A Facebook friend shared a link to Clay Shirky’s Medium post (There’s No Such Thing As A Protest Vote) and tagged me. I had thoughts, and so I thought I’d share them.

I’m not sure if Shirky’s slapshot case is meant as a serious argument or merely a pretext for a rant. This paragraph, which comes towards the end when the tone shifts abruptly from reasoned to strident, highlights my confusion:[ref]Never go full rant[/ref]

Throwing away your vote on a message no one will hear, and which will change no outcome, is sometimes presented as ‘voting your conscience’, but that’s got it exactly backwards; your conscience is what keeps you from doing things that feel good to you but hurt other people. Citizens who vote for third-party candidates, write-in candidates, or nobody aren’t voting their conscience, they are voting their ego, unable to accept that a system they find personally disheartening actually applies to them.

Nevertheless, the first 1,000 words present a case, and so we’ll take it on the merits. But first, let us simply observe that accusations of disloyalty are Plan A when it comes to browbeating recalcitrant idealists into conformity.That’s not to say there’s never truth to the idea that we should sometimes put our personal preferences aside for the sake of a group’s welfare. It is to say that deploying the exact logic under which despotic regimes have justified silencing voices of protest throughout history ought to be treated as a red flag. Besides which, there’s a big difference between issues of personal taste and issues of conscience. That’s something we’ll return to in the end.

Shirky’s argument about protest votes boil down to two claims. First, it’s a “message no one will hear” and second, it “will change no outcome.” Both these claims are false.

When it comes to “no one will hear,” Shirky argues that since it doesn’t change the outcome of the vote, not voting and voting for a third-party candidate are equivalent. His argument seems to be that, since we can’t guess why a voter would pick Gary Johnson or Jill Stein or to abstain altogether, no information is transmitted. But if no information is transmitted, then we ought to be able to say absolutely nothing whatsoever about the differences in political preference between a group of Gary Johnson voters, a group of Jill Stein voters, and a group of non-voters. But we can infer all kinds of things about the preferences of these groups from the votes they cast. What’s more, if we can’t derive why they voted from the who they voted for, then that applies to voters who pick Hillary Clinton or Donald Trump as well. If we can’t say anything about third-party voters or non-voters based on their votes (or lack thereof), then we can’t say anything about anybody based on voting behavior.

On the other hand, maybe Shirky isn’t saying that it’s impossible to derive the why from the who, but just that nobody will take the trouble to do the derivation: “But it doesn’t matter what message you think you are sending, because no one will receive it. No one is listening.” This approach doesn’t fly either. As Shirky points out, in a parliamentary system the coalition-building happens after the votes are cast when various small, relatively ideologically pure parties have to form a coalition to govern. In a 2-party, winner-take-all system the coalition-building happens before the votes are cast, with the Republican and Democratic parties pulling together various constituencies to form coalitions. But how does he think that this happens if the respective parties don’t pay very careful attention to what they can infer about voters from every source available, including third-party votes? It is emphatically not the case that “no one is listening.” We have an entire industry of pollsters, analysts, and consultants who make a living by listening to the signals that voters send, and a protest vote is a pretty clear signal.

It’s easy to see how the argument that protest votes “will change no outcome,” falls immediately after the argument that they are a “message no one will hear.” The Democratic and Republican parties are not going to spend millions and millions of dollars every year on small armies of pollsters, analysts, and consultants to infer voter preferences for the purpose of crafting their coalition and then just ignore the results.

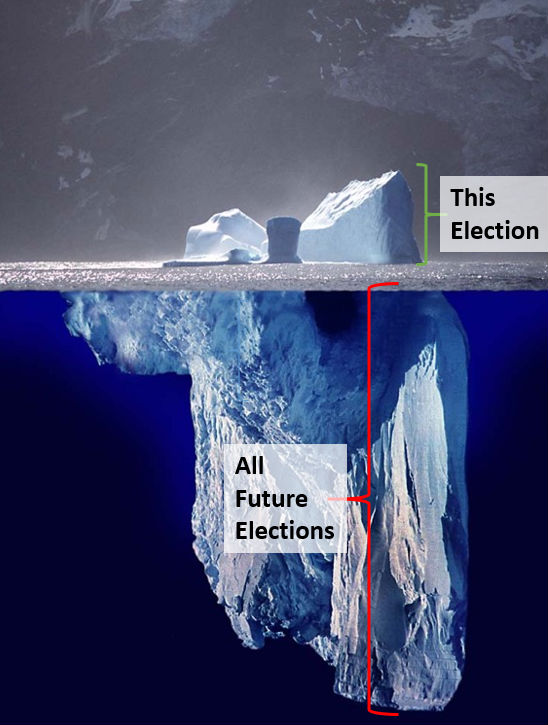

If literally the only thing that you are willing to consider is the result of one, particular election then–and only then–does it make sense to say that protest votes are indistinguishable from non-voting and therefore don’t exist. But pretending those future elections don’t exist doesn’t actually mean that they don’t.

If you want to change the behavior of one of the two major parties, then the best way to do it is not to stay home, but rather to vote for someone else. If you would like to change one of the two major parties to be more like the other one, than by all means switch from R to D or from D to R. In that case, protest votes don’t enter into it. But if you wan to move either (or both) of the major parties in a direction neither is amenable to, then the best and clearest way to send that signal is through a third party.

Of course, there is a cost associated with that. The protest vote is going to have no impact on today’s election and only a possible impact on future elections. And so the most reasonable theory of protest voting is to attempt to weigh the benefit of sending a corrective signal for the future against the cost of not influencing an election in the present. This is a very, very difficult calculation to make and the stakes are high. That is why reasonable people can come to differing conclusions, even when their political views are quite similar.

Notably, however, the simplest and most straight-forward explanation of protest voting is omitted from Shirky’s piece, which posits only three options: boycott, defection, or “step to third-party victory.” Each of these options has some validity to it, but none of them are as potent or as simple as the one given here. Most tellingly: none of them incorporate Shirky’s own analysis of the incentives of coalition-building in a 2-party system. Defection is closest to what I have in mind, but Shirky explains it only in terms of simplistic: “voters believe they can force a loss on either the Democrats or the Republicans, and thus make that party adopt their preferred policies, rather than face another such loss in the future.”

It is neither necessary nor possible for protest votes to “force a loss.” It is not possible for the simple reason that–like any complex event–there is never one, singular explanation for the outcome of a vote. It is not necessary because the two major parties are in constant competition with each other to build the bigger coalition. Protest voters do not need to threaten or coerce them–although that might help–but only to clearly communicate what they want.

One major thing to keep in mind: the entire point of having an election is that we don’t know ahead of time what people want. If we had perfect knowledge of preferences, we wouldn’t need to vote.[ref]We would still need a system for integrating those preferences into laws and policies and government actions, but that doesn’t require elections.[/ref] Ergo, the parties don’t actually know–with perfect precision–what constituencies exist out there and how best to appeal to them. Protest votes are an extreme form of conveying that information, and that is a much lower bar than the idea of having to “force a loss.”

Finally, the reactions to protest vote are going to be subtle, temporally distant, and often intentionally muted. They will be subtle because a major party is a coalition: a delicate balance of overlapping constituencies. They do not, with rare and historical exceptions, make abrupt changes in any direction because it threatens the cohesiveness of the overall balance. They will be temporally distant because the very earliest that a party can visibly react is the next election, a minimum of two years away, and in practical terms the lag will be even greater.[ref]It’s not like parties have the power to arbitrarily swap out candidates on a whim based on the most up-to-date information.[/ref] And they will often be intentionally muted because part of the narrative every party tries to present is that it’s always been right, and so changes–especially in reaction to third-party protest votes–will be deliberately downplayed in front of most audiences.

But the fact that the impact of protest votes is not easy to spot doesn’t mean that they don’t exist. To believe that, you’d have to believe either that protest votes convey no useful information about voter preferences or that Democrats and Republicans ignore useful information about voter preferences, neither of which is tenable.

Shirky’s argument is very hard to take seriously on its merits, since it requires us to ignore obviously relevant factors (like future elections) and accept flagrantly false premises (like the idea that protest votes either convey no useful information or that major political parties don’t care about that information). However, it does provide an approximately thousand-word pretext for the real payload of this article, which consists of claims like these:

- Advocates of wasted votes don’t bring up this record of universal failure, because their votes aren’t about changing political results. They’re about salving wounded pride.

- Citizens who vote for third-party candidates, write-in candidates, or nobody aren’t voting their conscience, they are voting their ego…

- The people advocating protest votes believe they deserve a choice that aligns closely with their political preferences.

This makes this whole piece an example of bulverism, a coin terms by C. S. Lewis.

You must show that a man is wrong before you start explaining why he is wrong. The modern method is to assume without discussion that he is wrong and then distract his attention from this (the only real issue) by busily explaining how he became so silly.[ref]I got the quote from Wikipedia, which has the original source.[/ref]

Another explanation of how bulverism works shows how it relates in this case:

Suppose I think, after doing my accounts, that I have a large balance at the bank. And suppose you want to find out whether this belief of mine is “wishful thinking.” You can never come to any conclusion by examining my psychological condition. Your only chance of finding out is to sit down and work through the sum yourself. When you have checked my figures, then, and then only, will you know whether I have that balance or not. If you find my arithmetic correct, then no amount of vapouring about my psychological condition can be anything but a waste of time. If you find my arithmetic wrong, then it may be relevant to explain psychologically how I came to be so bad at my arithmetic, and the doctrine of the concealed wish will become relevant — but only after you have yourself done the sum and discovered me to be wrong on purely arithmetical grounds. It is the same with all thinking and all systems of thought. If you try to find out which are tainted by speculating about the wishes of the thinkers, you are merely making a fool of yourself. You must first find out on purely logical grounds which of them do, in fact, break down as arguments. Afterwards, if you like, go on and discover the psychological causes of the error.[ref]Again, my immediate source is Wikipedia.[/ref]

I’ve also seen this general tactic referred to as “the heuristic of suspicion.” The general idea is that we give very short shrift to what our opponents actually think–to the objective case they are making–and instead rush quickly past it to psychological analysis that takes their error for granted and indulges in self-satisfied dissection of their inferiority. I’m not saying we can indulge in zero time spent on analyzing the motives or intentions of our interlocutors, but I do think we should try to shift the balance onto the arguments at hand and take them seriously. And, on that basis, Shirky’s argument that protest votes are indistinguishable from non-voting, simply do not hold up to any level of scrutiny.

Now, at the very end, I want to return to the first comment I made about personal taste and conscience. Here is the beginning of Shirky’s concluding paragraph:

None of this creates an obligation to vote, or to vote for one of the two viable candidates. It is, famously, a free country, and you can vote for anyone you like, or for no one.

If Shirky really believes that there is no obligation to vote for a major party candidate, than his entire essay collapses into nonsense. The whole point–from start to finish–is that protest voters are selfish egotists who are abdicating their duty and “making the rest of us do the work of deciding.” If that isn’t a violation of an obligation, then what on Earth could be?

That fact that we are allowed under the law to behave in a certain way is not the only nor the final word on what our obligations may or may not be. The set of things that are obligatory (in any sense) and the set of things that are legally required are not the same. So–far from celebrating a genuine sense of freedom in which government refrains from attempting to demarcate the boundaries of the permissible–Shirky is engaging in a kind of totalitarian thinking in which what we must do and what the law requires are assumed–despite all common sense–to be identical.

This is not an incidental misstep. It’s integral to Shirky’s case. After all, if a protest vote is really just a matter of personal preference–if I prefer Candidate Alice to Candidate Bob in the same way in which I prefer rocky road to mint chocolate chip or blue to red–then it would be the height or selfishness to become an absolute stickler on that point to the detriment of the group. This is a world of moral relativism, where all moral decisions are reflections of personal preference and can pretend to no greater validity.

It’s not a very coherent world. In it, Shirky first argues that protest votes are immoral because they place one’s personal preferences ahead of the common good. But, in this incoherent world, Shirky has to immediately repudiate his own argument. You are an arrogant, hypocritical egoist if you vote third party! Not that that means you can’t do it, of course. You can do whatever you’d like. Who am I to judge? I’m not saying. I’m just saying. The whole thing collapses into irrelevant, incomprehensible muttering.

But if there is such a thing as an objective moral reality, then when a person refuses to vote the way you’d like them to out of conscience, you can’t simply browbeat them for being selfish. Perhaps they are! But perhaps they are acting out of an earnestly held believe in a universally applicable moral stand, one that does not suddenly become irrelevant or disposable merely because it is unpopular or inconvenient. And so, in this world, the specifics actually matter. In this world, some people who vote third party are irresponsible and selfish and some are responsible and selfless. It’s frustrating that we can’t always line up the good guys and the bad guys based on how they vote. It’s downright dangerous when we try to do so anyway.

Shirky offers a thin pretense of not telling you how to vote, but in fact he not only tells you how to vote, but specifically who to vote for.[ref]Does anyone think for an instant he is voting for Donald Trump?[/ref] His post has a form of non-judgmentalism but denies the power thereof. I’ll do you the courtesy of not pretending to be neutral. Instead, I’ll just go ahead and tell you what I think you should do without any caveats or qualifications: you should vote, and you should vote informed, and you should vote your conscience. Consider the costs and the benefits of voting for one of the two candidates who will almost certainly win vs. the costs and benefits of voting for a candidate who will almost certainly not win. Take it it seriously, do your homework, and if you’re religious pray for guidance. Then vote accordingly.

And hey, if you’re looking for a silver lining during this awful election, here’s one. In the past, I always felt that there was a clear-cut candidate that should win. There was always a little strain and tension when family or close friends felt the same, but about the other guy. This year, I don’t have that strain. It’s all a mess, and I can see compelling cases for voting in a lot of different ways. I have people I respect voting for Clinton, voting for Trump, voting for Johnson, and voting for McMullin.[ref]No one I know is voting for Stein, that I’m aware of.[/ref] And–for the first time–I actually have absolutely zero reservations about their voting differently than I am. Not to say I agree with all of them–I don’t! I can’t!–but I can see where they are coming from. So that, at least, is a nice side-effect of this ongoing train wreck.

This whole essay would be moot if we would improve our voting system and move to something like Approval Voting. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Approval_voting

Then you can vote for any number of candidates you think reasonable.

Yes, first-past-the-polls voting is very antiquated and we’re probably due for an upgrade to bring us out of the 18th century of voting technology.

Nathaniel,

I have a feeling that you and I closely align on political matters in general and this election in particular. I keep having this inner debate about not voting vs. voting third party vs. voting for one of the two despicable major party candidates if only to stave off the worse of the two (which is actually worse is another inner debate going on). If the libertarians hadn’t nominated such a non-libertarian, it’d be a no-brainer for me. As is, Gary Johnson is almost as bad as the other three candidates (incl. Jill Stein), and certainly not someone I would vote for with the least bit of enthusiasm. This is easily the most frustrating and depressing election cycle of my adult life. Right now I’m leaning toward thinking that Trump is bad enough that if he wins, so tainted will be the Republican (ostensibly conservative) brand by his bad decisions and generally incoherent philosophy and bizarre behavior that another Republican will not win the White House for another 20 years (if ever again since by that time the drift to socialism will have gotten that much worse).

At this point I’m looking for any political balm that will soothe my political wounds. I appreciate the blog and am grateful you (and your associates) are providing at least a little relief to me.

Also enjoying the Odyssey!

Thanks to Tyler for introducing the concept of Approval Voting which I had not heard of before!

I’m glad you’ve come around on this. I remember you didn’t think this way last election. But then, we are staring in the face of Armageddon.

One point I didn’t understand from Shirky’s original post, and that I didn’t see addressed here, is the idea of voting third party as being selfish. How? It assumes that by not voting for Democrat or Republican, I’m hurting others, but hurting them how? The worst that could happen from voting third party is that the candidate I vote for doesn’t get elected and the D or R does instead… but that’s also what would happen if we all voted for D or R like he wants us to.

So where is the harm coming from?

I personally think I’m voting altruistically, by voting for a candidate whose platform I think will do the most good for the country and the world.

Wouldn’t voting for a candidate I earnestly believe will ruin both, be kind of a morally terrible thing to do? Isn’t that the vote that actually hurts others? The one he’s telling us to make?