There was an initial wave of angry condemnation when The Triple Package was first released, and my problem with that reactionary wave was just that: It was reactionary. It’s been over a month since those first-pass criticisms were unleashed, and over at Slate Daria Roithmayr has had time to formulate a more nuanced and sophisticated response. Or, as turns out to be the case, not. Instead, her response shows the twin perils of (A) putting politics ahead of reality and (B) espousing historical theories without consulting Wikipedia first[ref]I’m not saying Wikipedia is the final word on research, but if you don’t at least start there…[/ref].

According to Roithmayr, the real reason that different cultural groups perform differently is that they start out with unequal resources. Otherwise: we are all exactly the same. The problem is that Roithmayr pretends it’s a conclusion of her research when quite obviously it is pure political dogma. She explains the success of each of the seven cultural groups identified by Chua in their turn. I’m not a historian, so I’m not qualified to analyze all of them, but in the case of her hypothesis about what makes Mormons successful, her explanation is so bad that you don’t have to be. Even the most superficial familiarity with our history[ref]Again: Wikipedia[/ref] shows that she has no idea what she’s writing about. Consider:

It’s not just that Mormons have developed a “pioneer spirit” or that they believe that they can receive divine revelations, as Triple Package would have us believe. It’s more that the first Mormons started with enough money to buy a great deal of land in Missouri and Illinois. They then migrated to Utah, where Brigham Young and his followers essentially stole land from the Shoshone and Ute tribes, refusing to pay what the tribes demanded, and petitioning for the government to remove them. Beyond thousands of acres of free land, early political control over Utah was helpful.

So here’s the true story of Mormonism: a bunch of really wealthy families just decided to buy a bunch of land in New York, Ohio, Missouri, Illinois, and so forth. Why did they keep moving around and buying new land? Oh, you know, just because. They were fickle like that. Then they thought it would be fun to move to Utah because, you know, the land by the Great Salt Lake is legendary for being so fertile. That’s what everyone says when they drive through Utah, right?

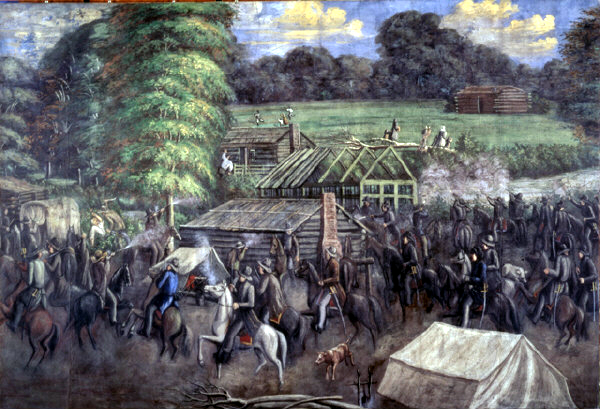

In case you can’t detect all the sarcasm, the reality is that the Mormons were poor and marginalized from the start and that they moved from one state to the other at the point of a gun, suffering murders, rapes, and theft along the way. When they managed to build the city of Nauvoo up to one of the largest American cities at the time, well, that was about the time Joseph Smith was murdered and they were surrounded by thousands of armed men with, you know, cannons and then forced out of their homes without compensation in the middle of winter.[ref]They were able to walk across the Mississippi on their way out.[/ref] The land they stole in Utah was only marginally fit for agriculture and the reason they were there in the first place was simply to get away from constant oppression, but that ended up not working so well when the United States sent the largest federal expeditionary force of its history (to that point) to subjugate those wacky religious nuts, resulting in the low-grade Utah War of 1857[ref]Not to be confused with the Mormon War of 1838 in Missouri or the Mormon War of 1844-1848 in Illinois. In case it isn’t clear: Mormons lost those wars. Or, as Roithmayr puts, it, we “migrated”.[/ref]

Since Roithmayr says “For many groups, like Cubans and Mormons, the early wave was a select group endowed with some significant material or nonmaterial resources—wealth, education, or maybe a government resettlement package,” and since Mormons were by and large quite poor[ref]Definitely after all the pillaging and running for their lives if not before.[/ref] the only reasonable conclusion is that she can’t tell the difference between a resettlement package and an armed invasion.

She mentions Mormons one more time, writing:

The most recent (newly converted) Mormons hail from Africa and Latin America, and many of them have migrated to the U.S. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has also begun outreach to U.S.-born blacks (African-Americans have only been allowed in the Mormon church priesthood since 1978). Black Mormon trajectories look nothing like the white Mormons at the center of The Triple Package’s argument.

Keen observers might point out the obvious fact that “recent” converts are probably not the best indication of the long-run effects of a culture.

Again: I’m still skeptical of Chua’s points. I haven’t read the book and I don’t subscribe to the thesis. I’m also not nearly as familiar with the history of the other cultures described. I do know that in general there’s a serious selection problem when you’re comparing immigrants (often those with the wealth and education to be mobile) with their home population (sometimes slanted towards those unable to get away). I think Roithmayr could probably have made a serious, convincing counter-argument if she’d been willing to put history ahead of ideological wish-fulfillment. As it stands, she’s making the case against Triple Package look worse, and she’s not doing much for the either the credibility of either Slate or the discipline of critical race theory.

It really was a ridiculous assertion. Nate and Kaimi are taking her to task on Facebook, where her response is “obviously I can’t really explain Mormon history in a 1600 word article.”

If you’ve got a link, Ben, I’d enjoy taking a look. I’ve seen some commentary on Nate’s FB wall, but not the discussion with Kaimi and and Daria as well. (That excuse is ultimate weak-sauce anyway.)

Nevermind, I found it. The link is to Daria’s personal Facebook page, but the post is viewable to the public.

Kaimi and Nate are both being civil to the point of silliness, and I’m not going to go all bull in a china shop, but really “I only had 1,600 words” is no excuse when the 30 words you do use are the opposite of reality. The Church didn’t start out with any initial endowment of wealth whatsoever. Her assertion “but they were landowners” is factually false (they bought the land on credit, as Nate pointed out, or were squatting and hoping for pre-emption rights) and on top of the lack of any positive wealth, she completely and totally ignores the rather large cost of the persecution they faced.

Nate’s right when he says:

But I think the language is too nuanced for most people to really grasp the magnitude of the absurdity of Daria’s argument.

Did your headline make me laugh out loud?

You bet it did.

Credit where credit is due, I lifted that line from this scene in Firefly. :-)

Mormon cultural success in America I think has more to do with some of the things Miles Kimball lays out in one of my first posts: https://difficultrun.nathanielgivens.com/2013/08/12/conservative-mormon-america-vs-white-conservative-america/

Hi all:

Appreciate the discussion and the opportunity to engage on the question. Hope you don’t mind my weighing in!

Here’s a more completely reply than what you were reading on my FB page. According to Flanders, in Nauvoo: Kingdom on the Mississippi, there was a fair amount of purchasing going on–purchasing various towns on the Illinois and Iowa sides respectively. To be sure, some of the purchasing was done on credit, but as Flanders’ book reflects, much of it was cash as well. I was careful to say in the review that members had enough money to purchase land, and Flanders’ book supports that. My comment about the 1600 word limit is meant to reflect that the complexities of what land was purchased on credit and what on cash was beyond the detail one could offer in a short review, as opposed to a book length treatment. I also noted in the discussion that by the book’s own statistics, Mormons are slightly less likely to graduate college and not any more likely to earn over $100,000. I point this out only to explain why early conditions do not have to explain that much in the way of group success.

I will be the first to admit that I am not an expert in Mormon history, but I count discussions like yours here on this page as a success–you are debating the question by engaging with me and each other on a fuller discussion of group history and of subsequent cohorts. To my mind, this is a far better conversation than one that relies on overly simplistic notions of culture that completely ignore or heavily discount the history. Let me restate as I do in the review that culture plays a role, just not a role that one can understand without looking at the specific group histories, and material conditions that are part of that history.

Again, I appreciate the conversation as one worth having, even if we disagree on the conclusions we draw. Don’t know if that’s enough to persuade you to give Slate some credit, but it was worth a shot. ;-)

Daria-

Of course I don’t mind having you weigh in yourself! I appreciate your willingness to do so, even if I ultimately do not find your reasoning persuasive.

The first problem is that the micro-issue of whether or not Mormons were able to purchase any land outright largely misses the point. Even if some Mormons were able to purchase some land, this in no way supports your larger argument: which is that Mormons were comparatively well-off relative to their contemporaries. Obviously, they were not.

The second problem comes from this curious line of reasoning:

Your initial argument said that cultures that got lucky historically subsequently do quite well. But you now seem to be arguing that Mormons really did have an advantageous start, but that this ended up having no real benefit a couple of centuries down the road. That’s the logical contradiction of your initial position.

Wouldn’t it be simpler–and more consistent with your political objectives–to simply state that Mormons didn’t have an initial endowment of wealth and that therefore stories of their contemporary success are overblown?

It’s worth noting that this “privileged” culture was seen as racially “Other” by outsiders (frankly, I think this is somewhat true today). Once the Mormons went West and stories of polygamy reached the American public, the Mormons (who were largely Yankee or Northern European converts) were seen as a foreign race. The “unnatural” practice of polygamy was seen as a kind of “race treason,” giving rise to a new distorted race of sexually deviant creatures. Mormons faced legal opposition that was seen as justifiable based on their racial inferiority.

See Nathan B. Oman, “Natural Law and the Rhetoric of Empire: Reynolds v. United States, Polygamy, and Imperialism,” Washington University Law Review 88:3 (2011).

But the view that Mormons were racially “Other” emerged even before Utah. In fact, it was a motivating factor behind the extermination order in Missouri due to major cultural differences and the actual and perceived liking Mormons had for blacks and American Indians (not to mention the Mormons’ claim to be God’s chosen people: literally a new Israel).

See T. Ward Frampton, “‘Some Savage Tribe’: Race, Legal Violence, and the Mormon War of 1838,” Journal of Mormon History 40:1 (2014).

Considering that discrimination of this kind tends to be an argument as to why many groups *don’t* do very well, I just find it odd that that early Mormons are being described in the piece as a rich, privileged group.

Terryl Givens has written at book length on this theme of 19th-century Americans seeing Mormons as socially “Other”: http://www.amazon.com/The-Viper-Hearth-Construction-Religion/dp/0195101839/ref=sr_1_2?ie=UTF8&qid=1392592563&sr=8-2&keywords=viper+on+the+hearth

For those interested, Nate Oman (who had been leveling some criticisms on Facebook as was linked earlier in the comments) has just posted a longer critique at PrawfsBlawg. He goes into greater detail about why the problems with the original Slate piece can’t be reconciled by questions of word-count or nuance. It’s just fundamentally wrong to assert that anything can be explained by the fact of Mormons’ initial wealth because they didn’t have any initial wealth (relative to other folks). As Nate says:

I recommend the whole thing.