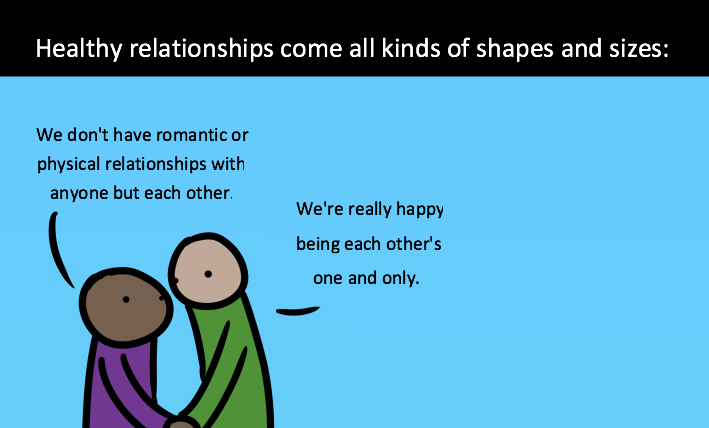

EverydayFeminism.com would like you to know that healthy relationships come in all shapes and sizes. The image starts with a monogamous couple (albeit gender-neutral) and then depicts a variety of relationships including:

- Asexual (“We don’t have sex… but we sure enjoy cuddling!”)

- Mixed Sexual/Asexual (“She fills her sexual needs with other people.”)

- Open (“We also have romantic and sexual relationships with other people. That doesn’t make our love any less valid.”)

- Polyamarous (“We do have to take turns for who gets to sleep in the middle” / “Tonight it’s me! I’m going to get all the cuddles.”)

- BDSM / Kink (“Who’s a good boy?” / “ruff”)

- None (“I’m happy flying solo.”)

The one thing that all of these relationships have in common is that they are defined exclusively in terms of their utility to the voluntary participants. Once you accept that premise, the rest follows. If relationships exist for the pleasure, security, comfort, and fulfillment of the parties to the relationship, then any relationship that meets those needs is an equally valid relationship.

It’s a nice picture, but it’s leaving somebody out. This is a worldview for the privileged and the powerful. Not in terms of gender or sexuality or class distinctions, but in terms even more profound: adults vs. children. Children have no vote about the relationships they enter into. They get no say in the circumstances of their conception, nor do they have any influence over the environment in which they are raised. They are truly and completely powerless and vulnerable.

Because children are held hostage to the behavior of the adults who care for them, they will face the consequences–for good or ill–of how adults choose to manage their romantic lives. Regardless of how effective polyamorous, asexusl[ref]Yes, I’m aware of where children come from, but just as someone in a homosexual relationship today might have children from a past relationship, so might someone in an asexual relationship[/ref], etc could be at providing a good home for children, that only works if children are in the picture to begin with. How can a theory of romantic / sexual relationship that doesn’t even admit to the existence of children possibly serve to protect their interests? It can’t.

As positive as it may attempt to be, what this image implies (but does not show), is a world where the needs of children come a definitive second to the adult pursuit of happiness.

Is this different from any of the other major choices adults make? Occupation, religion, location–we assume adults who care for children will make these decisions with them in mind, but that’s the only sense in which the children get a say. If the message is that there are lots of relationship structures people could entertain, and no one from outside those relationships is well-placed to judge them, that would seem as reasonable to me as making the same point about choosing to live in Rwanda or to join the military. That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be aware of potential costs to children of these choices and, where possible, offer to help offset those for families we care about.

Kelsey-

I think it has a much greater impact than, for example, occupation or religion or location, because it (often, not always) involves who lives in the same home as the child.

I’m not going to say there’s nothing else that could have a similar impact, of course. Joining the military is actually a pretty good one that would have at least a similar scale of impact. Which is one reason, for example, that the military asks you about any dependents before you join up and requires you to show what your plan is to care for those dependents. Because there’s such a big impact on children with a decision like that, there are actual policies in place to recognize that fact. Not gonna say they are perfect or anything, but at least it does what I’m saying we should do: keep the rights and needs of children in the picture.

“How can a theory of romantic / sexual relationship that doesn’t even admit to the existence of children possibly serve to protect their interests?”

Well, there are many people in relationships like these who have successful children, so lets not jump to “it can’t!” just yet.

This critique sounds like criticizing a sedan because, what in the world will you do if you buy a couch and need to get it home?!? You can’t have a couch if you buy a sedan because it’s not designed with that in mind!

Does this mean every household should have one pickup and one minivan in the driveway as God intended? Only for people who don’t know about delivery vans, or Ikea couches you put together at home, or futons. Maybe they don’t want a couch.

Being in one of the listed relationships isn’t a declaration one way or another about its fitness for if you have a kid one day.

Ryan-

I’m not making the case that these relationships are not suited to raising children. I very consciously sidestepped that issue. My argument is different. It’s that *no* relationship is suited to raising children if suitability for raising children isn’t part of the consideration from the beginning.

In other words: my problem with this graphic is not that it has relationships other than monogamous, heterosexual. My problem is that there are no children on it anywhere. In that regard all the depicted relationships (including the monogamous one) are equally problematic.

I’m saying that when adults think about what makes relationships healthy, children should be at least in the picture.

“My argument is … that *no* relationship is suited to raising children if suitability for raising children isn’t part of the consideration from the beginning.”

People have raised children successfully in any number of accidental, stumbled-into, non-ideal scenarios that didn’t plan for kids. That’s usually not the best way to start out, but your argument that it “no such relationship is suited to raising children” is obviously false.

“I’m saying that when adults think about what makes relationships healthy, children should be at least in the picture.”

If they want kids, yes, obviously. The illustrated people don’t want kids. To whom is it news that priorities change when kids are considered? Trust me: Nobody in the 25-40 age bracket isn’t reminded to consider kids regularly.

I realize it’s confusing to many family-oriented folks that people enjoy relationships for years/decades without kids entering the picture. Childless couples don’t lecture parents on how to conduct their relationships, so…

Suggesting that people should make decisions with the interests of their children in mind is excellent, but it’s clearly different from giving them a say, which was the phrase that struck me as far too strong. It seems to me that we generally assume that adults are capable of taking responsibility for the consequences of their decisions (knowing that, sadly, we often fail). While it’s true that none of these examples of relationships explicitly considers children, none of them explicitly consider the impact on your work life, or your relationship with your extended family, or any of the many other things which would likely be affected by such a choice. Yet no one would look at these images and suggest that they couldn’t be well-suited to holding a job because the role of a job isn’t baked into them. We take it for granted that a competent adult will be better positioned than an outsider to infer those effects and weigh them.

Similarly, the choice of how many children to have and whether a widow/er should remarry affect the people who are at home. We expect that parents make these choices with children in mind, but that’s where it ends.

All of which said, I’m generally sympathetic to the concern that children aren’t as salient in some places as they ought to be. As someone who has always loved children, it struck me about halfway through my undergraduate career that there were very few of them on campus. I was fortunate to get some summer jobs involving kids and do a little coaching on the side, but an awful lot of my peers spent four years with almost no exposure to children, and did so during prime thinking-about-mating time. I’d really like to see that change, and would like information about what children need to be more salient to more people.

What I don’t want is to judge people in non-traditional relationships for their failure to provide the ideal circumstance for their kids. All the data we have are aggregated; in any particular circumstance, those choices might be best for that family. I fear that the disapproval of others might well be all that separates those averages, and would rather not contribute to the problem.

Ryan-

Let me try this again. I wrote: “My argument is … that *no* relationship is suited to raising children if suitability for raising children isn’t part of the consideration from the beginning.” What I should have said (and what I was thinking of) is that no conception of relationships is suited to raising children if suitability for raising children isn’t part of the consideration from the beginning.

You (and Kelsey too, I think) are both thinking in terms of real-world instances of relationships. My point wasn’t about particular relationships. It was about the way that we think about relationships. The illustration shows that people are thinking about relationships in a highly individualistic sense: the relationship is evaluated for health purely in terms of the adult participants.

I think that–as a general rule–US society is already too individualistic. I think we tend to atomize individuals in ways that are counter to human nature and therefore bad for individuals and for society in the long run. So I’m just saying “No man is an island,” and that–as an extension–no particular relationship of men/women is an island either. We’re all interconnected.

Obviously this can go too far in the other direction, but what I’m suggesting is simply that we moderate a bit from the current emphasis on individualism to include a more communitarian conception of human nature including relationships.

If you asked me “what is a healthy relationship?” it would first and foremost consider the voluntary, adult participants, but it wouldn’t stop there. And the most important consideration (after the primary participants) is children.

Again, this isn’t children in particular. I’m well aware that lots of folks go long periods of time (up to and including entire lives) without having kids either by deliberate choice, because they have no choice, or because their lives just never lead in that direction. I am not criticizing any of those folks. But it is also very much the case that sometimes kids come into a relationship without the conscious, deliberate decision of all parties to the relationship. You might date someone who already has a kid. Something could happen to a child’s primary guardian making one of the partners in the relationship have to consider taking over that role. Or, in the dominant case, one of the partners might get pregnant without a conscious decision to have kids (maybe birth control fails, maybe not both partners agreed, maybe they just weren’t thinking about it.)

I’m not saying that such a relationship can’t be re-organized to respond to new circumstances. It can. I’m also not saying that every relationship that includes kids as a consideration from the get go succeeds. They don’t. I’m just saying that if we’ve got a society where the emphasis almost exclusively on evaluating, conceptualizing, and organizing relationships only with adult interests in mind, this will be bad for kids in aggregate. Because in the real world lots and lots of children (arguably: the majority) are conceived in relationships that were not tailored to their interests. So it is a very prominent problem and it has real, negative consequences for children and as a result for all of society. This illustration is not Exhibit A, but it is relevant to the issue. We–as a society–tend to think of relationships as means to ends, where the ends are the happiness and fulfillment of adult participants and that’s it. We think they can be reconfigured or refocused if/when the adults decide to have kids, but that’s just not how kids actually enter the picture. It’s not always the result of a deliberate decision. And in those cases (most of the cases) the result is a handicap for the kids (and probably the participants as well.)

Does this make more sense?

Kelsey-

The difference for me is that an employer doesn’t have any kind of unconditional moral or legal right to be cared for / provided for by anyone. So if a relationship isn’t conducive to a particular line of work (and quite a lot of them are not): who cares? But children do have a legal and moral claim on their parents (and require a lot more commitment than most jobs), and so i think it’s a different situation.

That’s a really profound observation, and I agree with it.

I’m very much trying to stay away from that. But I do think it is possible and even important to talk about good/bad aggregate behavior while stipulating that because there are exceptions, the good/aggregate behavior question cannot be used to judge any individual case.

What’s more, I’m really talking about a conception of relationships that is totally universal. A heterosexual, monogamous couple can be exactly as prone to this kind of relationship paradigm as any other relationship configuration. This isn’t a stealth attack on same-sex or other kinds of relationships. It really isn’t. It’s a statement that I am concerned by the prevalent paradigm that sees romantic relationships almost exclusively in terms of the happiness and fulfillment of the participants. That matters, obviously, and it matters a lot. But there’s more to a romantic relationship than that. Or, rather, there ought to be.

I won’t speak for Ryan, but that makes sense to me. I actually think that broadening the discussion beyond children would make it less fraught. While various relationships might be healthy for the individuals involved, other things being equal, they might not be equally well-suited to interfacing with the rest of society and supporting the participating individuals in their attempts to satisfy their obligations. I support individuals considering how their relationships will influence their ability to have children, care for elders, and participate in their communities with the understanding of how those communities actually function (for example, how insurance standards and hospital visitation work).

I also think there’s a moral hazard problem in identifying relationships which are bad for society, and especially for children–if I have it in mind that someone is doing bad things to a child by choosing the relationship they have, I am likely to refuse to accommodate that relationship and thereby make it even worse for the child. I don’t think elevating the discussion a level of abstraction fixes this problem–the condemnation of some relationship types as poorly suited to satisfying social obligations seems to follow from it. Over-attentiveness to the problem of moral hazard in such judgments leads less careful thinkers into a troubling and intellectually bankrupt moral relativism. But there’s ample evidence that it is a genuine problem worth weighing.

Apologies–I started my last reply before your last. In response to that, I have nothing but approval.

Nathaniel: “I’m just saying that if we’ve got a society where the emphasis almost exclusively on evaluating, conceptualizing, and organizing relationships only with adult interests in mind, this will be bad for kids in aggregate.”

If all of society was organized as adults-only I’d be worried, but all we’ve got is a cartoon that’s adults-only. Clearly society’s evaluations of relationships considers children in practice. It’s a slippery slope to use potential kids as a basis for discouraging behavior between adults.

Ryan, I’m not saying you’re wrong, but I don’t feel like I connect well with the potential places we might slide on that slippery slope. What things might be bad for adults to do if they’ll one day have kids which they might choose not to do because of that possibility? Most of the things which come to mind for me would be pretty good to avoid, independent of children, like crushing debt, addiction, or using your real name to comment on blogs. Perhaps making widely-available pornography. Not exactly a parade of horribles, though, admittedly, I’d be happier if our society were a bit more reliably chilled-out about sex work.

So, my imagination is largely failing me. What desirable options would we be foregoing by considering children more?

“It’s a statement that I am concerned by the prevalent paradigm that sees romantic relationships almost exclusively in terms of the happiness and fulfillment of the participants.”

Exactly, Nathaniel. That idea has dominated our culture for decades, and I’m not seeing healthier families as a result. And your comments on our individualistic and atomized society — that’s why I am not a libertarian.

This from Ryan: “People have raised children successfully in any number of accidental, stumbled-into, non-ideal scenarios that didn’t plan for kids.”

What is the definition of “successfully” here? I fully support single parents, unplanned babies, etc. I am a strong believer in supporting the orphans and widows, in redemption after poor decisions, and in life regardless of imperfect circumstances. I know there is much value to suffering. But we have to allow those children to mourn their losses. We deny them that when we pretend all these life arrangements are healthy. We essentially communicate that their suffering is merely their flawed perspective. If only they just understood things differently, all would be well, right? I have seen this play out time and again in our divorce and re-marriage culture. As long as kids grow up to be “successful”, we shouldn’t make any general judgments about family relationships.

This impacts kids across the board even if we are just trying to reaffirm lifestyle choices for couples who do not have children. Until recently, we understood that even adopted kids had experienced a life-long loss, and the goal for adoption was to restore what was lost as best as possible, with coping techniques addressing biological parent issues that eventually arise. Now we want to pretend like the loss isn’t even there as we increasingly expand our definitions of healthy. Now we intentionally create children separated from biological parents with various technologies, no longer making it a tragedy beyond our control, just more roads to adult fulfillment. And the kids are supposed to be grateful.

Are we really going to tell some of those people in the link that their relationship is healthy except when raising children? They are defined as healthy relationships, right? Wouldn’t we be denying them personal fulfillment on their own consensual terms, the litmus test for morality in our culture? Wouldn’t we risk hurting their feelings? We are suing people over hurt feelings these days. Will kids even have permission to articulate their hurt feelings resulting from their caregiver’s lifestyle choices with this push to view all these relationship options as healthy? Value judgments on sexual relationships among adults must consider children, on personal and societal levels, because sex is naturally oriented toward the creation of children and family. We aren’t playing golf here. This is not a consequence-free recreational activity, even with the knowledge that some populations are infertile. We are already making decisions about technology and legislation based on this cultural philosophy of adult relationships, and kids are largely expected to embrace it and get over it much to their detriment.

Kelsey, a quote straight from my sister…”The decision of who to marry/partner up with hits at the core of the child’s existence, identity and family of origin. It carries a different weight than other life decisions.” It’s different than career choice and other adult decisions. And while a military career does involve loss and sacrifice for children, at least we openly acknowledge the loss. That’s half the battle for healthy relationships.

I guess I don’t see “healthy” as synonymous with “perfect”. If it helps, consider the many imperfections in even the best child-raising families of your acquaintance. No one does everything right, and the ways we do things wrong have real costs. What it means to me to say that a relationship can help raise successful children is tied to our everyday definitions of success–able to function in the world well enough to perform a valuable role flexibly and form stable, healthy attachments with others. That leaves a lot of room for problems, but I’m not big on casting stones on that score. Is anyone?

With respect to your sister, I think she’s wrong–whether to have another child carries a similar weight, and, as you concede, certain choices about what job to take or, in extreme cases, where to live (I’m thinking about moving from a conflict zone to the United States as an example) can have an impact of similar magnitude. My experience with military families is not copious, but neither is it nothing, and my impression is that spouses and children are expected to support the career of the service member in their family, to regard it as a uniquely noble pursuit, and to be willing to uproot their lives whenever his or her career requires it. Contrariwise, I’ve seen no expectation that adopted children and children of divorce don’t suffer or shouldn’t acknowledge a cost to them. Perhaps we simply have different experiences, but I simply don’t see the patterns in actual behavior you seem to.

Nathaniel is probably correct that simply choosing your relationships with children and other social obligations in mind helps us frame our lives in ways which tend to be helpful. I think that goal is entirely consistent with avoiding attaching any sort of stigma to unfamiliar relationships.

I definitely see the expectation with kids of divorce, both personally and culturally. But if it helps, I will re-phrase: The cost to kids is considered acceptable in our culture for the perceived greater good of adult fulfillment. I’m not talking about abusive situations – I’m talking primarily about no-fault divorce here, which follows the current romantic relationship outlined in this blog post.

I have personally been told that, “I should be happy for my parents,” and, “I have all these extra people to love me,” and my parents “successfully” raised me, and 50 other stupid (sorry), dismissive comments. I am not unique. In fact, I have it better than most with loving, mature parents in loving, mature (different) marriages, and they have good relationships with us, their grown kids. People measure my parents’ divorce on outcome – just like some of the comments in this com-box. My parents are now happy, their kids are successful, and the divorce was therefore a good thing. Success! It is typical ends justifying the means. But the divorce was not good. It caused lasting, irreparable harm to my family despite our “success” that only gets harder as we age, and my dad was following classic adult-fulfillment philosophy when he walked out on us so many years ago. I am *only* in a healthy marriage today because of A) God, who can overcome all things, and B) I recognize that my dad was fundamentally wrong when he left our family, regardless of positive outcomes. I don’t justify it. That’s part of the healing process. I owe my healthy relationships and stability to the fact that my mom, especially, understood this and never dismissed, sugar coated, or minimized, while simultaneously remaining respectful toward my dad. Tough woman! Most kids of divorce aren’t so lucky, and our culture enables this behavior and dismissive attitude. The more progressive idea – that all consensual relationships are equally healthy – contributes to the dysfunction.

I see this problem more and more with adoption – How can we continue to acknowledge the profound loss of biological parents of an adopted child while we simultaneously create babies via technology and intentionally separate them from their biological parents? How can we take their loss seriously when we call egg donations, sperm donations, and genetically engineered babies a societal good? I guess we can concede a cost while adopting the philosophy – again – that the fulfillment of the parents is the greater good here. But the cost has been minimized. It’s no longer about restoring a loss for the child, but fulfilling a desire in the adult participants. Once a life is created, that person has infinite value. But I refuse to call this process good. It is, however, an extension of the same philosophy and does impact traditionally adopted children.

I agree — healthy does not equal perfect. I don’t think anyone was under that impression. No one has a perfect life. And often kids are successful *despite* their parents’ choices or life circumstances, not because of them. That doesn’t justify bad choices or unhealthy relationships, though.

I’m not arguing for the eradication of imperfect family structures – just that we, as a society, acknowledge structures that are fundamentally unhealthy and aim to reduce them through the healing of future generations. I am not seeing healed future generations in the U.S. currently. I am seeing a lot of heartache and dysfunction. I’m not afraid of a stigma – the truth is very freeing. And love doesn’t make excuses or justify unhealthy situations.

I certainly don’t want to minimize your experience, but one way to interpret the sorts of comments you’ve reported is that people are trying to help you look on your parents’ divorce in the most positive light possible. That doesn’t mean it’s overall a good thing, only that we should celebrate the good elements of tragic circumstances because it’s psychologically helpful. I don’t see that as necessarily more dismissive than any of the ways people suggest taking comfort in faith in times of crisis.

Similarly, parents in relationships of all types will sometimes make genuinely poor decisions about whom to allow into (or eject from) their home, with heartbreaking consequences for children. But there will be people in each of these types of relationship who consider their children when entering them, and make good choices for them. Is there some reason to expect your access to God or judgment about the quality of your parents’ choices is inaccessible to people who’ve lived in polyamorous or other unusual homes?

As for adoption, it’s different to be abandoned by a parent once born than to have had a donor supply an egg or (millions of) sperm. No one gets attached to their individual gametes, so it doesn’t carry the same sense of rejection. Furthermore, the particular sperm and egg which go into making a test-tube baby would never have made a person but for the technology, so the set of options for the child never included birth into a biologically-related two-parent family. Between existence in a biologically unrelated (or half-related) family and no existence, it’s hard to make a case that we wrong such a child by selecting the first. And I don’t even know where you’re coming from with genetically engineered babies–maybe this is news I just haven’t read yet, but it sounds like you’re projecting social approval onto technology which doesn’t yet exist.

You’re right that children’s success despite poor circumstances doesn’t justify the choices which led to those circumstances. Sufficient success, though, absolutely does undermine the claim that those circumstances were actually bad. You say you’re not seeing healed future generations, but my impression is that we have the lowest crime rate in our history. If people are so dysfunctional and wounded, why are we so much better at controlling our violent impulses? Maybe that’s not the best measure of dysfunction (though it seems like a plausible enough one)–is there a different one you prefer, or are we restricted to anecdote?

Kelsey-

LT can weigh in herself, of course, but I think that the motivation may be accurate, but the consequence is still the same: the pain of divorce is kind of minimized. It’s also impossible to separate out cleanly the motive of people who want children of divorce to feel better vs. the motive of people who want divorced parents to feel better. When are we really trying to make kids feel better vs. when are we trying to make ourselves feel better?

This is one that surprises a lot of people (including me, when I first started to learn about it), but kids who were created by IVF actually do have a real sense of rejection. I agree that it’s philosophically difficult to compare not-being-created to any particular creation, but for these kids the fundamental notion is that they feel they have a right to their genetic parents. And I think they make a compelling argument. At least, their experiences are very hard to ignore.

I will try to find you some of the interviews and the groups that I’ve read about and repost them here.

LT, I owe you an apology. In poking around a bit for examples of IVF children who resent their existence, I ran across articles about a technique, not currently approved anywhere but technologically possible, for inserting the mitochondria of a third person into a zygote (to prevent the transmission of genetic disorders caused by mitochondrial DNA). While I don’t think this is technically genetic engineering, it’s certainly close enough that a lay understanding could be naturally construed to include it. So my dismissive tone about this possibility was born of ignorance, I apologize.

That said, it’s pretty awesome. The separability of mitochondrial DNA from the DNA in the nucleus and its exclusion from the normal process of inheritance means that I’m less attached to it than I normally would be. The discovery that my children don’t share my mitochondrial DNA would be no discovery at all–I’m male, and fathers make no contribution to their children’s mitochondria. They’re sort of like in-cell symbiotes, a middle ground between one’s own DNA and the DNA of the many gut bacteria we all need to digest, but don’t regard as central to our identity. More importantly, a dear friend of mine has a genetic disorder of sufficient severity that she has chosen not to pass it on. If she knew she could fix that one problem, and then pass on half of the rest of her excellent DNA and have a biological child with her nearly equally exemplary husband, I have difficulty imagining that anyone who knew them wouldn’t celebrate.

Nathaniel, I understand your point that people feel as though their pain is minimized, but if that’s not the intent of the speakers, the inference to a growing cultural denial of that pain is missing. I get that it’s traumatic, and certainly don’t blame a child of divorce for hearing those words as dismissive, because it’s understandably difficult to listen charitably in those circumstances. With respect to the IVF children, I’ll reserve judgment. The one case I found in a Google search made the girl seem sort of dramatic and lacking in perspective, but I wouldn’t want to judge all of those who feel similarly based on that example, so at this point all I have to go on is the philosophy.

While individuals may have been trying to help kids see their parents’ divorce in the most positive light, the cultural impetus was definitely to simply minimize the effects of divorce in order to justify it. I’m too lazy this morning to dig up citations, but psychologists spent the 60s to 80s not only arguing that divorce isn’t bad for kids but that it’s quite possibly good because kids gain new role models in their lives as parents date. Fathers were essentially written off as not important in the lives of their children.

We know now that, in fact, divorce is generally bad for children (only becoming good in the instance that it outweighs a greater evil like abuse or extreme marital conflict), fathers are important, etc. so these days we just ignore children, as Nathaniel has been talking about.

As a side note, it drives me absolutely batty when I hear ‘the kids turned out ok in x situation, so x situation is ok.’ The fact that the kids don’t run to the nearest drug den or suicide booth doesn’t mean damage hasn’t been done. Children are remarkably resilient and good at hiding the effects of their experiences. I used to say the same thing to myself, that everything is fine, and then I took a deep look inside myself and realized that ‘functioning’ and ‘healthy’ are not the same. I also read studies on children of divorce, and I discovered what I considered normal because I didn’t know any better was in fact the effects of divorce (for example, perpetual anxiety about relationships ending).

This is probably my favorite paper (it’s based on a book) on the matter:

http://www.fellowshipoftheparks.com/Documents%5CUnexpected_Legacy_of_Divorce.pdf

No worries, Kelsey. I am taking a wide definition of genetic engineering here. And I actually support ethical therapeutic treatments for babies in utero. I don’t support creation by in vitro, but genetic therapies could be a good thing. We are already debating the ethics behind choosing your child’s physical and intellectual characteristics, though, because we know the option is around the corner.

We can recognize a person’s intrinsic value and still understand that their conception was immoral. You wrote, “Between existence in a biologically unrelated (or half-related) family and no existence, it’s hard to make a case that we wrong such a child by selecting the first.” Would you make that argument for a child conceived in rape? In infidelity? Would we argue that those types of conception are good, because the child would not have existed otherwise? One’s existence does not moralize their conception. And I think it is unfair to silence these kids and their struggles by throwing their existence back in their face.

As far as dismissive comments, Nathaniel is correct. And I will add that I give individual people the benefit of the doubt when they make comments to me. I assume they are just trying to help unless I know otherwise. But those comments are used by adults to justify leaving their families. They are used by step-families to dismiss their step-children’s valid struggles. My dad still says stuff like that — I don’t think he has fully taken responsibility for his actions. My mom has clarity; my dad doesn’t. He sees the good that resulted and uses it to justify his actions. These lines make up an internal dialogue for adults who want to justify their actions. And our culture echos those lines back to the kids in an effort to be positive, if you assume best of intentions. It’s the “Eat, Pray, Love” culture. Find yourself. Seek your own happiness. It’s okay if you have to hurt your family in the process. They should be happy for you. The kids can still be successful and survive. More people to love. Kids are resilient! And what happens when a kid actually believes it? They are prone to do the same thing to their own families when they are adults. I actually used to say that stuff, because it made me feel good about my family at the time. But how would that have been healthy when embarking on marriage and family as I entered adulthood? I am watching my peers and step siblings make the same mistakes over and over again, as they wander through life confused and in pain. And our culture tells them that anything that feels right and is consensual is healthy. Good feelings may temporarily exist, but it’s not working for them overall.

Thanks for the link, Bryan, and for offering your perspective. I obviously can relate :).

LT-

For me one of the most crucial verses of the New Testament is Matthew 18:7

What this verse gets at, and it’s something that I think most people really have trouble implementing, is that you have to separate between good results of an action and the morality of the action itself. Christians believe that many bad things that happen to us can become beneficial. We can learn from them. We can grow from them. They can make us better people. You get fired, it forces you to think about what really matters, you re-center on your family, then you get a job and now you have better work-life balance. Yay, right?

But that doesn’t mean that someone could be excused for running around trying to get people fired because it might be good for them, right?

So yeah: someone could walk out on their family, come back 10 years later and see that the effect was that their kids had learned to be resilient and had become very, very close and supportive of each other (as siblings) because they valued their family so much after the trauma they went through.

It wouldn’t turn that dad into a hero.

Bad things happening are part of life. They are required to make us into better people. But no one ever gets to use the ability of others to make lemonade out of lemons as an excuse for throwing lemons at people.

As a side note, it drives me absolutely batty when I hear ‘the kids turned out ok in x situation, so x situation is ok.’

I sympathize–I feel this frustration particularly keenly when it’s, “I did x and I turned out okay.” What you can say, though, is that that situation doesn’t preclude success. Many of the arguments about divorce, for example, allege that children of divorce do less well, on average, in a number of measurable and important ways than children of intact two-parent homes. The data we have seem to support that pretty strongly, which is most of what I’ve been hearing about divorce and kids. Even there, comparisons to abusive homes make divorce look like the better option sometimes, is my impression. So my position is twofold: first, without knowledge of what the options were, an outsider is rarely well-placed to determine that the relationship chosen by a particular family was worse than the alternatives. Second, whether a particular type of relationship is bad for kids is measurable–we’ve done it with divorce. So I’m particularly unwilling to excuse claims that a certain type of relationship is bad for children from the need to be tested against data when such a claim is likely to make those children in such a family worse off (also a claim amenable to testing!). Similarly, though many people have the view that all things can turn to good with the grace of God, we still cite aggregate data about divorce.

As for whether there’s a cultural trend toward excusing divorce, a search on “Is divorce bad for a child” was illuminating for me. The Guardian (very left-leaning) and Scientific American are the top two results, unambiguously saying that it is. A little farther down, though, there’s the Huffington Post, with one more reason to hold your face in your hands and lament the demise of journalism. It was hard for me to really understand just how tone-deaf, self-centered, and lacking in empathy people can be when trying to offer comfort to a child of divorced parents. I expect I still don’t fully get it, but if I were a praying man, I’d be asking for some of God’s grace to head over that way for the good of the rest of us.

You wrote, “Between existence in a biologically unrelated (or half-related) family and no existence, it’s hard to make a case that we wrong such a child by selecting the first.” Would you make that argument for a child conceived in rape? In infidelity? Would we argue that those types of conception are good, because the child would not have existed otherwise? One’s existence does not moralize their conception. And I think it is unfair to silence these kids and their struggles by throwing their existence back in their face.

I’m basically willing to say that parents owe children the satisfaction of biological and social needs. The harm done by a rapist seems to me to be done to the victim primarily, and to the child only derivatively because of the virtual certainty that the rapist has not exhibited due care for his (or her) duty to satisfy those needs. I don’t think the harm to a child of rape or infidelity is in the conception as such; if a person conceives a child through infidelity but has a good plan for meeting that child’s biological and social needs, I don’t think the child has a reasonable claim against that parent. That said, when a child is inclined to complain about his or her parenting, I expect this usually has a focus in some failure of parental duties, so rather than silencing him or her, I’d redirect to a more productive line of complaint. But then, I don’t have teenagers yet, so I haven’t had to deal with “Well, I didn’t ask to be born!” as an explanation for ill temper.

Apologies for my failure to correctly use the “cite” tag–not sure what went wrong there.

Amen to that, Nathaniel.

Kelsey, I thought you would find this interesting. It just showed up in my news feed today, so I thought I would share. It is a letter written by a donor-conceived woman. The author runs a site called AnonymousUs.org, which gives a voice to all parties in this process. This is just one of many examples out there, especially now that the first kids are growing into adults.

http://ccgaction.org/uploaded_files/Testimony%20of%20Alana%20S.%20Newman.pdf

Nathaniel’s original post — or maybe one of his earlier comments — pointed out that relationships do not exist in isolation. Divorce is also not this unique situation in its own isolated corner. Science only works when we assume that nature has laws and patterns and that humans also possess a nature. This allows us to draw conclusions about society and relationships without studying every person or every arrangement. Science also requires us to use our intellect, to analyze and connect the dots. I am fine with more tests to gain a more nuanced understanding — truly — but I think we know enough about human nature, biological parents, children, and family structures to draw some solid conclusions about non-traditional relationships and families. We need to start using what we know about things like divorce, adoption, blended families, childhood development, the fertility industry, etc., to apply sound judgment and to help future generations. It might not be politically popular, though.