This is one of those blog posts that, once you’ve read it, makes you wonder how there was ever a possible universe in which you didn’t know the concepts that you just learned: The Heat Death of Humanity: Progressivism as the Second Law of Thermodynamics. The first major new concept has a humble name: paperclipper. According to the Less Wrong Wiki[ref]I have no idea[/ref], the paperclipper is “the canonical thought experiment showing how an artificial general intelligence, even one designed competently and without malice, could ultimately destroy humanity.” Imagine, as the original 2003 paper did, an AI given the task of maximizing the number of paperclips it has in its collection. Seems harmless enough at first glance. However:

If it has been constructed with a roughly human level of general intelligence, the AGI [artificial general intelligence] might collect paperclips, earn money to buy paperclips, or begin to manufacture paperclips. Most importantly, however, it would undergo an intelligence explosion: It would work to improve its own intelligence, where “intelligence” is understood in the sense of optimization power, the ability to maximize a reward/utility function—in this case, the number of paperclips. The AGI would improve its intelligence, not because it values more intelligence in its own right, but because more intelligence would help it achieve its goal of accumulating paperclips. Having increased its intelligence, it would produce more paperclips, and also use its enhanced abilities to further self-improve. Continuing this process, it would undergo an intelligence explosion and reach far-above-human levels. It would innovate better and better techniques to maximize the number of paperclips. At some point, it might convert most of the matter in the solar system into paperclips.

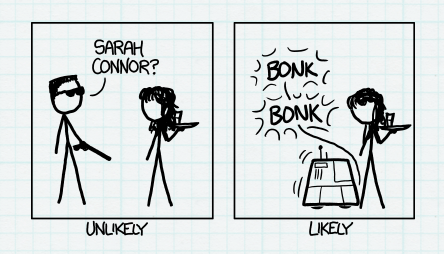

Or, in the words of Eliezer Yudkowsky, “The AI does not hate you, nor does it love you, but you are made out of atoms which it can use for something else.” In this case: paperclips.

Keep that example in mind for a moment, and think about recent critiques of the social justice movement: Chait’s, Ronson’s, or (what the heck), mine. The common thread is that there is no limiting principle to halt the downward spiral of ever increasing levels of outrage over ever smaller indignities. This doesn’t mean that the individual progressive causes are wrong. The problem is that–just as with the paperclipper–a benign (or even good!) goal has been mistaken for the only goal. Justice is the paperclip.

Well, obviously justice is a lot more intrinsically valuable than a paperclip (or any number of paperclips), but the fact remains that it isn’t the only goal. And justice at the expense of truth, or at the expense of mercy and forgiveness, or at the expense of any number of other possible virtues can become just as dangerous as the paperclipper.

There’s more to the story, however. The primary source of energy for the social justice movement is outrage, and the outrage is derived from examples of injustice. The more injustice the movement sees, the more energy it has available. To use a biological metaphor: here you have a bunch of leaf-eating herbivores and along comes an herbivore that can eat entire trees (bark, branches, and even trunks). The new organism is going to out-compete and eventually replace all others. But, in our case, the same feature that makes social justice ideology so perfectly adapted to our memetic ecosystem is also fueling a kind of second law of thermodynamics for social systems.

It seems that perhaps progressivism is the embodiment in human systems of the second law of thermodynamics, which can be roughly stated as “the tendency of natural processes to lead towards spatial homogeneity of matter and energy, and especially of temperature.”

The individual differences that social justice seeks to ameliorate may be, case-by-case, well worth the effort of amelioration. Or even eradication. But without a limiting principle, the risk is that all differences will be eradicated. And that’s bad because”

…If you even care about life existing – let alone the infinite diversity possible therein – then (contra Caplan), boundaries (such as national borders) are an absolute necessity. No differences, no energy flow, no (thermodynamic) work, no life. As in the stars, so on the earth: romance flows from polarity; trade from comparative advantage; thermodynamic work from heat differences;evolution from variation; economic competition from competing alternatives. All progress is driven by differences; so to erase differences is (counter-eponymously) to end progress.

A lot of this is argument-from-metaphor, of course, which is always perilous. But I certainly think there is some validity to this approach.

There are many problems with outrage-fueled progressives, but fear of their uncontrolled growth into the land of The Giver isn’t a reasonable one. It’s an organism that gets weaker as it expands to weirder fringes. I worry as much about world homogenization by an organization that systematically sends out conversion agents both to increase base population and to serve as a sort of chrysalis for the scout pairs.

By ignoring mediating forces like outrage-fatigue and pre-columbian archaeology, these hyperbolic cases become good fodder for sci-fi stories. Luckily the real world doesn’t tolerate monocultures for long.

Agreed. Another example: “oppressed group x needs more rights”. Taken to its logical extreme, this would result in a society in which group x held fascist dictator-esque powers. Since that’s obviously not a goal those concerned with social justice would support, this is really just a roundabout way of asking what the limited principle is. That’s a valid question, which seems to me to be where the validity of this approach comes from. But suggesting that people support something as a way of asking why they don’t seems less direct and more prone to misinterpretation than it could be.

In the social justice realm, this is all the more interesting because it seems to me that a lot of progressives take the question of when we stop to be unripe, even insulting so. Conservatives of my acquaintance generally don’t, and often see the raising of the unripeness concern as a dodge to help disguise their lack of intellectual integrity, because they intend to keep pushing for more rights far beyond the point of equality.

I fear that reasoning from current trends to far-future consequences tends to evoke that sort of accusation. You might get an answer on the limiting principle that way, but I suspect it would be delivered less defensively in response to a clearly abstract question about what priorities can sometimes outweigh equality.

OK, so let me clarify something: this post is not about how the social justice movement is going to lead to a literal dystopia. That’s not really the point I was making at all. To get a legit dystopia in practice (ala North Korea) you need a lot more than a dystopic ideology, and (1) I don’t really see that the social justice movement has those things in place and (2) I’m actually not even that interested in talking about whether or not they do because, frankly, that’s a little silly.

My critique is strictly about the ideology of social justice. And, speaking directly about that ideology, I do find it to be dystopic insofar as it lacks a limiting principle. So I am really not picking an obtuse way of asking: “What is the limiting principle?” I genuinely don’t think that it exists. I could be wrong, of course, but from everything I read the likely end-game of social justice is not coming up against a rational, limiting principle and deciding that the job is done but rather cannibalism and in-fighting hollowing out the movement.

So: no, I don’t think we’re on the verge of a new dystopia. But it’s not because I think that the current social justice movement has a good self-limiting principle. It’s because I think that the radicalization will destroy the movement long, long before it’s time to take any kind of an overt Brave New World / 1984 scenario seriously.

The questions are how much damage the movement will do to our society in the interim between radicalization (in process) and self-destruction, how to ameliorate or repair that damage, and what comes next? The social justice movement (as it exists today) is going to flare out and die long, long, long before social injustice goes away. So: what are alternative models for constructing a better and more just world that don’t share the traits that are leading to social justice’s success today and will lead to its self-immolation tomorrow?

You gentlemen make some very interesting assumptions in regard to how society might play out its desire to ameliorate injustice. Like most things in science (global warming comes to mind) there’s usually other factors we’ve either forgotten or never considered which can turn things at any moment along the line.

Having said that, I really like this article in a broad sense. It brings to light a very real possibility that should be considered. If nothing else it makes you think about how something good, once started, without a defined moment of success,(a stopping point) can lead to unintended disaster.

Consider civil rights and all the steps taken by our society to diminish prejudice. A machine was set in motion which started off creating (paperclips) justice for black people, providing assistance for getting into colleges, jobs, etc. – with the goal of making life for blacks as equal to that of whites as possible. But now it seems as if the mission has been accomplished – for the most part (or course there’s still prejudice out there) but it’s not realistic to think you can eradicate all of it. But, for the most part, people of all races are fairly considered in most dealings in our society at large.

If you were to watch the news – particularly coming from Fergason MO. you’d be under the impression that race relations have never been so bad in this country – when in fact, they’ve never been so good. But, when we have a segment of our society allowed to believe that white policemen can honestly get away with shooting and killing perfectly innocent black kids – there’s a problem!! – and it isn’t racism in its traditional sense.

To my way of thinking, we accomplished our original goal, but we failed to shut off the paperclip-making machines. We have individuals and industries dependent upon race animosity, and if it doesn’t exist, then they are obligated to create it, gin it up, and keep it going. Where will it lead? Too many paperclips are indeed dangerous – and perhaps worse than not having paperclips at all.

In any case, your analogy has some actual living proof to it in the real world today.

Great article!

Nathaniel, I think you’re right that the social justice movement (to the extent that’s a thing) as such has no limiting principle. My assumption is that this is because there’s a broad coalition of people who think that movement on various social justice issues will improve things, but they do not agree on limiting principles. But that’s really just another way of putting Ryan’s original point–as progress proceeds, different members of that coalition will peel off as their limiting principles are reached.

It seems to me analogous to the suggestion that advocates for smaller government are effectively anarchists. Since different small-government folks have different limiting principles on the minimum size of government, small-governmentalism as such lacks a limiting principle. I’m not sure that has any interesting consequences. Certainly I’d expect that any given thoughtful advocate of a smaller government would be able to explain their limiting principle, just as I’d expect any thoughtful advocate for a particular issue of social justice to have one. I certainly do.

Mark, thank you for illustrating why the question about limiting principles can shade into insult. Black people in America are much more likely than whites to have their families broken, to be unemployed, to suffer police brutality, and to be poor. If you think that none of these matter enough to be worth addressing, what’s on the other side of that ledger which is more important than family, work, bodily integrity, and wealth?

The social justice movement’s lack of a shared limiting principle is hardly unique. Few organizations or organisms self-regulate, but instead rely on outside forces to constrain overgrowth. Kelsey notes that the social justice movement is moderated by the self-regulation of the individuals that comprise it, just like any political party or rights-advocating organization. I just think it’s misleading to single out social justice as a limitless wildfire when the same can be said of almost any gathering of organisms.

As for Nathaniel’s second question, “what are alternative models for constructing a better and more just world that don’t share the traits that are leading to social justice’s success today and will lead to its self-immolation tomorrow?”

The same way you quell the fire of any angry group: Involve them in the political process. eg: Northern Ireland or South Africa. Imperfect, but better than some of the examples Mark discussed.

I don’t think that the social justice movement is absolutely unique in the absence of a limiting principle. But it’s not just business-as-usual either.

Kelsey’s example of small-government conservatives is a pretty good example. There is not one organization or institution behind small-government conservatism, but it does have a number of limiting principles that are fairly universal, such as the near-worship of the US Constitution and the hagiographic view of the Founding Fathers. You can’t get from “small government” to “no government” because of those corollaries. So, while the movement may be more radical than is reasonable, it does have a very clear and strong limiting principle that is widespread.

The social justice movement doesn’t have such a principle.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m not saying that anything goes, and that social justice advocates are just a hair’s breadth from starting up re-education camps for those who don’t join the bandwagon (if they had the power to do so, which of course they don’t.) Social justice advocates are not prone to go vigilante and start methodically assassinating opponents either. There are lots of constraints on what a social justice advocate will do.

But what I am saying is that there is really a very unusual combination of factors that make the ideology at the heart of social justice unusually unlimited. (Not uniquely, necessarily.)

A small government conservative stops when they hit the Constitution (more or less). That’s not a constraint on the means of small-government conservatism. That’s a constraint on the end itself.

Where’s the constraint on social justice advocacy? At what point does a social justice advocate say that not only are the means constrained, but that the end itself needs to be limited? That enough justice is enough?

See, it doesn’t even make sense to really ask that question. Any injustice is bad, right? And, furthermore, any difference can be conceptualized as an injustice? Therefore, social justice advocacy is really unlimited in a particular way that is not universal.

People claiming to be small government conservatives brought us the Patriot Act. Their near-worship of the US Constitution apparently doesn’t extend to the 4th, 6th, 7th, or 8th amendments. Small government conservatives are pushing voter ID laws that violate the 24th amendment. Small government conservatives on the Alabama supreme court are openly violating the constitution even now, denying marriage rights. Small government, to some, includes posting the ten commandments in government buildings and starting public meetings by ignoring the separation of church and state. Government would be smaller without prayer, or making people pay to vote, or torture.

Small government conservatives are clearly better than social justice-ers at staying in the lines they publicly set. They have better foundational infrastructure and discipline. Every organization and organism will inevitably try to wriggle free of its limits, but it’s harder to bend your rules when they were written by Jefferson. (Not impossible, clearly.)

I don’t want to turn this into a political debate. It’s just silly to claim that everyone who claims to be a small government conservative is a paragon of principle toeing the line like a Victorian at a duel.

So, yes, they are more limited by principles than this quasi-Cultural Revolution, but lets not go nuts.

Ryan-

Conservatism has, for the last couple of decades, been a coalition that includes foreign policy conservatives (hawks), social conservatives (traditionalists), and free market / libertarians (small government conservatives). It was the hawks, and to a lesser extent the traditionalists, that were behind the Patriot Act. It had absolutely zero to do with small government.

So yeah: small government ideology dose have a limiting principle. I’m not arguing that it’s perfectly adhered to. I’m just saying that when you look at the ideology, it has self-contained limits. Social justice advocacy lacks those limits, and has a unique predisposition towards radicalism.

Look, this isn’t conservative vs. liberal. There are lots of strains of liberalism that aren’t social justice advocacy just like their are lots of strains within conservatism that aren’t small government conservatism.