This opinion piece from the New York Times popped up in my feed a couple of weeks ago: Why Our Children Don’t Think There Are Moral Facts by Justin P. McBrayer. It’s a pretty common sub-topic within the “kids these days” genre and it goes something like this. First, kids these days are taught that morality is subjective (often as a side-effect of misguided tolerance or non-judgmentalism efforts):

What would you say if you found out that our public schools were teaching children that it is not true that it’s wrong to kill people for fun or cheat on tests? Would you be surprised?

Second, this moral relativism leads to high rates of immoral behavior among students (e.g. cheating):

It should not be a surprise that there is rampant cheating on college campuses: If we’ve taught our students for 12 years that there is no fact of the matter as to whether cheating is wrong, we can’t very well blame them for doing so later on.

I don’t know that there’s any direct evidence of this. For example, I don’t know of any survey that specifically asks about cheating behavior and asks about moral relativism, which would be interesting. But the link seems plausible.

McBrayer then points out that, among philosophers, moral relativism is rare:

There are historical examples of philosophers who endorse a kind of moral relativism, dating back at least to Protagoras who declared that “man is the measure of all things,” and several who deny that there are any moral facts whatsoever. But such creatures are rare.

I was interested, so I dug around and found a survey that asked philosophers about that explicitly. Here are the results:

Accept or lean toward: moral realism 525 / 931 (56.4%)

Accept or lean toward: moral anti-realism 258 / 931 (27.7%)

Other 148 / 931 (15.9%)

I’m not sure that almost a quarter of philosophers accepting moral relativism makes it “rare,” but it is certainly the case that they are outnumbered more than 2:1 by philosophers who accept moral realism. That’s really interesting me for a couple of reasons. First, conservatives often blame liberal trends among college kids on the overwhelmingly liberal atmosphere of college campuses, but at least in this regard the students are clearly way out in front of the professors (and heading in the opposite direction). Second, in popular discussion I usually see moral objectivism / moral realism associated with simplistic religious beliefs and therefore looked down on by the cool kids of the Internet who are all convinced that evolution explains morality and therefore morality is socially constructed and relative. Newsflash: moral realism is not just for Young Earth Creationists.

McBrayer also points out that indoctrinating our kids to believe moral relativism starts early:

When I went to visit my son’s second grade open house, I found a troubling pair of signs hanging over the bulletin board. They read:

Fact: Something that is true about a subject and can be tested or proven.

Opinion: What someone thinks, feels, or believes.

As McBrayer points out, this is a total train wreck that conflates three distinct concepts: true vs. false, objective vs. subjective, and knowable vs. unknowable. Ontology, epistemology, and relativism are all mashed together. What about things that a person thinks that are factual and can be proven? What about statements that are objectively false but also unprovable?

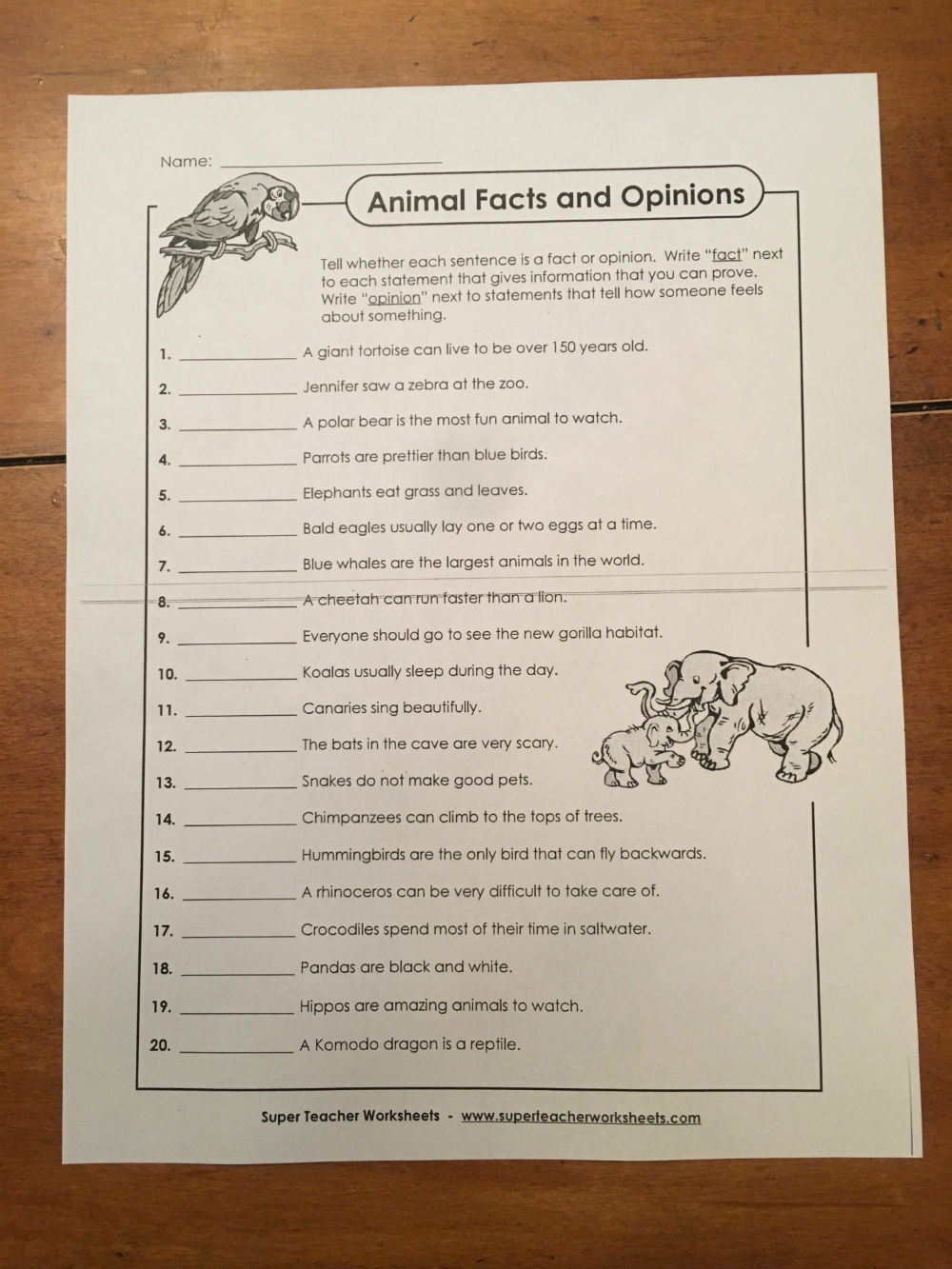

Coincidentally, within day or two of reading this, my son came home with the following homework:

It’s not quite as bad as McBrayer’s example, but it’s not good either.

I’m not really sure who to blame on this one, but it’s just another reason I try to keep a fairly close eye on what my kids get taught at school. Teaching is hard, and my kids have great teachers this year, but it’s important to let ’em know from time to time that the stuff they are taught in school has to be taken with a grain of salt.

I’d there any evidence they’re being taught to embrace moral relativism, as opposed to just being taught about it? I doubt kids are taught cheating is OK, for example.

Ryan-

I’d there any evidence they’re being taught to embrace moral relativism, as opposed to just being taught about it?

Just look at the statements that McBrayer quoted:

Fact: Something that is true about a subject and can be tested or proven.

Opinion: What someone thinks, feels, or believes.

Can “cheating is wrong” be “tested or proven”? No, it cannot. So the statements–which the kids are taught (rather than “taught about”) logically entail moral relativism.

Whether or not kids actually draw the implication is up for consideration. (I can’t imagine how they could not draw the implication over the course of many years.) Even moreso is whether–having been taught moral relativism–this converts to immoral behavior. Those are the open questions.

Well, “cheating is wrong” isn’t a fact, so that’s why they’re teaching that. “Everything breaks down when people cheat” is a fact, which they could easily teach. Teaching “moral facts” is for people who’d rather not teach the potential harm. Discouraging kids from asking “why” is probably the last thing schools should be doing. Teaching compelling reasons for our rules is a far more useful education.

Obviously there’s nothing wrong with telling kids they shouldn’t cheat on tests, or that it’s not ok to kill people for fun (the ridiculous example that leads this post.) These are obvious conclusions easily communicated, but aren’t facts.

As someone who spent time as an academic philosopher who was both atheist and a moral realist, this doesn’t really bother me. It’s very common for virtually everyone to have some concepts that aren’t that well-founded but are still useful. The people involved in making individual homework assignments are generally not philosophers, so you’d expect their thinking on most of what they teach to be relatively superficial, and there’s no practical alternative while teaching is done mostly directly by humans.

All of that aside, I have to admit that the teacher seems to have gotten some things right which McBrayer doesn’t. For example, “Copying homework assignments is wrong” is context-dependent. For handwriting homework, for example, it’s fine. There might well be cultures in which homework plays a role which is not undermined by copying, or in which copying homework is an important move in an accepted social negotiation. It doesn’t universally violate the norms of one’s culture, and the wrongness of copying homework is basically never independent of cultural norms. McBrayer is right that there’s some fuzziness about what constitutes opinion (in this case, the fudging of context-dependent vs. universal into the fact vs. opinion mold), but so what? Simplified concepts which we deploy over-broadly in order to have some concepts to bring to bear on various situations are endemic to education, and I’m not sure how it would be possible to avoid them in a developmentally-appropriate way.

I also think there’s a way out of the entailment of moral relativism, but I admit it’s too subtle for most students to be likely to entertain it themselves. But I think it’s correctable if you prompt kids to think about whether definitions are facts or opinions, and how the simplistic fact vs. opinion dichotomy sort of imports that on both sides.

Ryan-

Suffice it to say, I’m not surprised to find that you are a moral relativist. The attempt to reduce morality to some kind of amoral criteria is something of trademark of the engineering / technology set. I think it’s depressing and philosophically vapid, but it’s certainly widespread.

Of course, that’s empirically false, for starters. The reality is that most people do cheat. They simply constrain their cheating to fairly small amounts that they can rationalize / get away with. Notably, “everything does not break down” when this happens since, after all, it’s the present state of affairs. (Much of this research is summarized by Dan Ariely, Jonathan Haidt, and similar researchers.)

More to the point, however, it begs the question of Why?. Which is what–in practice–all attempts to collapse morality into evolutionary patterns, enlightened self-interest, the communal welfare, etc. end up doing in the end.

The sad irony is that popular moral relativism–a bankrupt and incoherent perspective–is successfully precisely because of the extent to which we’re all moral objectivists at heart. We have certain values–vaguely described as “do no harm” and “greatest good for the greatest number” and so forth–so deeply engrained that when we found ersatz moral relativism on these principles we are able to close our eyes and pretend that we’re not actually doing precisely what we’re doing: appealing to objective morality.

Obviously there’s nothing wrong with telling kids they shouldn’t cheat on tests, or that it’s not ok to kill people for fun (the ridiculous example that leads this post.) These are obvious conclusions easily communicated, but aren’t facts.

In what sense is it obvious that it’s not ok to kill people if that is not a fact? I am curious to know how a thing can be obviously true while at the same time not factual.

Either the truth of a moral claim exists outside any particular perspective (this is moral realism / moral objectivism) in which case it is possible to say that it is obviously wrong to kill other people, or the truth of a moral claim depends on a particular perspective (this is moral subjectivism / moral relativism) in which case the most that you can ever hope to say is that killing other people seems wrong to quite a lot of people. Which is an observation about popularity and taste. It is precisely the same kind of statement as “tomatoes taste good” or “vanilla is tastier than chocolate.” In other words, it’s a statement that doesn’t carry any kind of normative or prescriptive weight at all and is thus, not actually moral at all.

Kelsey-

I’m not convinced that any of this indicates the sky is falling, either, but I do think two things are plausible:

1. Moral relativism is increasingly prevalent in rising generations

2. It has a negative impact on moral behavior

If those are true, then this is a good hypothesis that may explain part of the trend. But I present it purely as that: a promising hypothesis for a much-observed but not empirically validated (that I know of) phenomenon. It’s by no means open-and-shut, and the question “Are the kids alright?” is one that deserves a lot of skepticism since every generation is convinced the following generations are going to hell in a handbasket, and so far we don’t seem to have arrived in a fiery inferno.

On the other hand, I’m not quite as blase as you, either.

there’s no practical alternative while teaching is done mostly directly by human

I remember being taught as a kid that factual statements are statements that can be proven incorrect or proven correct. This isn’t quite right either (since it blends epistemology and ontology) but it is much, much better than the example McBrayer presents. The idea of something being factually wrong is rather vital, don’t you think?

I think it’s possible to teach the basics in an age-appropriate way. All that needs to be done is to differentiate between:

1. Things that are objectively true or false and verifiable (factual)

2. Things that are objectively true or false but not verifiable (factual)

3. Things that are subjective (opinion)

There are plenty of examples you can come up with for each category for kids of this age (7, in the case of my son).

All of that aside, I have to admit that the teacher seems to have gotten some things right which McBrayer doesn’t.

This is why no one likes professional philosophers! :-P Clearly there is a difference between:

A – There is no objective moral principle relevant to a question of cheating (McBrayer’s target)

B – There are exceptional cases (irrelevant)

So yeah, you can find exceptions to McBrayer’s simplistic statement, but if the exceptions don’t actually speak to the question of objectivism / subjectivism then we’re just kind of off in the weeds for no point whatsoever.

Nathaniel- Are you in a bad mood? You aren’t usually this grouchy.

I think we can agree that the mass of an electron, “cheating is wrong”, and “man shall not lie with man; it is an abomination” are different categories of claims. To lump them all under the heading of “facts” is misleading in that it implies they are the same type of thing.

So us philosophically vapid, technological types prefer to restrict the title of “facts” to things that really are nigh-indisputable.

“In what sense is it obvious that it’s not ok to kill people if that is not a fact? I am curious to know how a thing can be obviously true while at the same time not factual.”

Because the care/harm foundation is obvious to most vertibrates, even if they have to weigh the caring for their own empty stomachs against the harm to another animal.

“the most that you can ever hope to say is that killing other people seems wrong to quite a lot of people. Which is an observation about popularity and taste. It is precisely the same kind of statement as “tomatoes taste good” or “vanilla is tastier than chocolate.””

This is an example of a slippery slope fallacy.

Nathaniel- Are you in a bad mood? You aren’t usually this grouchy.

Yes, I am.

Sorry.

:-(

The problem (other than me being grumpy) is a conflation of two distinct concepts: epistemology (how do we know the answer to a question?) vs. subjectivity / objectivity (where does the answer to a question reside?).

For example, “nigh-indisputable” and “obvious” are both descriptions of certainty. But they don’t speak to the subjectivity/objectivity distinction.

So you might say the care/harm distinction is obvious, but that still leaves open the question: is it objectively true that causing unnecessary harm is bad? Or subjectively true? If it is objectively true, than that’s where McBrayer’s criticism comes into play. And honestly, I’m not sure: do you think morality is objective or subjective?

This is an example of a slippery slope fallacy.

Same thing here. It’s not about slippery slopes. That would be a question of degree. It’s about categories. If morality is subjective, then the truth of a moral claim ultimately resides in a specific person’s perspective and there can be no other recourse. In that case, the statement “killing other people is wrong” is just an expression of a particular viewpoint. It is the same kind of statement as “tomatoes taste good.” You can’t really argue if tomatoes taste good or not. To some people, they do. And that is just a fact about their perceptions. And to other people they do not, and that is just a fact about their perceptions. That is the definition of subjectivity: the truth claim gets to a person’s perspective and it ends there.

It seems to me that you’d want a hierarchy that looked something like this:

Fact – Something is objective and it is easily verifiable. Notice: that’s two different kinds of criteria.

?1 – Something that is objective and not easily verifiable. This would be a statement like, “there is a grand, unifying theorem.” It’s certainly true or false (thus: objective) but we don’t actually know.

Opinion – Something that is subjective. This would be something like “Tomatoes taste good” or “killing is wrong.” These are really the same kind of statement if morality is relative.

Notice: there aren’t two versions of the opinion, one that is easy to verify and one that is hard. That is because “verifiable” doesn’t apply to subjective statements. To verify is to corroborate with an external benchmark, but subjective claims don’t care about external benchmarks.

I don’t really have a problem if you want to reserve “fact” for just claims that are objective AND easy to verify. What I do find troubling is when there is a collapse of distinct issues: verifiability and objectivity, such as McBrayer points out in his examples.