Terryl’s motives:

Moreover, bringing up North Korea—an authoritarian dictatorship where dissent can lead to execution—strongly hints that he’s creating a straw opponent, not engaging in good-faith discourse.

Is a humorous line at the expense of North Korea really a violation of “good-faith discourse”? Did he really not recognize that this line was written humorously? I suppose it’s possible, since he seemed to think the BCC audience wouldn’t know North Korea was an authoritarian dictatorship without being told. Also, he is a tax attorney.[ref]This is also a joke.[/ref]

Still, it seems awfully convenient to fail to recognize a joke in such a way that lets you invent some kind of nefarious, implied straw-man argument.

It almost seems like bad faith.

Facts and the Law

This is the section where the first of the two core objectives (defend the myths) is undertaken. Sam characterizes Terryl’s piece as “deeply misleading” and specifically refers to “big [legal] problems,” yet his rejoinder is curiously devoid of substance to validate these claims. For example:

And, in fact, just last week the Sixth Circuit upheld a Kentucky law requiring that abortion clinics have a hospital transfer agreement. So the idea that abortion regulation always fails in the courts is absolutely absurd.

So Terryl says elective abortions are generally legal at any time and the reply is, well those clinics that can provide the abortion at any time for any reason may be required to “have a hospital transfer agreement”. In what way is this in any sense a refutation of the point at hand?

It’s like I said, “buying a light bulb is generally legal at any time for any reason” and you said, “well, yeah, but hardware stores can be required to follow safety regulations.”

… OK?

None of the legal analysis in this section gets to the core fact: are late-term abortions frequently conducted in the United States for elective reasons and are they legal? If that is the case, then no amount of legal analysis can obfuscate the bottom line: yes, abortions are legal for basically any reason at basically any time. There’s room to quibble or qualify, but–so long as that central fact stands–not to fundamentally rebut the assertion.

Sam never even tries.

That’s because, as we covered above, the facts are unimpeachable. Terryl’s source is the Guttmacher Institute, which is the research arm of the nation’s most prolific abortion provider. It’s an objective fact that elective, late-term abortions are legal in the United States as a result of the legal and policy ecosystem descending from the Roe and Doe decisions. Instead of a strong rebuttal of this claim, as we were promised, all we get are glancing, irrelevancies.

Moral Repugnance

Having attempted to defend the myth that later-term abortions are illegal, in this section Sam turns to the next objective: leveraging the violence of abortion to deflect attention from the violence of abortion.[ref]Not a typo.[/ref]

He begins by citing Terryl:

I am not personally opposed to abortion because of religious commitment or precept, because of some abstract principle of “the sanctity of life.” I am personally opposed because my heart and mind, my basic core humanity revolts at the thought of a living sensate human being undergoing vivisection in the womb, being vacuum evacuated, subjected to a salt bath, or, in the “late-term” procedure, having its skull pierced and brain vacuumed out.

Then he presents his own pararaphse: “[Terryl] finds abortion physically disgusting and, at least partly in consequence of that disgust, finds it morally repugnant.”

This is an egregious mischaracterization. I understand that the clause “at least partly” offers a kind of fig leaf so that Sam can say–when pressed–that he’s not actually substituting Terryl’s moral revulsion for a mere gag reflex, but since the rest of the piece exclusively focuses on the straw-man version of Terryl’s argument, that is in fact what he is doing, tenuous preemptive plausible deniability excuses notwithstanding.

To say that the horror of tiny arms and legs being ripped away from a little, living body is the same species of disgust as watching a gall bladder operation is an act of stunning moral deadness.

I understand that urge to look away from abortion. I wish I had never heard of it. And, as we covered above, even a staunch pro-choice feminist and abortionist like Lisa not only admits that abortion is intrinsically violent, but insists that this violence causes a psychological trauma that merits sympathy and support for abortionists who subject themselves to it. She is not the only one, by the way. Another paper, Dangertalk: Voices of abortion providers, includes many additional examples of the way that abortionists frankly discuss abortion in terms of violence, killing, and war when they are away from public view. “It’s like a slaughterhouse–it’s like–line ’em up and kill ’em and then go on to the next one — I feel like that sometimes,” said one. “[Abortion work] feels like being in a war,” said another, “I think about what soldiers feel like when they kill.”

Given this, Sam’s substitution from moral revulsion at an act of violence to physical revulsion at blood and guts is unmasked for what it truly is: a deflection. Abortion is very, very hard to look at. And that’s convenient for pro-choicers, because they don’t want you to see it.

The reset of this section is largely a continuation of the deflection.

- “Why no support for, for example, free access to high-quality contraception?”

- “[Y]ou know what I consider disgusting? Unnecessary maternal death.”

- “You know what else I consider morally repugnant? Racial inequality.”

I do not wish to sound remotely dismissive of these entirely valid statements. Each of them is legitimate and worthy of consideration. Nothing in Terryl’s piece or in my position contradicts any of them. Let us have high-quality contraception, high-quality maternal care, and a commitment to ending racial inequality.

But we do not have to stint on our dedication to any of those policies or causes to note that–separate and independent from these considerations–elective, late-term abortions are horrifically violent.

These are serious considerations, and they deserve to be treated as more than mere padding to create psychological distance from the trauma of abortion. Just as women, too, deserve a better solution for the hardship of an unplanned pregnancy than abortion.

To the Latter-day Saints?

Sam writes that, “Although he claims to be making a Latter-day Saint defense of the unborn, his argumentation is almost entirely devoid of Latter-day Saint content.” Here, at least, he is basically correct. Not that he’s made some insightful observation, of course. He’s just repeating Terryl’s words from the prior quote: “I am not personally opposed to abortion because of religious commitment or precept.”

In this section, which I find the least objectionable, Sam tries to carve out space for Latter-day Saints to be personally pro-life and publicly pro-choice, including a few half-hearted references to General Authorities and Latter-day Saint theology. I say “half-hearted” because I suspect Sam knows as well as I do that President Nelson and President Oaks, to name just two, have spoken forcefully and clearly in direct contradiction to Latter-day Saint attempts to find some kind of wiggle room around “free agency” or to view the lives of unborn human beings as anything less than equal with the lives of born human beings.

No one should countenance the legality of elective abortion at all, but Latter-day Saints especially so.

The Moral Imagination

In the final section, Sam circles back to the myth-defending. The first myth to defend is that elective, late-term abortions do not take place in the United States, which is just a detailed way of saying that the pro-choice side seeks to conceal the radicalism of our current laws.

The second myth to defend, which occupies this section, is the myth that any alternative to our current laws must be the truly extreme option.

So in this section we encounter new straw-men such as: “it’s not worth pursuing other routes to reduce the prevalence of abortion.” Terryl never says that, nothing in his article logically entails that, and I know he does not believe that. One can say, for example, “theft ought to be illegal” and also support anti-poverty measures, after-school programs, and free alarm systems to reduce theft. Much the same is true here: one can support banning elective abortion and support a whole range of additional policies to lower the demand for abortion.

Similarly, he writes that “I find abortion troubling as, I believe, most people do. But I also find a world without legal abortion troubling.” That sounds modest and reasonable enough, but it’s another straw-man. The Church, as he noted in the previous section, “has no issue with abortion” in exceptional cases. Neither does Terryl. So the issue is not “a world without legal abortion” because no one has argued for that position. The issue is “a world without legal elective abortion”. Omitting that word is another great example of a straw-man argument.

By making it appear as though Terryl wishes to ban all abortions and refuses to consider any alternative policies to reduce abortions, Sam creates the impression that Terryl is the one with the radical proposal. Except, as I’ve noted, neither of those assertions is grounded in anything other than an attempt to preserve vital myths.

Wrap-up

I echo what Terryl originally said: “I do not see reproductive rights and female autonomy as simple black and white issues.” Abortion as a whole is very, very complicated issue legally, scientifically, and morally. There is ample room for nuanced discussion, policy compromise, and common ground.

But for us to have that kind of a conversation, we have to start with honesty. That means dispensing with the myths that American abortion law is moderate or that abortion is anything other than deeply and intrinsically violent. And it means allowing pro-lifers to speak for themselves, rather than substituting extremist views for their actual positions.

Because abortion is so horrific, pro-lifers face a tough, up-hill slog. But because it is so horrific, we can’t abandon the calling. We will continue to seek out the best ways to boldly stand for the innocent who have no voice, to balance the competing and essential welfare needs of women with the right to life of unborn children, and to advance our modest positions as effectively as possible.