So the BBC has an article that is probably not going to generate a ton of sympathy with anyone: The surprising downsides of being drop dead gorgeous. It’s actually a pretty great article for a serious discussion about privilege, however, because it has attributes of identity privilege (your looks are largely intrinsic and immutable, like your race or gender) but with less (not none, but less) emotional volatility.

The obvious takeaway is that being pretty is basically a good thing:

In education, for instance, Walker and Frevert found a wealth of research showing that better looking students, at school and university, tend to be judged by teachers as being more competent and intelligent – and that was reflected in the grades they gave them.

But one of the interesting things is that this privilege isn’t always beneficial. There are times and places where being pretty isn’t going to work to your advantage. And these aren’t weird, idiosyncratic hypotheticals. These are real-world situations that we all face:

And as you might expect, good-looking people of both genders run into jealousy – one study found that if you are interviewed by someone of the same sex, they may be less likely to recruit you if they judge that you are more attractive than they are.

Here’s another one:

More worryingly, being beautiful or handsome could harm your medical care. We tend to link good looks to health, meaning that illnesses are often taken less seriously when they affect the good-looking. When treating people for pain, for instance, doctors tend to take less care over the more attractive people.

That one is particularly interesting, because the mechanism is identical to a lot of the benefits of beauty. People associate beauty with health, high-functioning, etc. Usually this is good. When you’re beautiful and in pain, however, this exact same mechanism turns against you.

And another one:

And the bubble of beauty can be a somewhat lonely place. One study in 1975, for instance, found that people tend to move further away from a beautiful woman on the pathway – perhaps as a mark of respect, but still making interaction more distant. “Attractiveness can convey more power over visible space – but that in turn can make others feel they can’t approach that person,” says Frevert. Interestingly, the online dating website OKCupid recently reported that people with the most flawlessly beautiful profile pictures are less likely to find dates than those with quirkier, less perfect pics – perhaps because the prospective dates are less intimidated.

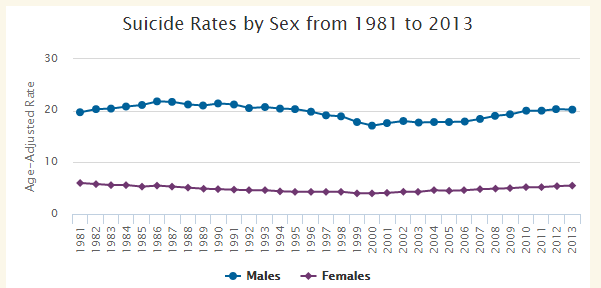

This one is interesting, because it shows that the benefits of privilege can entail their own costs. Is it possible, for example, that there’s a connection between the privilege enjoyed by white males and the fact that they have the highest risk of suicide, and often at the peak of their socio-economic power?

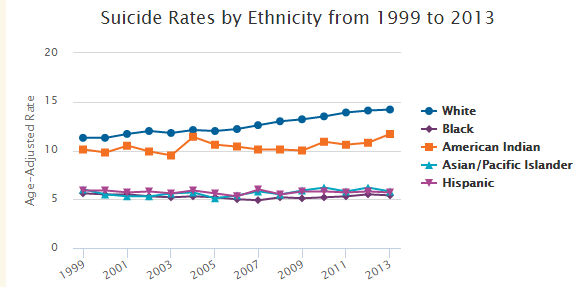

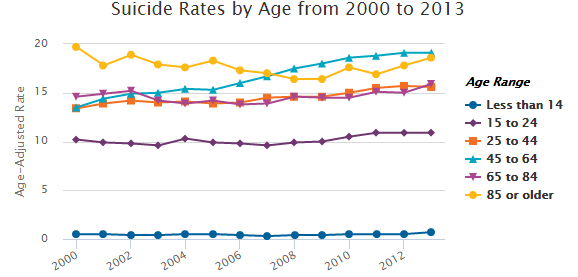

Obviously it’s not as simple as “loneliness of being privileged = high suicide rate.” That wouldn’t explain the very high rate of suicide among American Indians nor the fact that the age group almost as likely to commit suicide as the 45-64 (when white men are typically at the height of their social power) is 85+ (when white men are generally frail and socially vulnerable). But that’s kind of my point: privilege isn’t that simple It’s not just a matter of “this attribute makes your life easier,” whether the attribute is being white or being beautiful.

This also isn’t some kind of appeal to sympathy. As I said at the outset: I hardly doubt that anyone is going to suddenly feel bad for natural born beauties. So this can hardly be construed as an argument that really it’s the white male who has it hardest of all. That’s not my point. My point is simply that privilege–even when we’re talking about identity-based privilege–is more complex and more interesting than the dominant rhetoric allows.