Metallica frontman James Hetfield sat down in Guitar Center to give a fairly intimate interview on his musical beginnings and experience with Metallica. What makes it even better is the brief riffing in between. Check it out below.

Month: February 2014

Giving Back to Society

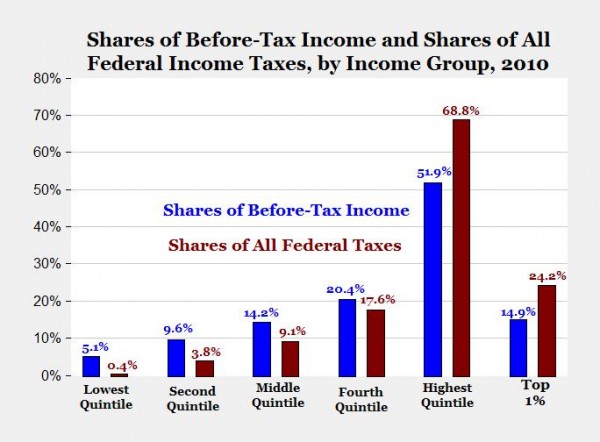

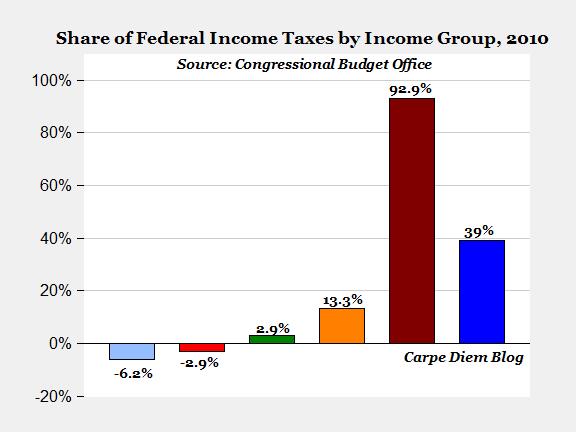

Drawing on data from the Congressional Budget Office, economist Mark Perry provides the following two charts:

“As the data show in the top chart,” writes Perry,

the shares of pre-tax income for the four lower income groups was greater than their shares of federal taxes paid in 2010. In contrast, the highest quintile earned about half (51.9%) of all income in 2010 but paid more than two-third (68.8%) of all federal taxes collected. The top 1% earned 14.9% of pre-tax income in 2010 but paid 24.2% of all federal taxes collected…The federal tax system is highly progressive (higher income households shoulder an increasingly greater tax burden), especially for federal income taxes, as the bottom chart shows. The top income quintile paid almost all federal income taxes in 2010 (94.1%), and the top 1% paid almost 39% of all income taxes. In contrast, the bottom two income quintiles actually had negative shares of income taxes in 2010 and were in fact “net tax receivers” because their refundable tax credits exceeded the income tax otherwise owed.

Not only do the top earners pay the highest amount of taxes, but it tends to be their innovations that benefit society as a whole. Yale economist William Nordhaus’ 2004 paper “Schumpeterian Profits in the American Economy: Theory and Measurement” found that innovators only capture 2.2% of the total present value of social returns. As GMU economist Don Boudreaux pointed out, “The smallness of this figure is astounding. If it is anywhere close to being an accurate estimate, the implication is that “society” pays a paltry $2.20 for every $100 worth of welfare it enjoys from innovating activities.”

The rich may be evil and all that, but they sure do pay for it.

Playing The Blame Game

There’s been some outrage in the video game community lately about a recent mobile game, Dungeon Keeper, released by EA, a game which, according to said community, embodies the worst and most cynical of what the mobile game industry has to offer. Why the outrage at this particular game? Well…

- It’s an EA game. EA was once the pride of the video game industry. Back in the late ’80s to late ’90s, EA released classics year after year like they couldn’t get rid of them fast enough. In true “you either die a hero…” fashion, however, their phenomenal successes led to interest by the world at large and EA became a corporate behemoth more interested in vacuuming up talent wherever it could find it and putting it to work 80 hours a week pumping out half-finished yearly installments of the most lucrative properties than creating the labors of love that characterized their earlier days. Today, EA, together with Activision, represent to many gamers everything that is unsustainable and wrong with the modern video game industry.

- It’s a “remake” of a classic title. The original Dungeon Keeper (1997) holds a special place in the hearts of many gamers and was a product of the EA golden age.

- It’s a “broken-by-design” free-to-play (F2P) game. These types of games are only “free” in the loosest sense of the word. While there is no charge to download and begin playing the game, your progress in the game is punctuated by hours-long wait times to perform even simple actions, forcing players to wait upwards of 24 hours before an action completes and being allowed to queue up another. The only way to actually play the game continuously is to pay real money for resources which eliminate or reduce the timer mechanic. The exchange rate of this resource is such that to have an experience roughly “comparable” (see #4) to the original Dungeon Keeper game, a player would have to pay tens or even hundreds of dollars.

- It is not anything like the original game. Even putting aside the F2P mechanics, very little of the game experience actually resembles the original. If the art assets and the title were changed, it is debatable that anybody would conclude that this new game were even so much as an homage to the first Dungeon Keeper.

Predictably, gamers are upset about the game and its business model. It cheaply cashes in on a classic title while engaging in psychological warfare with players in an attempt to separate them from their money. And what to make of the overwhelmingly positive customer reviews for the game on the App Store? Many are convinced that this means the future generation of players will accept this type of “gameplay” as standard and, as such, it will become increasingly widespread. Gamers are calling EA out, vicious in their criticism of the title and its predatory business model, but is that where the problem is?

I wonder what legitimate justification we have in blaming EA for creating and releasing such a game if people are willing to play it and pay money for it. Obviously, if people weren’t paying for these types of games then there wouldn’t be much reason to continue releasing them. Does EA have any responsibility to adhere to some standard of integrity with regards to the games it releases? In two words: absolutely not. Why should they? The responsibility for the enforcement of “integrity” lays with the customer. That’s the way the it works. It’s a voluntary market.

In my mind, it’s every bit as insidious as EA’s repulsive business practices to imagine companies should cleave to some arbitrary standard of conduct with regard to the type and quality of their products. So long as they are not doing anything illegal, the notion that they’re doing anything objectively wrong or evil is misguided. EA is not your friend, nor should you expect them to be. They’re not on your “side.” They want your money and they’ll happily take it if you’ll give it. The idea of the benevolent business, of companies and individuals laboring for the love and passion of their work with money as simply a byproduct is often symptomatic of a very dangerous and pervasive mindset that seeks to dictate remuneration rather than allow it to emerge a result of free exchange. We can hope for (what we consider) better, yes, but we should not expect it and we should never enforce it.

Companies like EA by and large reflect the tastes of the market they serve, therefore the market shoulders the blame. Dungeon Keeper may be cynical, it may be exploitative, it may even barely qualify as a game at all, but it also represents jobs, and it represents what we, as a game-playing public, have told them we’re prepared to pay for. This is not a defense of the new Dungeon Keeper, of EA or of such so-called “games,” it’s simply an opportunity to take responsibility.

After all, if a seal bathes himself in blood and swims lazily across the nose of a shark, whose fault is it if he gets bitten?

The Greatest Period in American History

Being pregnant 100 years ago was almost as dangerous as having breast cancer is today.

So states an article over at The Motley Fool. The author goes on to list 50 reasons why we are living in the greatest period in American history. Below were some of my favorites:

- U.S. life expectancy at birth was 39 years in 1800, 49 years in 1900, 68 years in 1950, and 79 years today. The average newborn today can expect to live an entire generation longer than his great-grandparents could.

- A flu pandemic in 1918 infected 500 million people and killed as many as 100 million. In his book The Great Influenza, John Barry describes the illness as if “someone were hammering a wedge into your skull just behind the eyes, and body aches so intense they felt like bones breaking.” Today, you can go to Safeway and get a flu shot. It costs 15 bucks. You might feel a little poke.

- The average American now retires at age 62. One hundred years ago, the average American died at age 51. Enjoy your golden years — your ancestors didn’t get any of them.

- In his 1770s book The Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith wrote: “It is not uncommon in the highlands of Scotland for a mother who has borne 20 children not to have 2 alive.” Infant mortality in America has dropped from 58 per 1,000 births in 1933 to less than six per 1,000 births in 2010, according to the World Health Organization. There are about 11,000 births in America each day, so this improvement means more than 200,000 infants now survive each year who wouldn’t have 80 years ago. That’s like adding a city the size of Boise, Idaho, every year.

- Two percent of American homes had electricity in 1900. J.P Morgan (the man) was one of the first to install electricity in his home, and it required a private power plant on his property. Even by 1950, close to 30% of American homes didn’t have electricity. It wasn’t until the 1970s that virtually all homes were powered. Adjusted for wage growth, electricity cost more than 10 times as much in 1900 as it does today, according to professor Julian Simon.

- According to the Federal Reserve, the number of lifetime years spent in leisure — retirement plus time off during your working years — rose from 11 years in 1870 to 35 years by 1990. Given the rise in life expectancy, it’s probably close to 40 years today. Which is amazing: The average American spends nearly half his life in leisure. If you had told this to the average American 100 years ago, that person would have considered you wealthy beyond imagination.

- You need an annual income of $34,000 a year to be in the richest 1% of the world, according to World Bank economist Branko Milanovic’s 2010 book The Haves and the Have-Nots. To be in the top half of the globe you need to earn just $1,225 a year. For the top 20%, it’s $5,000 per year. Enter the top 10% with $12,000 a year. To be included in the top 0.1% requires an annual income of $70,000. America’s poorest are some of the world’s richest.

- In 1900, 44% of all American jobs were in farming. Today, around 2% are. We’ve become so efficient at the basic need of feeding ourselves that nearly half the population can now work on other stuff.

And much, much more. Check it out.

Startup Cities

Over the last year or so, I’ve become somewhat fascinated with cities and urban studies. The video below, featuring Chapman University law professor Tom W. Bell, is one reason why. In his lecture, Bell discusses ZEDEs: zones of economic development. These “startup cities” could potentially bring on new forms of governance. This is likely a good introduction to his forthcoming article in Social Philosophy & Policy titled “What Can Corporations Teach Governments About Democratic Equality?” The abstract reads,

Democracies place great faith in the principle of one-person/one-vote. Business corporations and other private entities, in contrast, typically operate under the one- share/one-vote rule, allocating control in proportion to ownership. Why the difference? In times past, we might have cited the differing ends of public and private institutions. Whereas public democracies aim at promoting the general welfare of an entire political community, private entities aim at more specific goals, such as generating profits or managing a cooperative residence. As business entities have grown in size and in the range of services they provide, however, the distinction between public and private governance has grown blurry. Soon, entire “startup cities” may join residential cooperatives and homeowners associations in drawing their governing principles from private sources. How can private communities affirm the principles of democratic equality? By affording full protection to all rights holders, individuals and owners alike. The one-person/one-vote approach popular in political contexts works best at protecting the individual personal rights—freedoms of conscience, speech, and innumerable others—to which each of us has an equal claim. Corporate law’s one-share/one-vote rule works best at protecting the property rights of those who invest in a commonly owned community. This paper explains why a polity should offer both corrective and constructive democracy. Residents exercise corrective democracy in defense of their individual rights by submitting officials and laws to popular veto. Shareholders exercise constructive democracy in defense of their investments, choosing directors and managing polity governance. The result: a double democracy that combines the best features of public and private governance to give equal treatment to both the personal rights of individual residents and the property rights of shareholder owners. Respect for democratic equality demands nothing less.

I’m excited to see how these ideas develop further.

The Babylonian Ark

The Biblical Archaeology Review has a write-up on a newly-translated Old Babylonian (1900-1700 B.C.E.) tablet. The tablet’s translator Irving Finkel sees the tablet as “an ark builder’s how-to guide.” But what is really interesting is the way the ark is described in the tablet:

The Biblical Archaeology Review has a write-up on a newly-translated Old Babylonian (1900-1700 B.C.E.) tablet. The tablet’s translator Irving Finkel sees the tablet as “an ark builder’s how-to guide.” But what is really interesting is the way the ark is described in the tablet:

The most remarkable feature provided by the Ark Tablet is that the lifeboat built by Atra-hasıs— the Noah-like hero who receives his instructions from the god Enki—was definitely, unambiguously round. “Draw out the boat that you will make,” he is instructed, “on a circular plan.”

Check it out.