In short, ignorance and fear of the unknown or “the other” (which ends up manifesting as racial resentment) lead to anti-immigration sentiments. Many have been quick to point out that economic anxieties didnot play a significant role in the rise of Trump. Cultural values, for example, played a far more significant role. Evidence from Belgium also suggests that declinism–a negative view of the state and evolution of society–is far more important in predicting populist support than economic insecurities. Nonetheless, there is some evidence that economic downturns and uncertainty do lead to a rise in populism, particularly in Europe. Increases in unemployment following the Great Recession eroded trust in mainstream political parties in Europe and led to a rise in support for populist parties. Harvard’s Dani Rodrik has made a case that economic globalization helped create a populist political backlash.

Nostalgia may be a better predictor of populist sentiments.[ref]Psychological research supports this.[/ref] Roughly six-in-ten French adults with a positive view of the populist National Front (62%) say life in France is worse today for people like them than it was 50 years ago. Only about four-in-ten (41%) of the rest of the French population share that perspective. In Germany, 44% of [Alternative for Germany] supporters say life today is worse than 50 years ago; that compares with just 16% of other Germans. Those with populist sympathies in Sweden and the Netherlands similarly lament the passing of better times in the past.

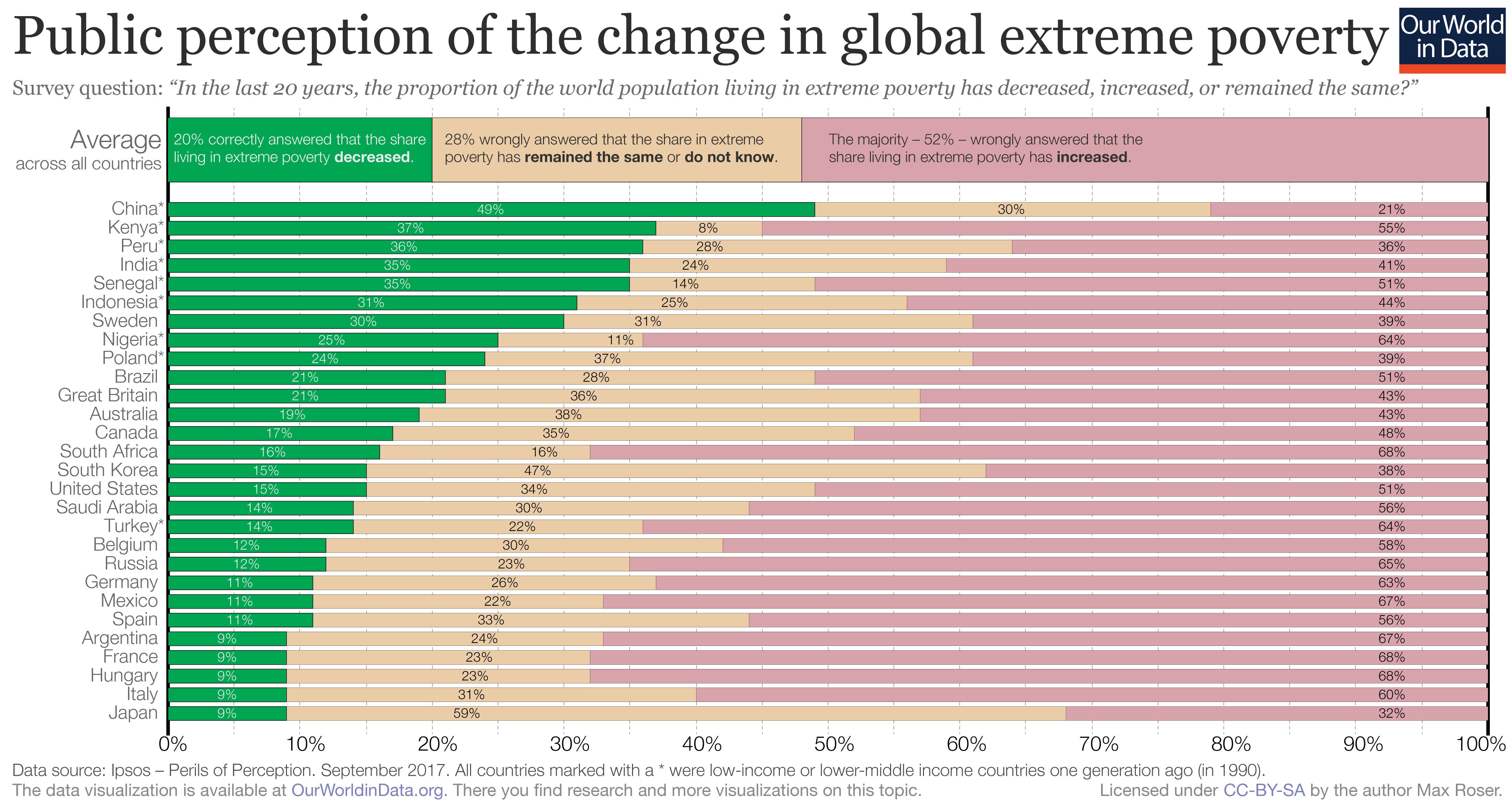

The link between populism and declinism is disconcerting, especially given poll numbers from a 2017 study conducted by Ipsos with the Gates Foundation. Economist Max Roser at Our World in Data has provided the answers in graph formation below:

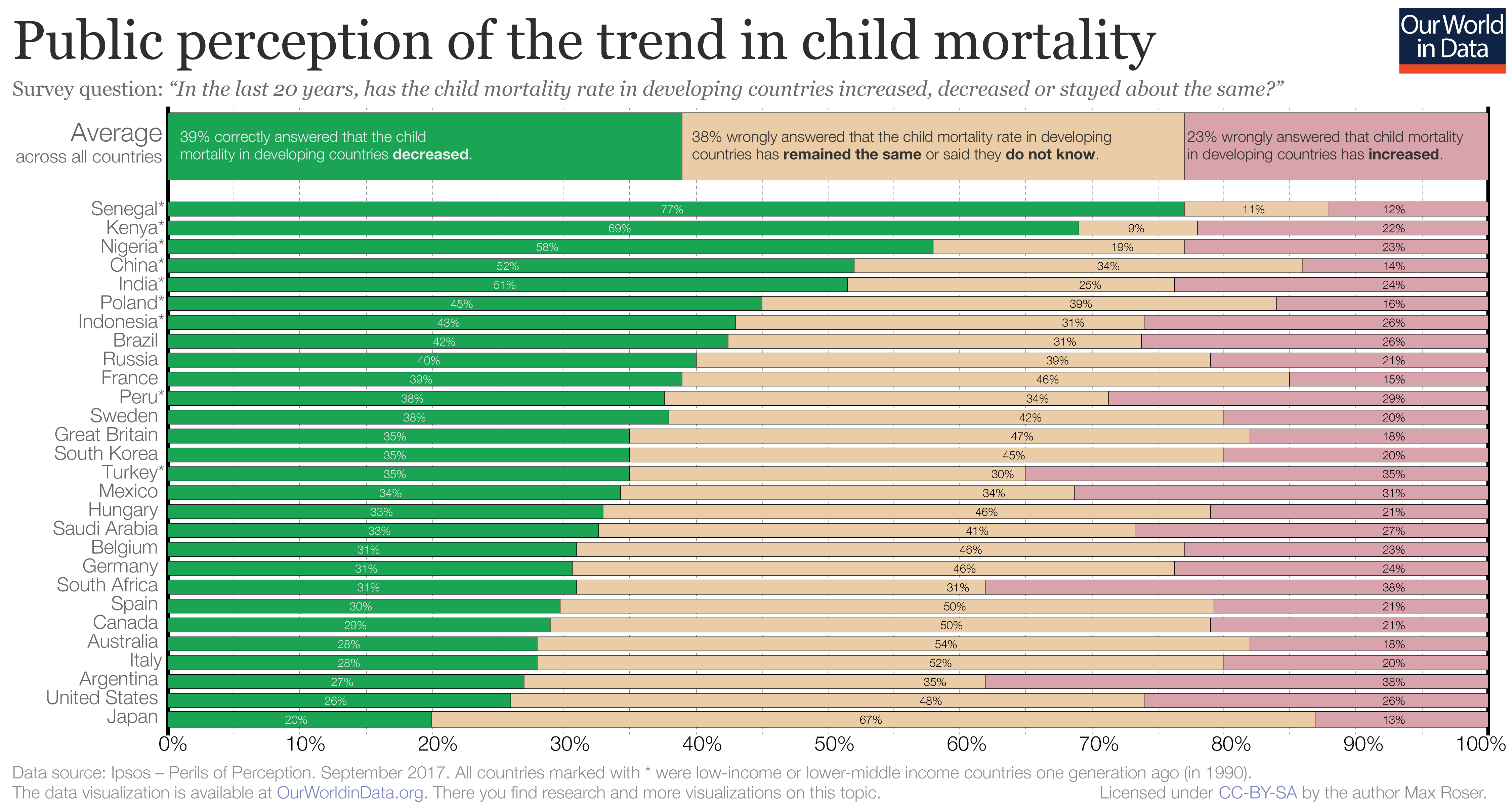

Roser notes,

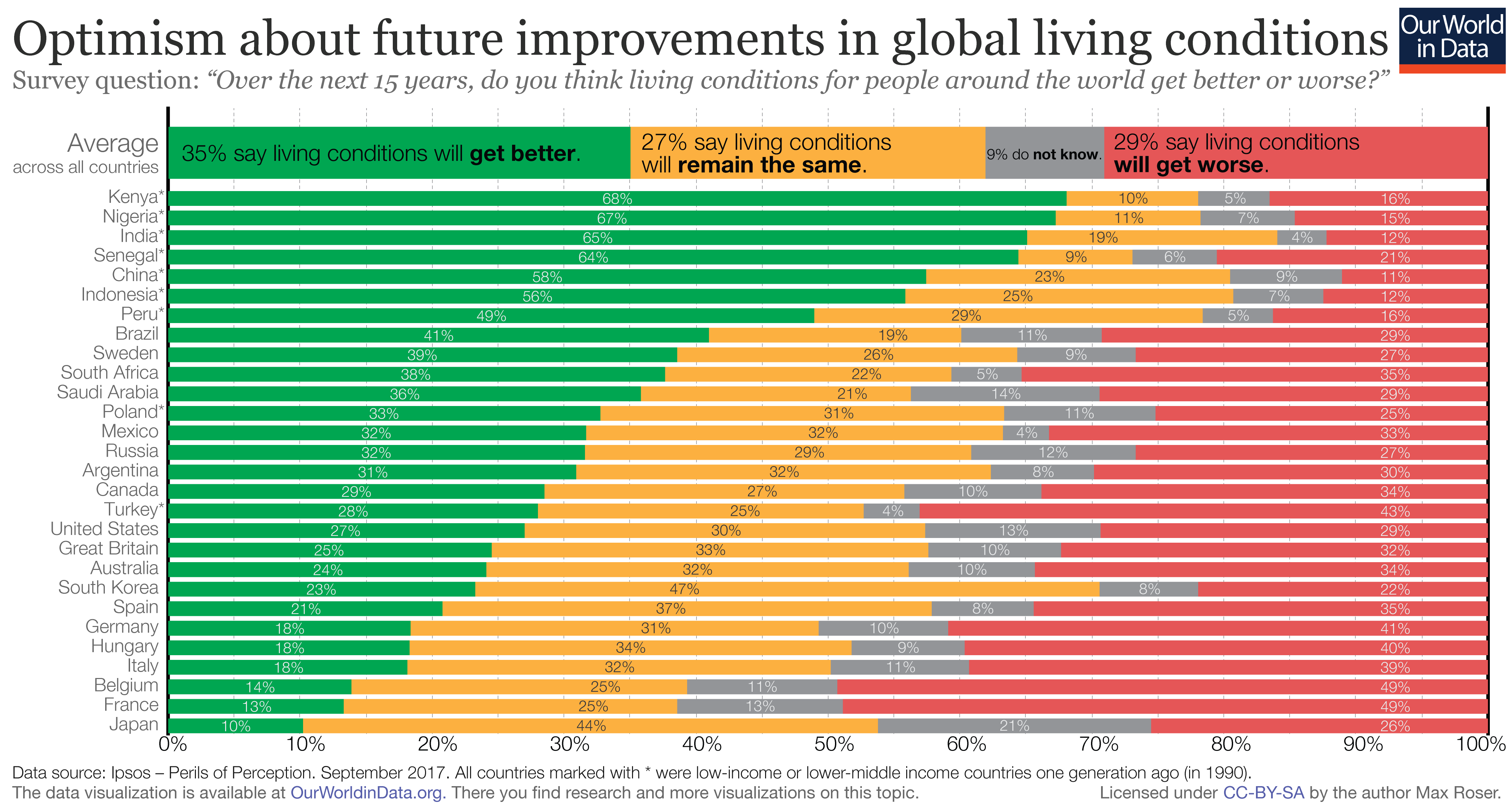

The countries I marked with a star are those that were a low-income or lower-middle-income countries a generation ago (in 1990). In these poorer countries more people understand how global poverty has changed. People in richer countries on the other hand – in which the majority of the population escaped extreme poverty some generations ago – have a very wrong perception about what is happening to global poverty…And just as with knowledge about extreme poverty, the share of uninformed people [regarding child mortality] is much higher in the rich countries of the world…The widespread ignorance about these truly important changes in the world feeds into a general discontent about how the world is changing. When YouGov asked in a separate survey the more general question: “All things considered, do you think the world is getting better or worse?” there were very few who gave a positive answer. In France and Australia only 3%(!) think the world is getting better. And again we see that in poorer countries the share of people who answer positively is higher.

…Finally the survey suggests that there is a connection between our perception of the past and our hope for the future. The chart below shows that the degree of optimism about the future differs hugely by the level of people’s knowledge about global development. Those that were most pessimistic about the future tended to have the least basic knowledge on how the world has changed. Of those who could not give a single correct answer to the survey questions, only 17% expect the world to be better off in the future. At the other end of the spectrum, those who had very good knowledge about how the world has changed were the most optimistic about the changes that we can achieve in the next 15 years…Of course no one can know how the future turns out and there is nothing that would make the progress we have seen in recent decades continue inevitably and not every global development pessimist is ill-informed. But what we do know from these surveys is that these two views go together: Those who are pessimistic are much more likely to have little understanding about what is happening in the world.