Four days ago The Independent (an online UK magazine) ran this story: Bulletproof backpacks for children reflect a new reality in America. The article, and plenty like it, are leading to dramatic Facebook posts from or about teachers about how they help their high school students deal with the new reality that they might be gunned down in their schools at any time. Parents are afraid, kids are afraid, teachers are afraid, everyone seems to be afraid.

But why?

And no, I’m being earnest here. Why?

If there’s one topic that’s been prominent in media over the past few years, it’s been human irrationality. For a while there, “cognitive bias” threatened to become almost as much of a buzzword as “machine learning” has become, and it seemed like Wikipedia’s list of cognitive biases was getting a new entry every day. Everyone in any academic discipline even tangentially related to how humans evaluate risk–evolutionary psychology, economics, finance, etc. etc.–had a new book or a new study that showed how bad humans are at evaluating risk.

Some of the most prominent cognitive biases studied in experiments and written about in the popular press include the availability heuristic and the recency effect. So we know–or at least we should know–that in the immediate wake of a horrific school shooting our cognitive biases are going to go into overdrive to exaggerate the threat. This isn’t unique to school shootings. We do the same thing with all kinds of dramatic/traumatic events, especially terrorism. More Americans died because of the shift from flying to driving in the wake of 9/11 than died in the attack themselves. The fear of terrorism was quite literally more deadly than actual terrorism.

This over-reaction to the threat of terrorism has had horrific consequences. Some have been felt here in the United States, including the erosion of civil liberties and a lamentably paranoid tinge to any discussion of immigration, but for the most part we (ordinary Americans) have been free to go about our lives because we have outsourced the cost of our fear-driven policies. We don’t pay the price. The small minority of Americans who volunteer to serve in the armed forces pay the price–including physical and mental trauma that no amount of yellow ribbons at home can compensate for–along with children killed in drone strikes, collateral damage from American interventionism, and desperate refugees who were barred a safe escape.

Now, in the wake of another awful school shooting, we’re witnessing again America’s masochistic addiction to panic and fear.

If you read an article like the one from The Independent or this one from The Cut or any of the thousands[ref]I’m guessing, based on the fact that I’ve seen several in my own feed[/ref] of emotional Facebook posts about how teachers and students shouldn’t have to fear for their lives just because they’re going to school, then you’d think we were suffering some kind of massive tidal wave of school shootings.

But what’s actually going on?

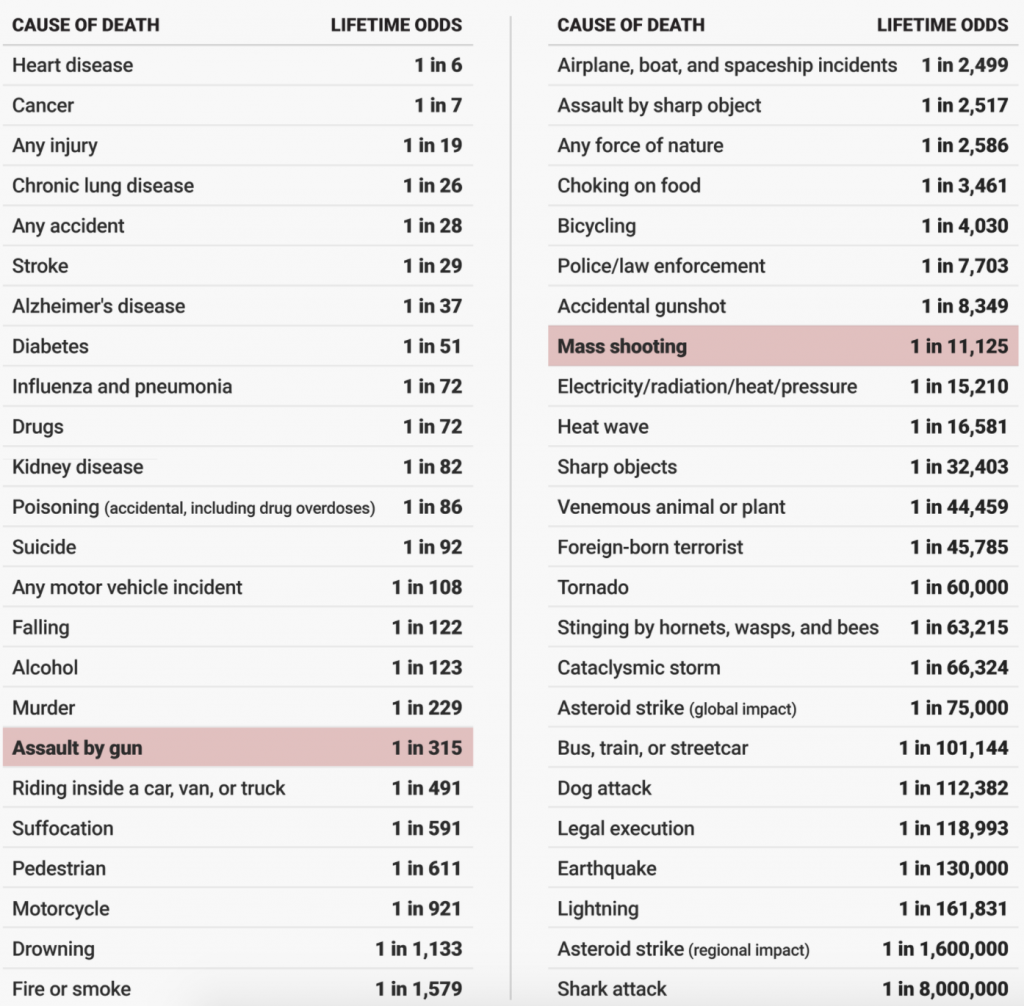

Enter Business Insider with their article: How likely is gun violence to kill the average American? The odds may surprise you. The centerpiece of the article is this chart, which compares lifetime odds (for Americans) of dying from various causes:

Right off the bat, the odds of dying in a school shootings are significantly lower than the kinds of deaths that we Americans don’t fear: car accidents, drowning, choking are all much more likely to end your life than a mass shooting. What’s even more interesting, to me, is that you are apparently more likely to die because a police officer killed you than because a mass shooter killed you.

However, a major problem with the Business Insider numbers is that they aren’t talking about school shootings, they’re talking about “mass shootings” with the definition of “any event where four or more victims were injured (regardless of death)”.

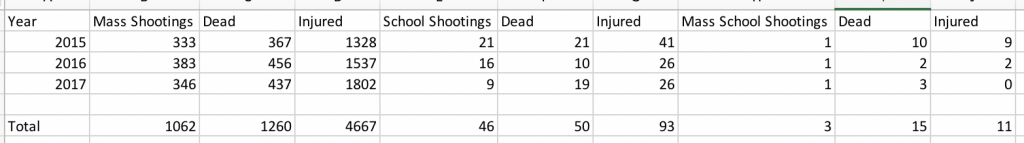

I went to Wikipedia and created two lists of my own. One of all the school shootings for 2015 – 2017 (the same years as the data available from the BI article) and another of all the school shootings that fit the popular perception of a school shooting. I called this narrowest category “mass school shootings” and I counted any shooting perpetrated by a student / former student resulting in at least 2 fatalities (other than the attacker) at a school. This table illustrates what the numbers look like using these three different categories:

From this, I’m able to calculate the lifetime odds of death from the two new categories: school shootings and mass school shootings. Compared to the 1 in 11,125 odds for any mass shooting, the odds of dying in a school shooting are 1 in 280,350 and the odds of dying in a mass school shooting are 1 in 934,500.

First, let me deal with a couple of quick math issues. These numbers are for all people. Obviously a random 70-year old is unlikely to be in a school and so is much, much less likely to die in a school shooting, and a high school student is (relative to some random 70-year old) much, much more likely. But if you want to do a relative comparison, then you should keep this list as-is. The only way to get the risk assessment for high school students (or all K-12 students, or all K – college students) would also be to look at their likelihoods of dying across all the categories. You’d see heart disease drop off the list, but you’d also see car accidents go much higher. So no: this is not scientific. These are what I’d call back-of-the-envelope calculations. And according to them, you’re more likely to die from being struck by lightning than from a school shooting (category #2) and the only things on the BI table less likely to kill you than a mass school shooting (category #3) is a regional asteroid impact or a shark attack.

Asteroids and shark attacks, people.

I know people are going to be mad at me for being insensitive, but maximum sensitivity isn’t always the right course. When you have a child–your own child or a kid that you’re responsible for–and they are afraid of something than your job as an adult is more than empathy. You can’t just share the child’s fear. You have to allay that fear when possible.

When my children were younger, they were really, genuinely afraid of dying in a tornado. We had moved from Virginia to Michigan and they heard the tornado sirens being tested every now and then, and so they were afraid. Part of my job was to empathize. Part of my job was also to allay their fears by explaining realistically that–while dangerous–tornados were not that common.

More recently, one of my children came to me and confided with a quaver of real fear in their voice that they thought they might have tetanus because “my jaw is starting to feel kind of tight.” This is funny to us, but my kid was really, truly scared and on the verge of tears. My job was not to participate in their fear. It also wasn’t to mock their fear. It was to empathize but–again–allay the fear.

Please note that this doesn’t mean I’m trivializing the devastation of an actual tornado. During the tornado outbreak of Dec 2015, 13 people were killed. Nothing about that is funny. Nothing about that is trivial. Tetanus isn’t a joke, either. Because of vaccinations, only a few people die in the US every year from tetanus, but historically it was a real killer and it continues to be a serious health concern in many parts of the world (especially India).

So I’m not trivializing terrorism when I point out that more people died from avoiding planes after 9/11 than died on 9/11. I’m not trivializing tetanus or tornados when I help allay my kids’ fears. And I’m not trivializing school shootings when I point out that our fears of them are vastly overblown.

Far from it. The reason I’m writing this is that it broke my heart to read a post from a friend on Facebook about how his wife (a teacher) could do nothing but share the fear and panic of her high school students. They are afraid, and she wasn’t able to offer anything substantive to combat that fear. I don’t blame her personally for that at all, but–as a society–we should be mature and sober enough to tackle risk and fear responsibly. We need to do better for our kids.

I think I know the answer to my question. I know why we’re addicted to fear. Some of it is human nature, as we mentioned already. Evolutionarily, risks are more important than rewards. But there’s more to it than that.

For one thing, fear is profitable. It drives traffic and donations. That explains most of what human nature alone cannot.

But I have my suspicions that it doesn’t explain everything. I wonder if human beings are calibrated to a certain degree of threat and risk in our lives. And–living in what is without any doubt the safest and most comfortable period of human history–it’s almost as though we are incapable of accepting that realty and intent on manufacturing risks and dangers we keep expecting to be there, but aren’t.

This post is not about gun control or even school shootings in particular.

It’s just about risk, and fear, and how we need to deal better with the fear if we want–individually and as a society–to find ways to batter manage risk.