Last year, The Atlantic reported on a study that offered a plausible definition of “cool.” “Cool,” The Atlantic said,

Last year, The Atlantic reported on a study that offered a plausible definition of “cool.” “Cool,” The Atlantic said,

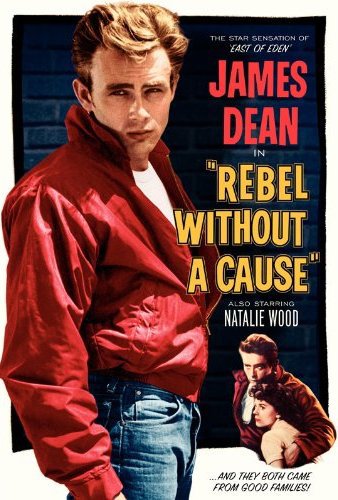

means departing from norms that we consider unnecessary, illegitimate, or repressive—but also doing so in ways that are bounded. The 1984 Apple ad that said, essentially, “you have a choice; don’t buy IBM!” was considered one of the coolest commercials of all time, because it was, in the researchers words, “autonomous in an appropriate way.” But a 1984 Apple ad saying “you have a choice; don’t pay federal income taxes!” wouldn’t be cool, because taxes are legitimate; and a 1984 Apple ad saying “burn IBM’s headquarters to the ground!” wouldn’t be cool, because that’s just overdoing it. Cool requires a bit of Goldilocks. It also requires something worth rebelling against.

The magazine recently interviewed a pair of neuroscientists on the same topic. “Cool,” according to these researchers, emerged in the 1950s. “Why were people getting so rebellious during one of the greatest periods of economic expansion in our history?” they ask. They conclude that it was because “the competition for the limited status of a traditional social hierarchy was getting too intense. It was the right conditions for the rebel instinct to ignite, and it started to drive consumption through rejecting the traditional routes to status and creating cool new lifestyles.” Cool, as the article name makes explicit, was created by capitalism and growing consumerism.

However, one of the most interesting parts of the interview was the list of four “damaging” myths about consumerism:

1. “It doesn’t make us happy.”

In 1974, Richard Easterlin reported that although richer people were happier than poorer people in the same country, people in wealthier countries were no happier than those in poorer ones. The implication was that happiness depended on relative income—how we stack up against the proverbial Joneses. But new studies question whether there ever was an Easterlin Paradox: The people of sub-Saharan Africa are not as satisfied with their lives as people in India, who are not as satisfied with their lives as the people of France or Denmark. There’s a global relationship between income and life satisfaction that shows no sign of a satiation point.

2. “It relies on instilling false needs in us because it’s contrary to our real nature.”

Our research show why the second myth is false. By examining how the brain responds to “cool” products, we discovered that they help fulfill a basic human need: to be recognized and respected by others. Our brains contain what’s basically a “social calculator” that keeps track of how we think other people are thinking about us—we feel its results as social emotions like pride and shame. Today, it’s typically called “social status,” but that has lingering negative connotations. We found that products are basically extensions of ourselves that reflect who we are—we use them to bond with others who share the same values. Doing this successfully was key to survival throughout human evolutionary history—you really needed allies, friends, and partners to survive.

3. “It erodes public life.”

There are lots of ways to gain status—it’s what even drives some Westerners to join ISIS—but integrating our need for status into the economy was, in our opinion, an enormously important feat. It allows the ways to gain status to expand over time, and it shows why the third myth is false—we use products to create lifestyles and community.

4. “It’s primarily about “stuff.””

Consumerism isn’t just about materialism. We use products socially—music is a great example. Look at all the lifestyles arranged around various musical tastes.

Check out the whole interview.