In honor of former World Bank economist Branko Milanovic’s[ref]Nathaniel and I used some of Milanovic’s work in our SquareTwo article.[/ref] new book Global Inequality: A New Approach for the Age of Globalization (out this month),[ref]You can find The Economist‘s review of the book here.[/ref] here is a NYT piece on his previous book The Haves and Have-Nots:

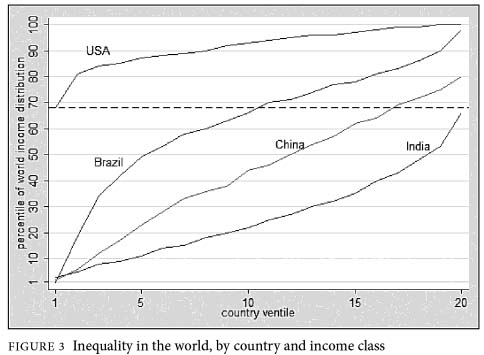

The graph shows inequality within a country, in the context of inequality around the world. It can take a few minutes to get your bearings with this chart, but trust me, it’s worth it.

Here the population of each country is divided into 20 equally-sized income groups, ranked by their household per-capita income. These are called “ventiles,” as you can see on the horizontal axis, and each “ventile” translates to a cluster of five percentiles.

The household income numbers are all converted into international dollars adjusted for equal purchasing power, since the cost of goods varies from country to country. In other words, the chart adjusts for the cost of living in different countries, so we are looking at consistent living standards worldwide.

Now on the vertical axis, you can see where any given ventile from any country falls when compared to the entire population of the world.

Now the clincher:

Now take a look at America.

Notice how the entire line for the United States resides in the top portion of the graph? That’s because the entire country is relatively rich. In fact, America’s bottom ventile is still richer than most of the world: That is, the typical person in the bottom 5 percent of the American income distribution is still richer than 68 percent of the world’s inhabitants.

Now check out the line for India. India’s poorest ventile corresponds with the 4th poorest percentile worldwide. And its richest? The 68th percentile. Yes, that’s right: America’s poorest are, as a group, about as rich as India’s richest.

This goes hand-in-hand with yesterday’s post about GDP per capita (PPP). Should provide some much-needed context when we talk about inequality and “the rich.”

Yes, very interesting graph and article, thanks for posting it.

To continue trying to play a bit of the loyal-opposition role here, I think particular implications of this graph are literally unbelievable. That is, I think economists are often prone to view these kinds of graphs as stronger indicators of happiness and well-being–after all, happiness and well-being are positively correlated with income–than is warranted.

That is, my interaction with the poor in the U.S. vs. the relatively affluent (median income in the country where they were living, or above) in other countries (esp. Russia, because of my mission there) suggests a rather different story. My own (admittedly very subjective) sense is that the relatively affluent in other countries are much, much happier and better off (in the well-being sense that I think philosophers and social scientists ultimately have in mind) than the poor in the U.S.

The reason, I would say this is primarily because I think the poor in the U.S. experience a high degree of social, emotional, and psychological stress in comparison to the lack of such stress among the relatively rich in other countries. The relatively rich have higher social status and a sense of accomplishment that is contributes significantly to happiness and wellbeing in non-economic ways, it seems to me. And I think they experience much less stress in the sense of worrying about having enough money to pay basic bills, having enough time to take care of basic kids’ needs, etc.–of course there are other kinds of work-related stress they experience, but I’d argue it’s on a very, very different level.

Anyway, if nothing else, I think it’s important to acknowledge that these other non-economic factors and issues are very important to acknowledge, consider, and some try to take into account, even if the underlying thrust of your argument (that we should worry more about how poor the poor are and spend less effort griping about how rich the rich are, as I read you) remains intact.