Toward the end of last year, I did a rundown of the data on racial bias and policing. A new study is worth adding to the list. According to its findings,

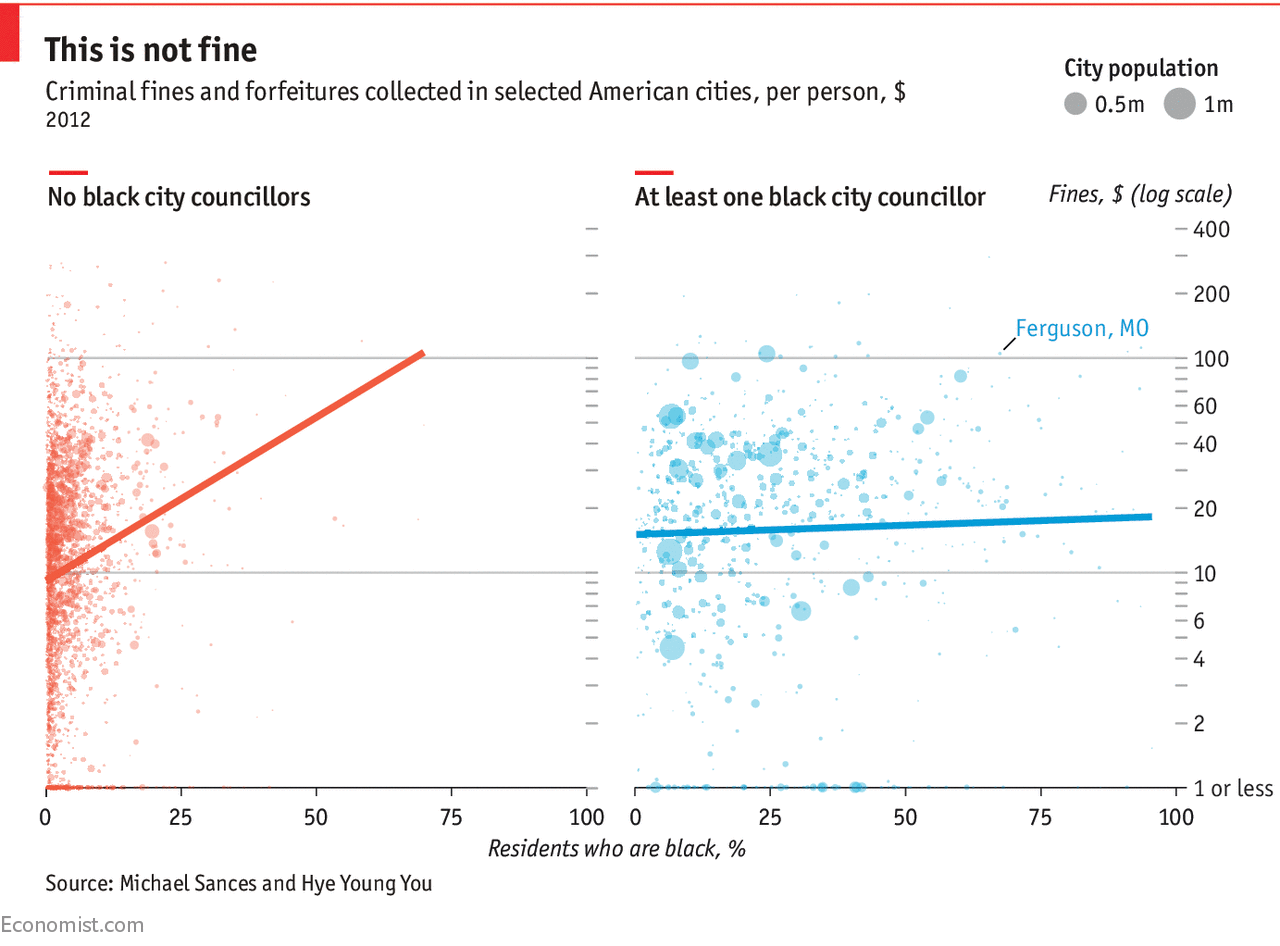

Ferguson was unlikely to be a unique outlier, and other cities engaging in similar practices might well have continued outside of the national spotlight. A new paper by Michael Sances of the University of Memphis and Hye Young You of Vanderbilt University published this month in the Journal of Politics found that Ferguson was indeed more of a rule than an exception. After examining data on 9,000 American cities, they found that those with more black residents consistently collected unusually high amounts of fines and fees—even after controlling for differences in income, education and crime levels. Cities with the largest shares (98%) of black residents collected an average of $12-$19 more per person than those with the smallest (0%) did.

However, there was one subgroup of cities that bucked the trend: the relationship between race and fines was only half as strong in places whose city councils included at least one black member. This may be because black politicians are likelier than white ones are to respond to complaints from black constituents. Black councillors might also intervene to stop certain policies, like increasing court fees, from going into effect to begin with.

What fines are we talking about exactly?

For example, in Peoria, Arizona, two people were jailed for not trimming weeds more than six inches tall. In Ferguson, a black man resting in his car after playing basketball in the public park was stopped by police and charged with, among other things, not wearing a seat belt in his (parked) car and making a false declaration after giving the officer a shortened name (like “Bob” instead of “Robert”). Such fines may fall disproportionately on the backs of black citizens, because they tend to be poorer and lack the resources to contest the penalties.

Despite the exhaustive controls the authors included in their study, the strong correlation they found does not demonstrate decisively that race is the ultimate cause of higher fines. However, it does put a very high burden of proof on researchers arguing that some other factor is responsible. Now that the pattern has been identified across the country, city governments that rely heavily on fines would be well-advised to consider more transparent sources of revenue, and ones that do not place an additional burden on a subset of residents who are already disadvantaged.

Check it out.