This is part of the Stuff I Say at School series.

I started my MA program in Government at John Hopkins University this past month. Homework is therefore going to take up a lot of my time and cut into my blogging. Instead of admitting defeat, I’ve decided to share excerpts from various assignments in a kind of series. I was inspired by the Twitter feed “Sh*t My Dad Says.” While “Sh*t I Say at School” is a funnier title, I’ll go the less vulgar route and name it “Stuff I Say at School.” Some of this material will be familiar to DR readers, but presenting it in a new context will hopefully keep it fresh. So without further ado, let’s dive in.

The Assignment

A recent Pew study showed that millennials are less religiously affiliated than any other previous cohort of Americans (sometimes called the rise of the “nones”). Given the emphasis Tocqueville places on the role religion plays in creating a culture that helps to keep democracy in America anchored, analyze these developments through Tocqueville’s viewpoint[.]

The Stuff I Said

Tocqueville would likely have a strong affinity for Baylor sociologist Rodney Stark’s research on religion. Stark’s sociological analysis of religion takes a similar approach to Tocqueville, acknowledging that the religious competition and pluralism (i.e., religious free market) that resulted from religion’s uncoupling from the state produces a robust, dynamic religious environment. He puts it bluntly in his book The Triumph of Faith: “the more religious competition there is within a society, the higher the overall level of individual participation” (pg. 56). It is the state sponsorship of churches, he claims, that has contributed to Europe’s religious decline.

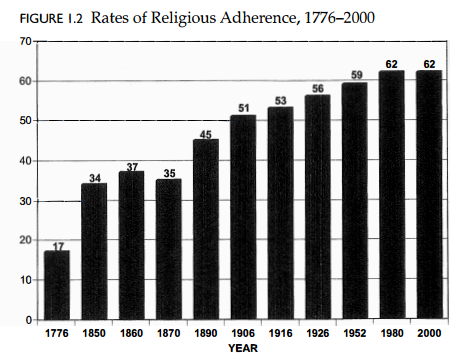

I was struck by the claim in the lecture that 95% of Americans attended church weekly in the mid 19th-century because it contradicts the data collected by Stark and Finke:

On the eve of the Revolution only about 17 percent of Americans were churched. By the start of the Civil War this proportion had risen dramatically, to 37 percent. The immense dislocations of the war caused a serious decline in adherence in the South, which is reflected in the overall decline to 35 percent in the 1870 census. The rate then began to rise once more, and by 1906 slightly more than half of the U.S. population was churched. Adherence rates reached 56 percent by 1926. Since then the rate has been rather stable although inching upwards. By 1980 church adherence was about 62 percent (pg. 22).

Tocqueville might also be more optimistic about the state of America’s religious pulse. For example, Stark has criticized the narrative that often accompanies the “rise of the nones”:

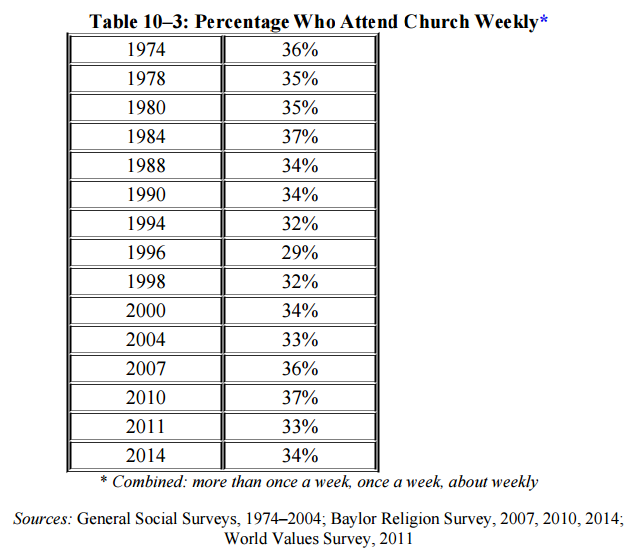

The [Pew] findings would seem to be clear: the number of Americans who say their religious affiliation is “none” has increased from about 8 percent in 1990 to about 22 percent in 2014. But what this means is not so obvious, for, during this same period, church attendance did not decline and the number of atheists did not increase. Indeed, the percentage of atheists in America has stayed steady at about 4 percent since a question about belief in God was first asked in 1944. In addition, except for atheists, most of the other “nones” are religious in the sense that they pray (some pray very often) and believe in angels, in heaven, and even in ghosts. Some are also rather deeply involved in “New Age” mysticisms.

So who are these “nones,” and why is their number increasing–if it is? Back in 1990 most Americans who seldom or never attended church still claimed a religious affiliation when asked to do so. Today, when asked their religious preference, instead of saying Methodist or Catholic, now a larger proportion of nonattenders say “none,” by which most seem to mean “no actual membership.” The entire change has taken place within the nonattending group, and the nonattending group has not grown.

In other words, this change marks a decrease only in nominal affiliation, not an increase in irreligion. So whatever else it may reflect, the change does not support claims for increased secularization, let alone a decrease in the number of Christians. It may not even reflect an increase in those who say they are “nones.” The reason has to do with response rates and the accuracy of surveys (pg. 190).

Finally, Tocqueville was right to recognize the benefits of religion to society. As laid out by Stark in his America’s Blessings (pg. 4-5),the religious compared to irreligious Americans are:

- Less likely to commit crimes.

- More likely to contribute to contribute to charities, volunteer their time, and be active in civic affairs (a recent Pew study provides support for this last one).

- Happier, less neurotic, less likely to commit suicide.

- Living longer.

- More likely to marry, stay married, have children, and be more satisfied in their marriage.

- Less likely to abuse their spouse or children.

- Less likely to cheat on their spouse.

- Performing better on standardized tests.

- More successful in their careers.

- Less likely to drop out of school.

- More likely to consume “high culture.”

- Less likely to believe in occult and paranormal phenomena (e.g., Bigfoot, UFOs).

Overall, I think Tocqueville would be pleased to see data back up his observations.

More Stuff

A classmate pointed to a recent study claiming that when one controls for social desirability, the amount of atheists in America possibly rises to over a quarter of the population. The study is certainly interesting, though I wonder if this would hold up in other countries. Based on Stark’s The Triumph of Faith, these are the following average percentages of atheists across the world:

- Latin America: 2.5%

- Western Europe: 6.7%

- Eastern Europe: 4.6%

- Islamic Nations: 1.1%

- Sub-Saharan Africa: 0.7%

- Asia: 11.3%

- Other (Australia, Canada, Iceland, New Zealand): 8.4%

As for the unaffiliated Millennials, unchurched and irreligious are two different things. A Pew study from last year found that 72% of the “nones” believe in some kind of higher power, with 17% believing in the “God of the Bible.” Even 67% of self-identified agnostics believe in a higher power, with 3% believing in the “God of the Bible.” But unchurching can lead to other forms of spirituality. The Baylor Religion Survey has found, perhaps surprisingly to some, that traditional forms of religion and high church attendance have strong negative effects on belief in the occult and paranormal. In other words, a regular church-goer is less likely than a non-attendee to believe things like Atlantis, haunted houses, UFOs, mediums, New Age movements, alternative medicine, etc. This is probably why Millennials are turning to things like astrology, alternative medicine, healing crystals, and the like.