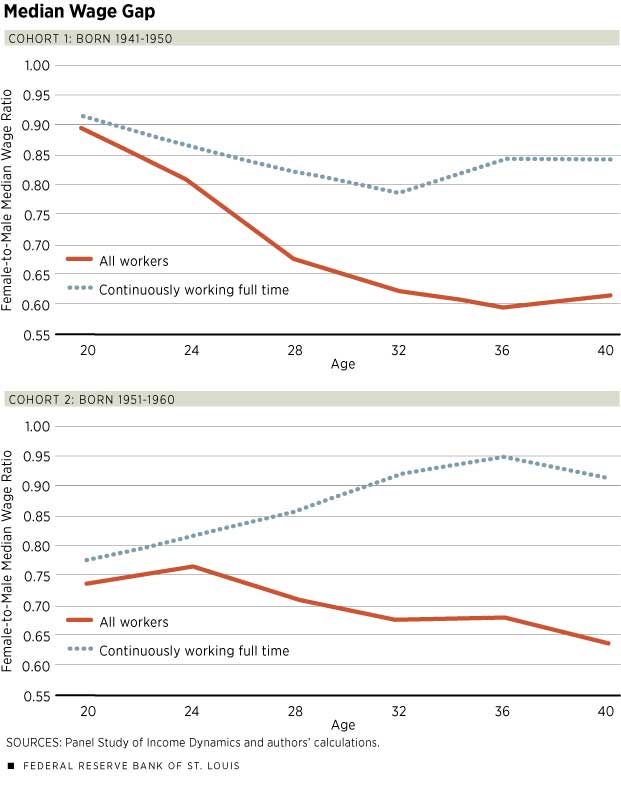

I’ve written about the gender wage gap before. An October 2016 article in the St. Louis Fed’s The Regional Economist “examine[s] the evolution of the wage gap by cohorts” as well as “the evolution over the life cycle to gain further insight into the patterns and possible causes of the gender wage gap.” The researchers find that

the gap increases with age, at least after the age of 24, which is the age by which the majority of individuals have completed their education. Thus, the gender gap when workers are 24 is substantially smaller than the gap when workers are in their mid-30s. This fact is well-known, and one of the main reasons for this pattern is that men and women make different choices over the life cycle. As they get older, women are more likely than men to work fewer hours outside the home and have breaks in their labor force participation (yielding less accumulated experience and possibly fewer labor market skills) and are less likely to hold highly compensated jobs with promotion prospects.

But why a gap at all?

Specifically, firms often have costs of hiring and training workers. When they hire people for jobs with good promotion prospects and jobs that require training and long hours, they are likely to seek individuals who are less likely to leave the labor force or to reduce their hours substantially. While some women are more inclined to participate in the labor market and work full time, women in general are still more likely to reduce hours or leave the labor force, especially during childbearing years, relative to what men are likely to do. This can lead to lower wages for equally qualified women. Furthermore, since many factors affecting labor supply are not known to employers at the time of hiring, even women who are likely to work long hours and are attached to the labor market as much as men are may earn lower wages because, on average, women with the same qualifications as men are less attached to the labor force than men are.

This type of discrimination is often called statistical discrimination because group affiliation and group averages adversely affect individuals in the group. Over time, employers can typically observe work experience, whether individuals were working and whether they were working full time or part time. Therefore, employers can increasingly identify workers who are less attached to the labor market and, as a result, discrimination of the type described above goes down with age. Since this type of discrimination is more likely to be directed at women, the wages of women who work full time continuously may grow relative to the wages of men due to a decline in discrimination.

They note,

We investigated the changes in the education composition of men and women who work full time continuously in each cohort. For the group working full time continuously in the first cohort [1941-1950], females were more educated than males up to age 28; however, the wage gap is declining when males are more educated than females. In the second cohort [1951-1960], the education gap among those working full time continuously declines (with females being more educated than males in all age groups). Thus, education composition does not explain the evolution of the gender pay gap differences in that group.

They conclude,

By comparing the differences in the evolution of the gender pay gap not only by age but by full-time/part-time status, we demonstrated the importance of statistical discrimination and its relationship to labor force participation of women. As one would expect, this type of discrimination plays a smaller role for the third cohort (born 1961-1970) because women in this cohort are more attached to the labor force than women in the past.