The heated debate over school choice was sparked again by the nomination and appointment of Betsy DeVos to Secretary of Education. I’m not so much interested in DeVos as I am the evidence regarding school choice. One professor claims that economists are skeptical of school choice, with only 1/3 of economists supporting it. John Oliver has even taken charter schools to task.[ref]If you need a rundown on what a charter school actually is, this NPR article is helpful.[/ref] As Reason summarizes,

Oliver’s segment…was almost unrelieved in its criticism of charters. Echoing the talking points of major teachers unions and liberal interest group such as People for the American Way and the NAACP, the HBO host attacked charters for being unaccountable to local and state authorities (this is not true, as all state charter laws have various types of oversight rules built into them), “draining” resources from traditional public schools (which presumes tax dollars for education belong to existing power structures), and skimming students (in fact, charters teach a higher percentage of racial and ethnic minorities than traditional public schools; they also serve a higher percentage of economically disadvanataged kids). Which is not to say that Oliver is all wrong in his analysis. For instance, he ran through a series of charters that were criminally mismanaged and deserved to be shut down (even as he glossed over the fact that failing charters, unlike failing traditional schools, are more likely to be closed). And he’s right to argue that, on average, charters perform about the same as regular public schools. However, such comparisons tell us very little about whether charters do help those at-risk students better than traditional schools. On this score, there is very little doubt that charters do more with less money and fewer resources.

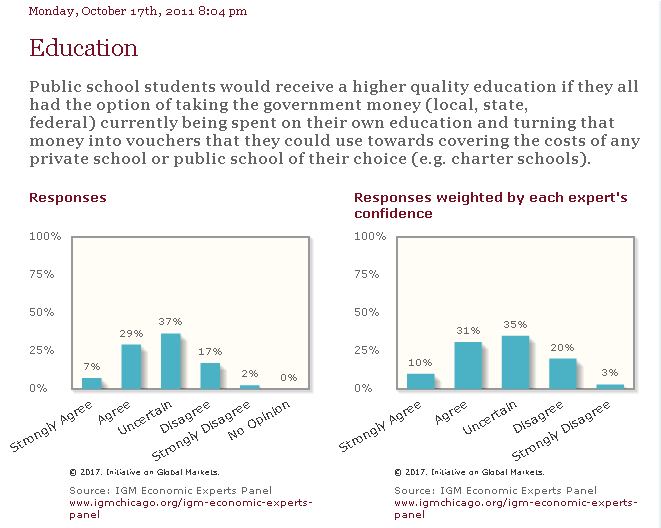

So what is the evidence? First and foremost, the claim “only a third of economists on the Chicago panel agreed that students would be better off if they all had access to vouchers to use at any private (or public) school of their choice” is misleading if not technically incorrect. Here’s the poll:

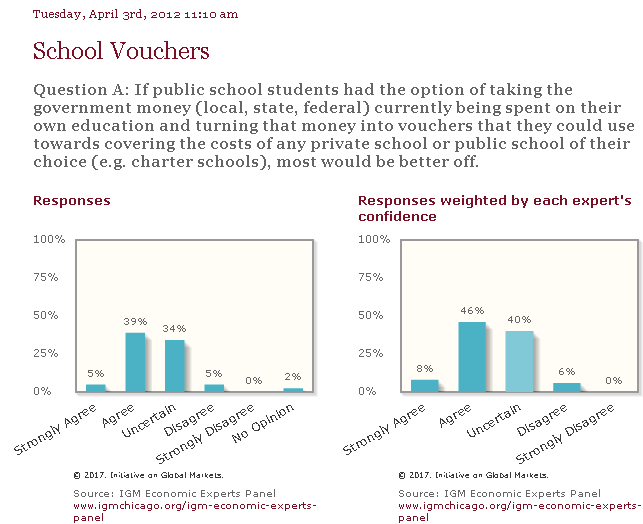

As Slate Star Codex responds, “A more accurate way to summarize this graph is “About twice as many economists believe a voucher system would improve education as believe that it wouldn’t.” By leaving it at “only a third of economists support vouchers”, the article implies that there is an economic consensus against the policy. Heck, it more than implies it – its title is “Free Market For Education: Economists Generally Don’t Buy It”. But its own source suggests that, of economists who have an opinion, a large majority are pro-voucher.” This is especially true when you look at a more recent poll:

But what about empirical evidence? Harvard’s Martin West sums up the evidence for school choice as such:

First, the benefits of attending a private school are greatest for outcomes other than test scores—in particular, the likelihood that a student will graduate from high school and enroll in college. Second, attending a school of choice, whether private or charter, is especially beneficial for minority students living in urban areas. These findings support the case for continued expansion of school choice, especially in our major cities. They also raise important questions about the government’s reliance on standardized test results as a guide for regulating the options available to families.

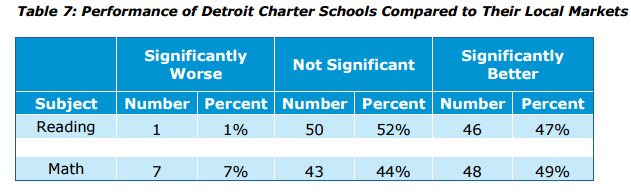

For example, a 2013 study found that private-school vouchers have no significant effects on college enrollment except for African-American and Hispanic students. The impact on the former was substantial, while the latter was small and statistically insignificant. Another study that has been trumpeted as demonstrating that “Detroit’s charter schools performed at about the same dismal level as its traditional public schools” actually supports quite the opposite.

The study concludes,

Based on the findings presented here, the typical student in Michigan charter schools gains more learning in a year than his TPS counterparts, amounting to about two months of additional gains in reading and math. These positive patterns are even more pronounced in Detroit, where historically student academic performance has been poor. These outcomes are consistent with the result that charter schools have significantly better results than TPS for minority students who are in poverty (pg. 44).

Margaret Raymond, Director of Stanford’s Center for Research on Education Outcomes (CREDO),[ref]The group behind the study mentioned above.[/ref] authored a Huffington Post piece to correct some misperceptions about what the evidence shows regarding charter schools. Referring to a 2013 study, Raymond writes,

The main findings of the report are as follows. Over the course of a school year, charter school students learn more in reading than district public schools — it is as if the charter school students attended about seven more days of school in a typical school year. The learning in math is not statistically different (not worse as she claims).

[But these] results…are the average one-year growth, blending brand new charter school enrollees with students with longer persistence. When the length of time a student attends a charter school is taken into account, the results are striking: In both reading and math, we discovered that students’ annual progress rose strongly the longer they attended charter schools. For students with four or more years in charter schools, their gains equated to an additional 43 days of learning in reading and 50 additional days of learning in math in each year.

Second, the results showed strong improvement for the sector overall — the proportion of charter schools outperforming their local district schools rose and the share that underperformed shrank in both reading and math compared to performance four years earlier. The shift in performance is neither idle drift nor nefarious conduct on the part of charter schools — we found no differences in the demography of students served by charter schools over the period.

…Urban low income and minority students are the ones best advantaged in charter schools. CREDO released “The Urban Charter School Study“ in 2015, a report conveniently overlooked by Weingarten. We found that gains in urban charter schools are dramatic overall (equivalent to 28 days of additional learning in reading and 40 days of additional learning in math every year) but for low income minority students they are nothing short of liberating: as much as 44 extra days of learning in reading and 59 extra days in math.

Jay P. Greene, Distinguished Professor and Head of the Department of Education Reform at the University of Arkansas, notes,

According to the Global Report Card, more than a third of the 30 school districts with the highest math achievement in the United States are actually charter schools. This is particularly impressive considering that charters constitute about 5% of all schools and about 3% of all public school students. And it is even more amazing considering that some of the highest performing charter schools, like Roxbury Prep in Boston or KIPP Infinity in New York City, serve very disadvantaged students.

He continues,

[W]e have four RCTs on the effects of charter schools that allow us to know something about the effects of charter schools with high confidence. Here is what we know: students in urban areas do significantly better in school if they attend a charter schools than if they attend a traditional public school. These academic benefits of urban charter schools are quite large. In Boston, a team of researchers from MIT, Harvard, Duke, and the University of Michigan, conducted a RCT and found: “The charter school effects reported here are therefore large enough to reduce the black-white reading gap in middle school by two-thirds.”

A RCT of charter schools in New York City by a Stanford researcher found an even larger effect: “On average, a student who attended a charter school for all of grades kindergarten through eight would close about 86 percent of the ‘Scarsdale-Harlem achievement gap’ in math and 66 percent of the achievement gap in English.”

The same Stanford researcher conducted an RCT of charter schools in Chicago and found: “students in charter schools outperformed a comparable group of lotteried-out students who remained in regular Chicago public schools by 5 to 6 percentile points in math and about 5 percentile points in reading…. To put the gains in perspective, it may help to know that 5 to 6 percentile points is just under half of the gap between the average disadvantaged, minority student in Chicago public schools and the average middle-income, nonminority student in a suburban district.”

And the last RCT was a national study conducted by researchers at Mathematica for the US Department of Education. It found significant gains for disadvantaged students in charter schools but the opposite for wealthy suburban students in charter schools. They could not determine why the benefits of charters were found only in urban, disadvantaged settings, but their findings are consistent with the three other RCTs that found significant achievement gains for charter students in Boston, Chicago, and New York City.

When you have four RCTs – studies meeting the gold standard of research design – and all four of them agree that charters are of enormous benefit to urban students, you would think everyone would agree that charters should be expanded and supported, at least in urban areas. If we found the equivalent of halving the black-white test score gap from RCTs from a new cancer drug, everyone would be jumping for joy – even if the benefits were found only for certain types of cancer.

There is even some evidence that school choice can decrease crime. Harvard’s David Deming explains,

I find that winning a lottery for admission to a preferred school at the high school level reduces the total number of felony arrests and the social cost of crime. Among middle school students, winning a school-choice lottery reduces the social cost of crime and the number of days incarcerated. Importantly, I find that these overall reductions in criminal activity are concentrated among students in the highest-risk group. Indeed, I find little impact either positive or negative of winning a school-choice lottery on criminal activity for the 80 percent of students outside of this group.

Consider first the results for high school students in the high-risk group. Among these students, winning admission to a preferred school reduces the average number of felony arrests over the study period from 0.77 to 0.43, a pattern driven largely by a reduction of 0.23 in the average number of arrests for drug felonies (see Figure 2). The average social cost of the crimes committed by high-risk lottery winners (after adjusting the cost of murders downward) is $3,916 lower than for lottery losers, a decrease of more than 35 percent. (Without adjusting for the cost of murder, I estimate the reduction in the social cost of crimes committed by lottery winners at $14,106.) High-risk lottery winners on average commit crimes with a total expected sentence of 35 months, compared to 59 months among lottery losers.

Among high-risk middle-school students, I find no effect of winning a school-choice lottery on the average number of felony arrests. Although the number arrests for violent felonies falls, this is offset by an increase in the number of property arrests. Because violent crimes carry greater social costs, however, winning a school-choice lottery reduces the average social cost of the crimes committed by middle school students by $7,843, or 63 percent. It also reduces the total expected sentence of crimes committed by each student by 31 months (64 percent).

With expenditure per pupil increasing dramatically over the last century (the U.S. spends more per student than almost every other country), it’s disheartening to find out how much the productivity of education has declined. Brooking’s Jonathan Rothwell explains,

For the nation’s 17-year-olds, there have been no gains in literacy since the National Assessment of Educational Progress began in 1971. Performance is somewhat better on math, but there has still been no progress since 1990. The long-term stagnation cannot be attributed to racial or ethnic differences in the U.S. population. Literacy scores for white students peaked in 1975; in math, scores peaked in the early 1990s.

International literacy and numeracy data from the OECD’s assessment of adult skills confirms this troubling picture. The numeracy and literacy skills of those born since 1980 are no more developed than for those born between 1968 and 1977. For the average OECD country, by contrast, people born between 1978 and 1987 score significantly better than all previous generations.

Comparing the oldest—those born from 1947 to 1957—to youngest cohorts—those born from 1988 to 1996, the U.S. gains are especially weak. The United States ranks dead last among 26 countries tested on math gains, and second to last on literacy gains across these generations. The countries which have made the largest math gains include South Korea, Slovenia, France, Poland, Finland, and the Netherlands.[ref]This is the difference between cognitive skills and merely going to school.[/ref]

Rothwell in part points to “a decline in bureaucratic efficiency” in primary and secondary education.[ref]He also acknowledges “that teaching itself has become increasingly unattractive.” We could maybe learn from Finland in this regard.[/ref] With declining productivity in schools, it’s worth pointing out that some economic evidence finds that competition in public-school districts boosts school productivity, raises student achievement, and decreases spending. Furthermore, recent evidence shows that “autonomous government schools” (e.g., charters) have higher management quality than regular public or private schools. This higher management quality in turn is strongly linked to better pupil outcomes.

A 2016 meta-analysis of global voucher RCTs concluded,

For reading impacts, overall, we find positive effects of about 0.17 standard deviations (null for US programs, 0.24 standard deviations for non-US programs)…For math scores, we report 10 meta-analytic ITT effect sizes (seven in the US and three outside of the US). Overall, vouchers have a positive effect on math of 0.11 standard deviations, 0.07 standard deviations in the US and 0.15 standard deviations outside of the US.

The overall results just described in this section are for the final year of data in each study. It could be that these effects are not representative of the initial effects one might expect from a new program. In fact, our analysis of the effects by year indicates that the effects of private school voucher programs often start out null in the first one or two years and then turn positive. Longer-term achievement effects, of course, are much more salient than immediate achievement effects whenever longer-term effects are available

…Additionally, in terms of policy implications, it is critical to consider the cost-benefit tradeoffs associated with voucher programs. Wolf & McShane (2013) and Muralidharan et al. (2015) found that vouchers are cost effective, since they tend to generate achievement outcomes that are as good as or better than traditional public schools but at a fraction of the cost. The greater efficiency of school choice in general and school vouchers in particular are another fruitful avenue for scholarly inquiry (pgs. 39-41).

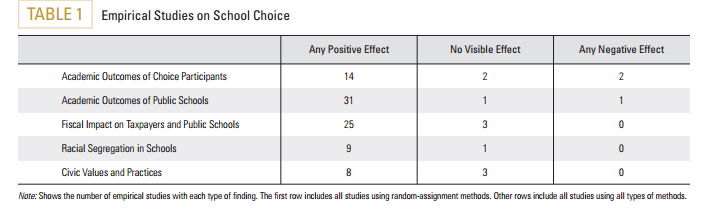

Another 2016 study looked at the various empirical studies that have been conducted on school choice. The following chart lists the key findings:[ref]Some of the negative findings were arguably due to overregulation.[/ref]

Given these positive findings, it’s little wonder that a majority of Americans are dissatisfied with our education system while a large majority support school choice (especially parents). Granted, there are empirically-tested ways to improve regular public schools and I’m all for it. But with the evidence above, maybe school choice isn’t the bogeyman it has been made out to be.[ref]A bogeyman largely created by teachers’ unions, which tend to harm children’s prospects.[/ref]

Thanks, Walker. Personally, I like the idea of charter schools. I don’t like the idea of private school vouchers. I’m not against choice; I’m just against federal funding of sectarian education and social fragmentation. Unfortunately, Betsy DeVos’s core agenda is the latter, not the former.

Yeah, that’s why I wanted to focus on the argument over school choice instead of DeVos. Unfortunately, I think people are conflating the two. And not all school choice is created equal. For example, the study I cite about management quality finds that charter school management is significantly better than private schools.