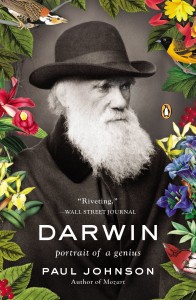

Paul Johnson, Darwin: Portrait of a Genius (New York: Viking, 2012).

Paul Johnson, Darwin: Portrait of a Genius (New York: Viking, 2012).

Popular historian Paul Johnson’s slim biography/analysis of Charles Darwin and his theory is a surprisingly satisfying read in light of its relatively short length (clocking in under 200 pages). While likely of passing interest to scholars and those already well-acquainted with Darwin’s life, Johnson’s brief, but informative overview will be of value to the general reader. Johnson does a fine job of accurately describing what Darwin actually wrote and distinguishing it from those things that are often placed in his mouth. While he engages in a bit of pop psychology to support some of his sweeping statements, Johnson is nonetheless fresh and thoughtful in his writing. Most important, Johnson is able to paint a vivid picture of the broader context from which Darwin’s ideas emerged. This is consistent with one of Johnson’s major themes: ideas matter and often take on a life of their own. Thus, Darwin’s Malthusian interpretation of the evidence viewed evolutionary life as a vicious, violent struggle for existence. This outlook in turn aided other ideologies and movements that sought to use Darwinism to bolster their own worldviews, including eugenics, Nazism, and Communism. It is this latter portion on which some negative reviewers have focused their attention, despite the fact that it consists of only one chapter (Ch. 7 “Evils of Social Darwinism”). Mark Stern at Slate writes that Johnson’s “discussion of the world’s reaction to The Origin of Species” is “admittedly engaging.” Furthermore, he sees “Johnson’s overview of Darwin’s theory of evolution” as “clear, rich, and accurate.” Yet, the majority of his review is dedicated to explaining that there is “intellectual harm, historical harm, and moral harm” in linking Darwin to any of the 20th-century atrocities. The review’s subtitle describes the book as “the latest effort to smear evolution by natural selection.” Of course, Stern explains that such a book obviously comes from “a conservative, family-values-promoting British intellectual” who “has spoken out against divorce, liberation theology, unions, atheism, the Enlightenment, and even the Beatles.” Another (albeit shorter) review in the New Scientist bluntly states that Johnson’s book is nothing more than “a vendetta, an agenda-driven hatchet-job.” There is some truth to these criticisms. Johnson does emphasize that Darwin was a “poor anthropologist” who “did not bring to his observation of humans the same care, objectivity, acute notation, and calmness he always showed when studying birds and sea creatures, insects, plants, and animals” (pg. 29). For example, Johnson points to Darwin’s opinions of the Fuegan “savages” during his voyage on the Beagle as evidence of his lacking in anthropology. While an important factor, I’m reminded of another scholar’s take on the matter:

When incautious scholars or blinkered fundamentalists accuse Darwin or [German Darwinist Ernst] Haeckel of racism, they simply reveal to an astonished world that these thinkers lived in the nineteenth century.[ref]Robert J. Richards, “Myth 19: That Darwin and Haeckel Were Complicit in Nazi Biology,” Galileo Goes to Jail: And Other Myths About Science and Religion, ed. Ronald L. Numbers (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2009), 174.[/ref]