I have decided to use Nathaniel’s Top 10 post as a reason to do my own. This was a fairly difficult list to make, but it was likely easier than a list of “favorite” or “best” books. What makes this list different from those is that I don’t have to think the books are any good. They could in principle be awful. What matters is the impact they had on me. However, my life has been influenced by many articles and essays, which technically don’t count. For example, Nobel economist F.A. Hayek’s 1945 article “The Use of Knowledge in Society” was far more influential than, say, his famous book The Road to Serfdom. Hamlet continues to enthrall me and was the main reason I came to love Shakespeare. It ignites my emotions and a need to reflect in a way few works do. I didn’t include it mainly because it is a play, but also because my initial reading of it was intertwined with a viewing of Kenneth Branagh’s film version (which I love). The FARMS Review (now the Mormon Studies Review) was a highly influential journal for me and my main introduction to biblical and Mormon scholarship. My familiarity with academic journals was largely because of it. But obviously, journals don’t count. David Foster Wallace’s commencement speech/essay “This Is Water” has influenced the way I view the mundane in everyday life. This in turn inspired numerous blog posts, a conference paper, and a new direction of research for me. But it is an essay, not a book. Of course, there are my many kind and intelligent friends that have helped shape my views through discussions, recommendations, blog posts, theses and dissertations, etc. As you can see, plenty of influential pieces and people are being left out, some of which are pretty big.

Now that that has been clarified, let’s proceed with the list (in the order I read them):

1. The LDS Standard Works

Being a devout Latter-day Saint (Mormon), it shouldn’t be any surprise that our scriptural canon shows up on the list. One could say that the Bible, Book of Mormon, Doctrine & Covenants, and Pearl of Great Price are all separate books (and they’d be right), but as you can see in the pic, the four are often published together in a “quad.” These “standard works” are essentially the Mormon canon. Understanding the historical, cultural, textual, and theological meaning of these texts take up a considerable amount of my time and thinking. These are the foundational texts for the paradigm by which I make sense of life. And it was the desire to learn everything I could about these texts and their meaning(s) that eventually spilled over into various fields.

Being a devout Latter-day Saint (Mormon), it shouldn’t be any surprise that our scriptural canon shows up on the list. One could say that the Bible, Book of Mormon, Doctrine & Covenants, and Pearl of Great Price are all separate books (and they’d be right), but as you can see in the pic, the four are often published together in a “quad.” These “standard works” are essentially the Mormon canon. Understanding the historical, cultural, textual, and theological meaning of these texts take up a considerable amount of my time and thinking. These are the foundational texts for the paradigm by which I make sense of life. And it was the desire to learn everything I could about these texts and their meaning(s) that eventually spilled over into various fields.

2. Bill Watterson, The Calvin and Hobbes Tenth Anniversary Book (1995)

I often say that Calvin and Hobbes was my first introduction to philosophy. And I mean that quite seriously. I used to remove the “funnies” every Sunday morning from the paper in order to read the latest strip from Watterson. I cut out strips centered around Spaceman Spiff and kept them in a folder (I was a big Star Wars fan, therefore, anything with space was cool). Calvin & Hobbes strips are scattered with nostalgia, wisdom, practicality, and imagination. I now own five C&H volumes. The 10th anniversary book was my first and features an introduction by Watterson, which discusses the transition of comics, his influences, the constraints of Sunday strip formats, an explanation of the recurring characters, etc. But the best part is his commentary on the various strips, no matter how brief. For example, the strip where Calvin breaks his dad’s binoculars features this insert from Watterson: “I think we’ve all gone through something like this story. You die a thousand deaths before you even get in trouble.” Nice to know someone else gets the small things in life.

3. Truman G. Madsen, Joseph Smith the Prophet (1989)

I’m slightly cheating here. At the very beginning of my mission, my trainer (i.e. first missionary companion) owned Madsen’s 1978 audio lectures titled Joseph Smith the Prophet. I didn’t come into contact with the book version until I was well off my mission. But given the fact that the book is basically a word-for-word reprint of the lectures, I included it. I cannot stress enough the impact of these lectures. We listened to them in the car during our travels (when we had a car). I would lay awake late at night listening to them with my headphones. I included them as part of my personal morning studies. This was the first time that Joseph Smith, the founder of my religion, became real to me. While still a positive, faith-promoting rendition, it was the first time he was fleshed out as a living human being. More than that, it was the first time that I can remember any historical figure being fleshed out in my mind. Up to that point, history was an abstraction to me. But these lectures made me want to dive into the details and nuances of history (and eventually everything else). While scholarship over the last few decades has surpassed this, it was still monumental for me. In essence, this was the beginning of my intellectual journey.

I’m slightly cheating here. At the very beginning of my mission, my trainer (i.e. first missionary companion) owned Madsen’s 1978 audio lectures titled Joseph Smith the Prophet. I didn’t come into contact with the book version until I was well off my mission. But given the fact that the book is basically a word-for-word reprint of the lectures, I included it. I cannot stress enough the impact of these lectures. We listened to them in the car during our travels (when we had a car). I would lay awake late at night listening to them with my headphones. I included them as part of my personal morning studies. This was the first time that Joseph Smith, the founder of my religion, became real to me. While still a positive, faith-promoting rendition, it was the first time he was fleshed out as a living human being. More than that, it was the first time that I can remember any historical figure being fleshed out in my mind. Up to that point, history was an abstraction to me. But these lectures made me want to dive into the details and nuances of history (and eventually everything else). While scholarship over the last few decades has surpassed this, it was still monumental for me. In essence, this was the beginning of my intellectual journey.

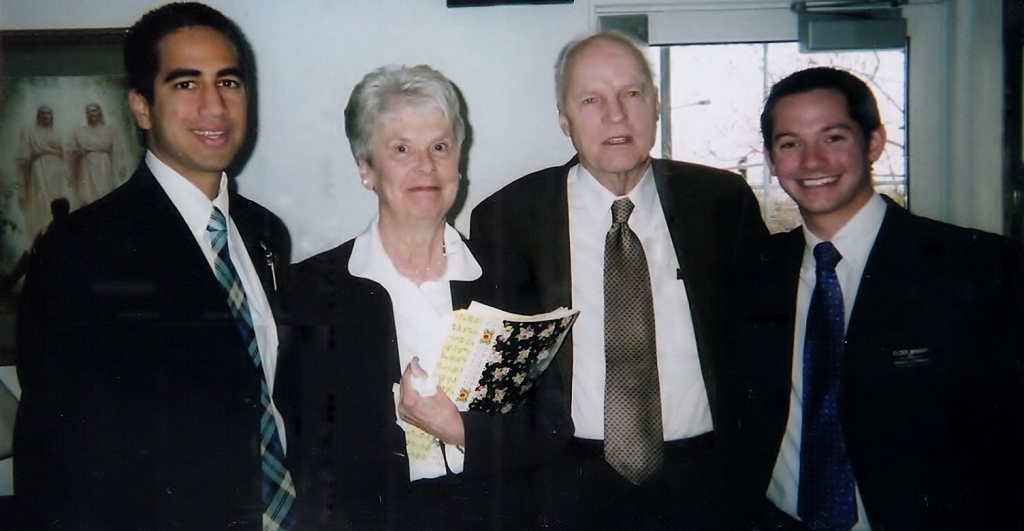

I was lucky enough to meet Truman and Ann Madsen at a women’s conference in Las Vegas on my mission. We four missionaries (me, my companion, and another missionary companionship) were virtually the only males in attendance. I was saddened when Truman passed away a couple years later. It made me all the more grateful that I had been able to thank him personally for the impact his work had on me.

4. Gerald L. Schroeder, The Science of God: Convergence of Scientific and Biblical Wisdom (1997)

I wouldn’t recommend this book to anyone frankly. It is mildly interesting, but ultimately unsatisfying when it comes to the religion vs. science debate.[ref]It might be worth noting that atheist philosopher Antony Flew was impressed by Schroeder’s arguments, which helped move him to embrace a form of deism late in life.[/ref] However, it was Schroeder that made me actually look at the debate. My interest in science and the history of science can be traced back to this book. Furthermore, it is the reason I became quite comfortable with biological evolution. Prior to my mission, I hadn’t given evolution a thought. I gave it superficial attention on my mission, drawing largely from outdated, anti-evolution quotes (still) found in the Church’s institute manuals.[ref]I remember being called a “hybrid Mormon” one time because I answered the evolution question with, “I don’t personally believe it, but if that’s how God did it, I’m fine with that.” This was my answer for some time.[/ref] But it was Schroeder’s book, which I picked up at a Barnes & Nobles (?) one P-Day,[ref]Mormon missionary lingo for “preparation day,” which was basically our day off. We were supposed to “prepare” for the rest of the week by doing our grocery shopping and the like. Most of us took it to mean “Play Day” and that’s what we did.[/ref] that made me think differently. Despite being critical of the theory (he is one of the contrarian scientists in Ben Stein’s documentary Expelled: No Intelligence Allowed), he provided a new paradigm by drawing on ancient Jewish scholars such as Rashi, Maimonides, and Nahmanides. This helped me think about my own faith’s approach to science and I found myself defending evolution against fellow missionaries by the end of it all.

I wouldn’t recommend this book to anyone frankly. It is mildly interesting, but ultimately unsatisfying when it comes to the religion vs. science debate.[ref]It might be worth noting that atheist philosopher Antony Flew was impressed by Schroeder’s arguments, which helped move him to embrace a form of deism late in life.[/ref] However, it was Schroeder that made me actually look at the debate. My interest in science and the history of science can be traced back to this book. Furthermore, it is the reason I became quite comfortable with biological evolution. Prior to my mission, I hadn’t given evolution a thought. I gave it superficial attention on my mission, drawing largely from outdated, anti-evolution quotes (still) found in the Church’s institute manuals.[ref]I remember being called a “hybrid Mormon” one time because I answered the evolution question with, “I don’t personally believe it, but if that’s how God did it, I’m fine with that.” This was my answer for some time.[/ref] But it was Schroeder’s book, which I picked up at a Barnes & Nobles (?) one P-Day,[ref]Mormon missionary lingo for “preparation day,” which was basically our day off. We were supposed to “prepare” for the rest of the week by doing our grocery shopping and the like. Most of us took it to mean “Play Day” and that’s what we did.[/ref] that made me think differently. Despite being critical of the theory (he is one of the contrarian scientists in Ben Stein’s documentary Expelled: No Intelligence Allowed), he provided a new paradigm by drawing on ancient Jewish scholars such as Rashi, Maimonides, and Nahmanides. This helped me think about my own faith’s approach to science and I found myself defending evolution against fellow missionaries by the end of it all.

5. The Norton Anthology of World Literature, Vol. D-F: 1650 to the Present, ed. Sarah Lawall, Maynard Mack (2002)

In elementary school, I was part of a “gifted and talented” program called EXPO (EXceptional POtential). One of its perks was that I was allowed to attend an EXPO course during regular class time. Most the time, EXPO was much more fun than your everyday class. However, when I arrived in middle school, I found that EXPO was during my English class. English had been my favorite subject for years, which is why I quit going to EXPO after one class because I didn’t want to miss it. This love of English stayed with me up to my World Literature course in my early years of college. I had recently returned from my mission, during which I had been trying to understand the history, language, and culture of the scriptures as well as Christian history generally. This anthology was required for the course and it immersed me in multiple voices from a variety of times and cultures. It included works by Yeats, Proust, Lu Xun, Joyce, Woolf, Kafka, and more. It reminded me that there is so much to learn and that my studies should not only be cross-cultural, but interdisciplinary. In short, reading this anthology was my first big taste of one of the grand fundamental principles of Mormonism: “…receive truth, let it come from whence it may.”[ref]Unfortunately, my fiction reading basically died that same year. I was largely non-fiction until recently.[/ref]

6. C.S. Lewis, The Screwtape Letters (1942)

I had never read any C.S. Lewis prior to my mission. A ward member bought Elder Anderson and I copies of The Chronicles of Narnia for Christmas one year, but I never read any of Lewis’ philosophical/apologetic writings until my first year of marriage. I still remember quite clearly lying in bed in our first apartment reading the first chapter (letter) of The Screwtape Letters and being struck by the following (from the demon Screwtape to his nephew Wormwood): “Your business is to fix his attention on the stream [of immediate sense experiences]. Teach him to call it ‘real life’ and don’t let him ask what he means by ‘real’.” I also remember asking myself afterwards what exactly I meant by ‘real’.[ref]This portion comes from a post at The Slow Hunch.[/ref] It could be said that Lewis’ book was my first introduction to the importance of metaphysics. This led to later works on metaphysics, from Blake Ostler to David Paulsen to Edward Feser to David B. Hart to Stephen Webb. My current outlook is similar to Rosalynde Welch’s “disenchanted Mormonism,” but I imagine it will continue to change as metaphysics play an increasingly important role in my theological framework and overall worldview.

I had never read any C.S. Lewis prior to my mission. A ward member bought Elder Anderson and I copies of The Chronicles of Narnia for Christmas one year, but I never read any of Lewis’ philosophical/apologetic writings until my first year of marriage. I still remember quite clearly lying in bed in our first apartment reading the first chapter (letter) of The Screwtape Letters and being struck by the following (from the demon Screwtape to his nephew Wormwood): “Your business is to fix his attention on the stream [of immediate sense experiences]. Teach him to call it ‘real life’ and don’t let him ask what he means by ‘real’.” I also remember asking myself afterwards what exactly I meant by ‘real’.[ref]This portion comes from a post at The Slow Hunch.[/ref] It could be said that Lewis’ book was my first introduction to the importance of metaphysics. This led to later works on metaphysics, from Blake Ostler to David Paulsen to Edward Feser to David B. Hart to Stephen Webb. My current outlook is similar to Rosalynde Welch’s “disenchanted Mormonism,” but I imagine it will continue to change as metaphysics play an increasingly important role in my theological framework and overall worldview.

7. Thomas Sowell, Applied Economics: Thinking Beyond Stage One (2004)

I became a Sowell admirer by reading his weekly columns when I was first becoming interested in politics, but it was this book that made me fall in love economics. I ended up reading his other works soon after, including Black Rednecks and White Liberals, Intellectuals and Society, A Conflict of Visions, Economic Facts and Fallacies, etc. All of these had their own influence, but it was Applied Economics that started it all. What made this different from, say, his Basic Economics was that it looked at economic effects in the real world and explored the unintended consequences of particular choices and policies. It showed what he calls the “constrained” or “tragic vision”[ref]This is explored in his A Conflict of Visions: Ideological Origins of Political Struggles.[/ref] (i.e. there are no solutions, only trade-offs) in action. It aided in my understanding of economics as not merely models and math, but behaviors, emotions, relationships, and everyday choices.

8. Daniel H. Pink, Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us (2009)

I was originally an accounting major as an undergrad. However, I both hated accounting and sucked at it. Realizing I was too far into my business degree to consider a complete change, I ended up choosing Organizational Behavior and Human Resource Management (mainly because it sounded better than Business – General Studies). I didn’t have much interest in management or business outside of the practicality of a business degree until I had to do a group project on organizational culture in my HR course. In my research, I came across Dan Pink’s TED talk on human motivation. The focus on autonomy, mastery, and purpose in the workplace made me look at businesses in a different light; as organizations or communities of people rather than abstract entities. Organizational theory and management literature became a way of assessing the human condition. Business can be a practice pregnant with meaning, joy, and moral significance. The reason it often isn’t is because, as Pink puts it, there is “a mismatch between what science knows and what business does.” A desire to understand and possibly help repair this chasm was a major factor in my decision to pursue an MBA.

I was originally an accounting major as an undergrad. However, I both hated accounting and sucked at it. Realizing I was too far into my business degree to consider a complete change, I ended up choosing Organizational Behavior and Human Resource Management (mainly because it sounded better than Business – General Studies). I didn’t have much interest in management or business outside of the practicality of a business degree until I had to do a group project on organizational culture in my HR course. In my research, I came across Dan Pink’s TED talk on human motivation. The focus on autonomy, mastery, and purpose in the workplace made me look at businesses in a different light; as organizations or communities of people rather than abstract entities. Organizational theory and management literature became a way of assessing the human condition. Business can be a practice pregnant with meaning, joy, and moral significance. The reason it often isn’t is because, as Pink puts it, there is “a mismatch between what science knows and what business does.” A desire to understand and possibly help repair this chasm was a major factor in my decision to pursue an MBA.

9. Matt Ridley, The Rational Optimist: How Prosperity Evolves (2010)

In his many lectures and interviews,[ref]These influenced me far more than, say, Capitalism and Freedom, mainly because I’d watched many of them before I ever read any of his books.[/ref] famed economist Milton Friedman often encouraged his audience to have a sense of proportion. It is easy to look at anecdotal evidence or snapshot data and draw conclusions about the world. Ridley’s book provides the evidence for Friedman’s “sense of proportion.” He documents how prosperity emerged and evolved over hundreds of thousands of years via specialization and exchange. This helped me look at major problems like poverty from both a global and historical perspective. More important, it helped me take typically leftist crusades like “social justice” seriously and thus led to my embrace of a kind of bleeding-heart libertarianism. By tracing the rise of living standards over the centuries, I came to see how important trade and innovation are to the improvement of human well-being. It also left me just a tad more optimistic about the future.

10. Deirdre N. McCloskey, Bourgeois Dignity: Why Economics Can’t Explain the Modern World (2010)

On a panel at Beyond Belief 2006, astrophysicist and popular science educator Neil Degrasse Tyson made an insightful comment while (kindly) rebuking the (in)famous Richard Dawkins for his rhetorical methods: “Being an educator is not only getting the truth right, but there has to be an act of persuasion in there as well. Persuasion isn’t always “here’s the facts, you’re either an idiot or you’re not.” It’s “here are the facts and here is a sensitivity to your state of mind.” And the facts plus sensitivity, when convolved together, creates impact.” Rhetoric today has a rather negative connotation, one associated with cheap emotionalism or a lack of substance. However, McCloskey’s book argues that it was rhetoric–the act of persuasion or, more to the point, the power of words–that caused and sustained the Industrial Revolution. The bourgeoisie (i.e. the professional and educated class) were praised and seen as dignified and free. This shift in opinion changed the social and political spectrums. Far more than an excellent work in economic history, this book demonstrated to me how words and ideas, along with the way they are articulated, ultimately have the ability to transform societies. Rhetoric can inspire brand new thoughts or even recast old ones in a new light. This in turn has inspired me to be careful and selective in my choice of words and phrasing when expressing my ideas.

On a panel at Beyond Belief 2006, astrophysicist and popular science educator Neil Degrasse Tyson made an insightful comment while (kindly) rebuking the (in)famous Richard Dawkins for his rhetorical methods: “Being an educator is not only getting the truth right, but there has to be an act of persuasion in there as well. Persuasion isn’t always “here’s the facts, you’re either an idiot or you’re not.” It’s “here are the facts and here is a sensitivity to your state of mind.” And the facts plus sensitivity, when convolved together, creates impact.” Rhetoric today has a rather negative connotation, one associated with cheap emotionalism or a lack of substance. However, McCloskey’s book argues that it was rhetoric–the act of persuasion or, more to the point, the power of words–that caused and sustained the Industrial Revolution. The bourgeoisie (i.e. the professional and educated class) were praised and seen as dignified and free. This shift in opinion changed the social and political spectrums. Far more than an excellent work in economic history, this book demonstrated to me how words and ideas, along with the way they are articulated, ultimately have the ability to transform societies. Rhetoric can inspire brand new thoughts or even recast old ones in a new light. This in turn has inspired me to be careful and selective in my choice of words and phrasing when expressing my ideas.

Here are a few honorable mentions with very brief explanations as to why:

- Ingri D’Aulaire, Edgar Parin D’Aulaire, D’Aulaires’ Book of Greek Myths (1962): I read this book over and over in elementary school. Where my love of Greek and Roman mythology came from.

- Ian Fleming, Casino Royale (1953): I’m a huge Bond fan and this is still my favorite Bond novel.

- Rodney Stark, For the Glory of God: How Monotheism Led to Reformations, Science, Witch-Hunts, and the End of Slavery (2003): Gave me a far greater love of medieval Christian history: a time frame that has been lambasted by Protestants, secularists, and Mormons alike.

- N.T. Wright, Surprised by Hope: Rethinking Heaven, the Resurrection, and the Mission of the Church (2008): Also played a role in my embrace of the social justice cause via a more “earthy” ministry and Wright’s “new creation” theology.

- Peter Drucker, The Essential Drucker (2001): Hayek is my philosopher economist, Drucker is my philosopher manager.

- Jim Butcher, Storm Front (2000): I’m going out on a limb with this one, but this may have major future repercussions. It it is the first in The Dresden Files (I need to begin #13: Ghost Stories) and it was recommended and given to me as a birthday gift by Nathaniel. I hadn’t read a fiction book in years prior to it. I think it very well may be beginning of my love affair with fiction. We’ll see once I finish the entire series.

I kind of wish my list was a little different, but it is what it is. This will surely change in the future. I probably missed some too. But this is what I can come up with as of now. Hope you enjoy.

Thanks, Walker! I’ve been really looking forward to this and I had a lot of fun reading it.

Your post also made me wish I’d come across Calvin and Hobbes earlier in my life. Sadly, I discovered and loved The Far Side first. Which, while quite excellent in its own way, isn’t the monument to poignant humanity that C&H is.

Thank you for these recommendations. You’ve bumped up my reading list nicely for this month. My best recommendation would go to Chip Mendez’s The Millionaire In The Next Cubicle. http://www.chipmendez.com

It’s no exaggeration to say that book has changed my life. I have always made terrible financial and career decisions but reading this book has taught me a lot of new philosophies and ideas that have had a huge impact on my life. Fantastic book.