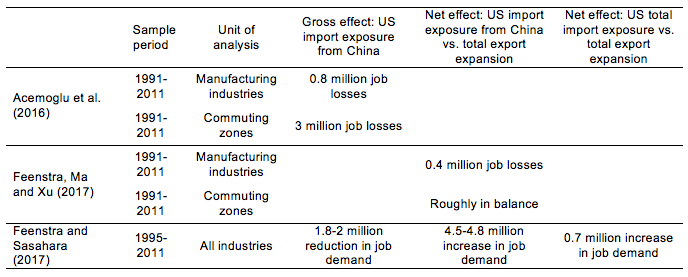

I’ve talked about the China Shock before. The concern is that imports from China reduced the amount of jobs in the United States. However, new research suggests otherwise:

Our empirical results show important job gains due to US export expansion. We find that although imports from China reduce jobs, the global export expansion of US products creates a considerable number of jobs. Based on the industry-level estimation, our results show that on balance over the entire 1991-2007 or 1991-2011 periods, job gains due to changes in US global exports largely offset job losses due to China’s imports, resulting in about 300,000 to 400,000 job losses in net. Estimation at the commuting zone level generate even bigger job creation effects: in net, global export expansion substantially offsets the job losses due to imports from China, resulting in about 200,000 net job losses over the period 1991-2007, and a roughly balanced net effect if we extend the analysis to 1991-2011.

In Feenstra and Sasahara (2017), we quantify the employment effect of US imports and exports using a global input-output analysis. Following the technique of Los et al. (2015), we use the world input-output table from WIOD and examine the employment effects of US total exports and imports from China and from all countries during the period 1995-2011. Admittedly, this approach only indicates the impact of trade on labour demand, without taking into account the (regional) supply of labour in general equilibrium.

We find that the growth in US exports created demand for 2 million manufacturing jobs, 500,000 resource-sector jobs, and a remarkable 4.1 million jobs in services, totalling 6.6 million. The positive job creation effect of exports in the manufacturing sector, 2 million, is quantitatively similar to the result in Feenstra et al. (2017), in which 1.9 million jobs were created by US exports from the instrumental-variable regression approach. On the import side, our analysis shows that manufacturing imports from China reduced demand for US jobs by 1.8-2.0 million, which is similar to the result in Autor et al. (2016), who finds a decline of 2.0 million jobs due to imports from China.

One advantage of the input-output approach is that it is easy to extend the analysis to other sectors such as services and natural resources. Our results show that, when focusing on the manufacturing sector and the natural resource sector, the net effect of overall trade with all countries in all sectors is slightly negative: 80,000 reduction in demand for jobs in manufacturing, and a 250,000 job reduction in the natural resource sector during 1995-2011. However, when looking at the service sector, we find a substantial net job gain, with a 1.03 million increase in the demand for jobs due to overall trade with all countries. This is large enough to compensate for the net job losses in the manufacturing and natural resource sectors. After taking all of these into account, the net effect of overall trade with all countries led to a net increase in labour demand of 700,000 jobs.

They conclude,

Our results fit the textbook story that job opportunities in exports make up for jobs lost in import-competing industries, or nearly so. Once we consider the export side, the negative employment effect of trade is much smaller than is implied in the previous literature. Although our analysis finds net job losses in the manufacturing sector for the US, there are remarkable job gains in services, suggesting that international trade has an impact on the labour market according to comparative advantage. The US has comparative advantages in services, so that overall trade led to higher employment through the increased demand for service jobs.